Navigating Voluntary Administration: The Financial Turnaround of Clenton’s Transport

Table of contents:

- Executive summary

- Background of Clenton’s Transport

- Rapid growth in the business causes insolvency

- Why select voluntary administration to rescue the business?

- The proposal offers a $200,000 contribution by the owner

- How the numbers stacked up: DOCA versus Liquidation scenarios

- Rescue of the business through the DOCA

- Takeaways for transport companies facing insolvency

Executive summary

This study examines a passionate business owner who risked everything to restructure their company through voluntary administration. The company successfully restructured through a deed of company arrangement, saving the business.

This case study explores a well-run business that struggled with the financial strain of rapid growth. Prevention is better than cure and if a business is going through rapid growth the business owner needs to ensure that the business has sufficient working capital.

The ATO supported the restructure, resulting in unsecured creditors receiving 28 cents on the dollar. That result is well above average for restructures of insolvent companies in Australia and this case study is useful for owners of insolvent transport companies.

Background of Clenton’s Transport

Clenton’s Transport was founded in 2009, with Mr. Clenton as its sole director and owner. Up until its restructure, the business was called Clenton’s Transport Pty Ltd (the Company).

The director of the Company is a passionate businessman who was committed to the transport industry.

The business specialized in transporting shipping containers. It obtained approval from the National Heavy Vehicle Regulator to use 85-tonne GCM 30-metre A-doubles to move shipping containers from Port Botany to Sydney’s west. Transporting multiple shipping containers simultaneously increased efficiency.

Rapid growth in the business causes insolvency

A business without debt cannot become insolvent. For example, BHP Group Limited maintains a low ratio of debt to assets and income, ensuring financial stability. It is a company that is in a very strong financial position. This means its liquidity risk is very low and therefore very unlikely to go into bankruptcy.

Small-to-medium sized businesses aren’t usually able to build up the same financial moat that BHP has built up. They need to build businesses with sweat capital and debt. In the transport industry it is normal for businesses to have their entire fleet financed and if cash flow is tight to also finance their receivables to ensure they can meet immediate obligations (such as payroll). The Company’s principal assets were the sweat capital of the director and its fleet of trucks and trailers. The fleet of trucks and trailers was valued at $3-4m and it was completely financed by secured creditors.

The post-COVID period was not a good period for the transport industry. It suffered from the after effects of the COVID-era government stimulus, including increased costs and difficulties in passing those costs onto customers.

The problem that Clenton’s Transport had was that it grew too fast and as business growth costs money (in working capital) it faced insolvency. Unlike BHP small-to-medium sized businesses don’t have professional accountants inhouse to manage growth and they often miss out on necessary professional advice.

One symptom of tight cash flow is that rather than drawing a salary the business owner draws out cash by way of loan. This means that the incidence of personal taxation is deferred but the owner can still pay themselves. To minimise tax the director took out a loan rather than drawing wages for those amounts. By the time of the restructure this had gone up to $1.628m and it was unsustainable – paying it out as a salary would have resulted in a big tax bill for the director that he couldn’t pay.

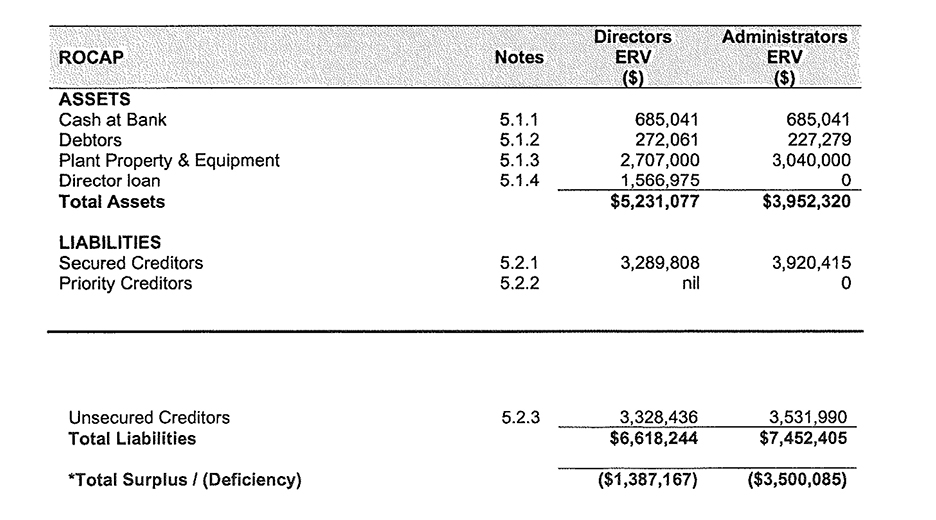

When the Company went into voluntary administration it was in a negative asset position. It had a good cash position, but it faced a $3.5m asset deficiency overall:

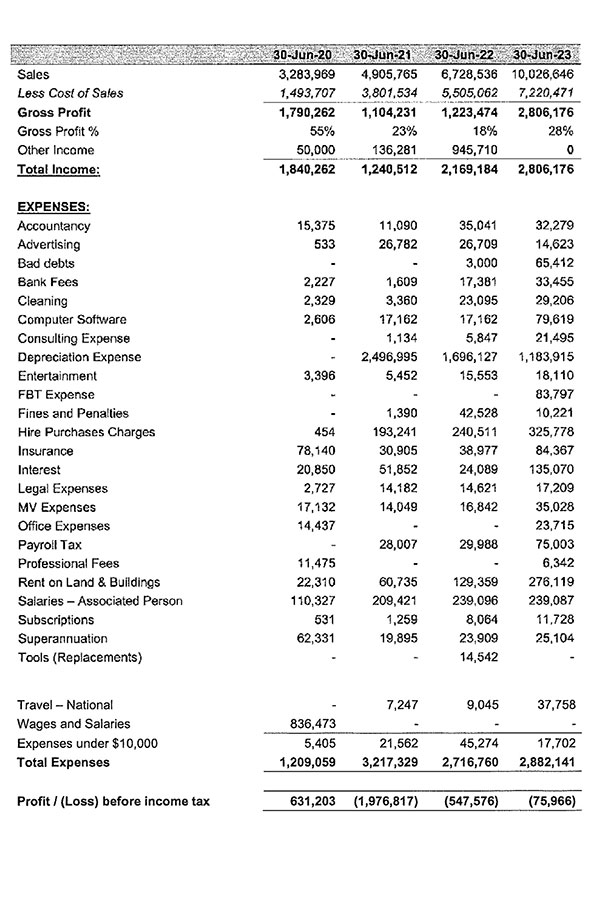

What was the cause of this deterioration? It was driven by rapid growth of the business between 2020 and 2023. The growth was so strong that the director’s sweat capital and debt finance weren’t enough to sustain it. The Company had gone from $3.2m in sales in 2020 to $10m in 2023.

The company generated a healthy profit of $631,203, a strong figure for a single-owner business. But that healthy profit in 2020 turned into a disastrous loss of $1,976,817 in 2021 and $547,576 in 2022. The cash-flow effects of the losses weren’t terminal because when you add back depreciation as a non-cash expense the business was cash flow positive, but the growth came at the cost of profitability. The growth was not managed, and the Company could have avoided a voluntary administration through controlled growth.

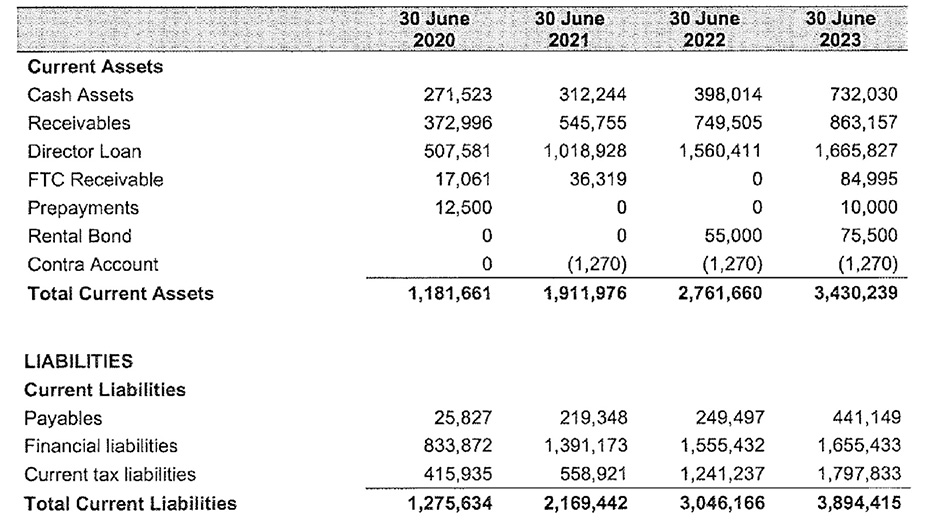

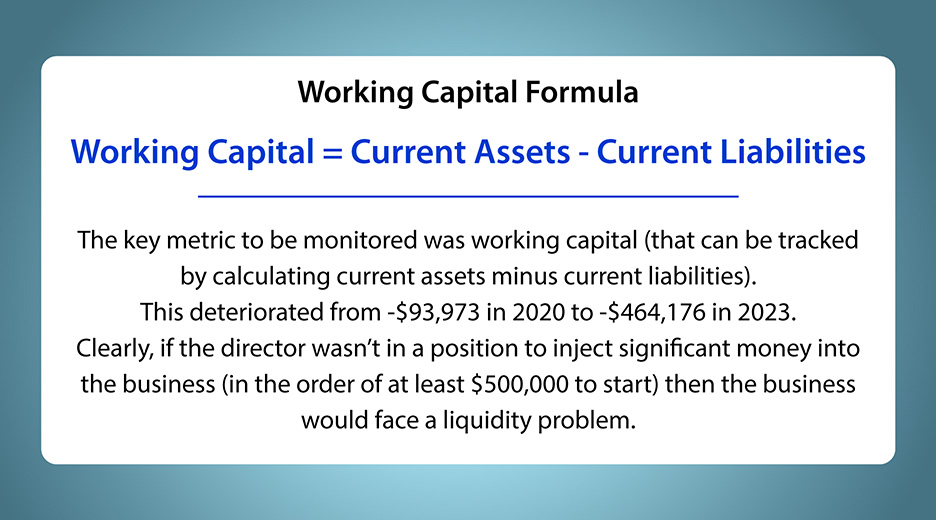

The key metric to be monitored was working capital (that can be tracked by calculating current assets minus current liabilities). This deteriorated from -$93,973 in 2020 to -$464,176 in 2023. Clearly, if the director wasn’t in a position to inject significant money into the business (in the order of $500,000) then the business would face a liquidity problem.

Part of the growth strategy included key investments included leasing a large yard for storing shipping containers and this resulted in rent expenses kicking up from $22,000 in 2020 to $276,000 in 2023. The new yard gave the business a competitive advantage because it meant that they could store shipping containers in Sydney.

While the business grew its balance sheet deteriorated. In 2020 its net asset position (total assets minus total liabilities) was -$875,745 and by 2023 it was -$3,591,106. For a small-to-medium sized business this is not a sustainable financial position.

During the COVID pandemic the ATO held back on calling in tax debts as part of the national hibernation strategy. Because tax debt payments were delayed this caused a backlog in company external administrations that then played out in 2023 and 2024. The Company is a case in point. Its current tax liabilities (above current liabilities table) increased from $415,935 in 2020 to $1,797,833 in 2023. Any experienced insolvency professional would recognise that as soon as the ATO took action to call in its debt the Company would need either a significant injection of capital or to go into external administration. The third option of entering an instalments plan with the ATO was a possibility but if the ATO required the debt to be paid off within 18 months it was clear that the business did not have $100,000 / month in free cash flow that would have been required.

Pre-appointment work is undertaken

When a business faces a liquidity crisis the first response should be stabilisation. That could involve the following actions:

- Obtaining further working capital

- Renegotiating trading terms with suppliers

- Negotiating instalment arrangement with the ATO

Following stabilisation action to downsize a business are the next steps in typical responses to a liquidity crisis. That could involve the following action:

- Terminate contracts and employees

- Sell assets

- Develop and implement management objectives

One critical step the business took was to sell excess equipment with the objective of reducing equipment financing costs. Over the course of 2023 the business sold trucks and trailers, and this had the dual effect of reducing debt (by repaying secured creditors) and if there was a surplus on sale to obtain further working capital.

By April 2023 the director was meeting with professional advisers and insolvency practitioners and seriously considering the voluntary administration process. This involved educating the director about insolvent trading and director penalty notices and helping them to develop a strategy.

When a business starts it is typical that directors set up a simple structure that is run through one entity. Over time this structure does not give the director (and their family) satisfactory asset protection and so it is revised. Using a single entity for a business structure is analogous to putting all your eggs in one basket. It is typical that at some time directors of small-to-medium enterprises create an optimal business structure through new contracts, companies and/or trusts. In anticipation of external administration, the Company changed its name from Clenton’s Transport Pty Ltd to JGC Investment Holdings Pty Ltd in September of 2023. The director also created another company called Clenton’s Transport NSW Pty Ltd – which we will refer to as the Newco. The Newco was created in July of 2023 and the change of name of the Company (from Clenton’s Transport Pty Ltd to JGC Investment Holdings Pty Ltd) somewhat dissociated the Company from the Clenton’s brand. This was linked to the transaction to transfer business assets set out below.

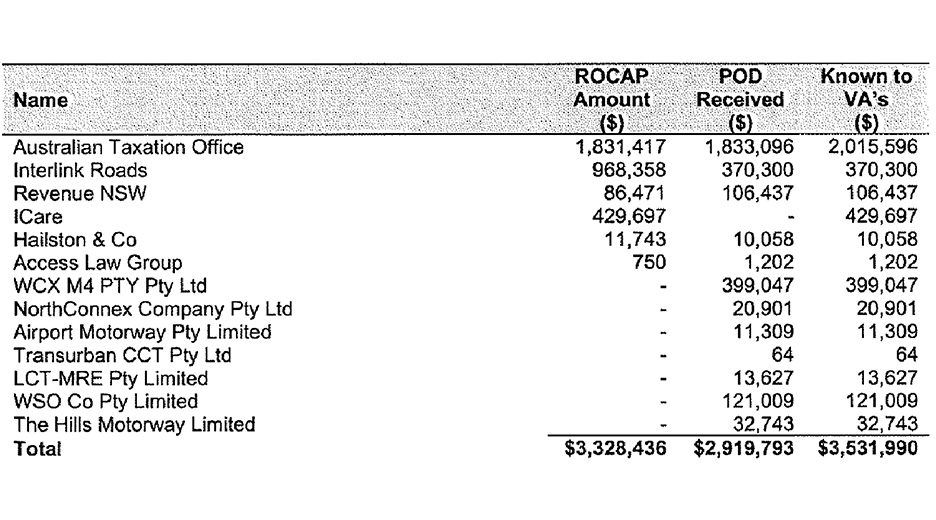

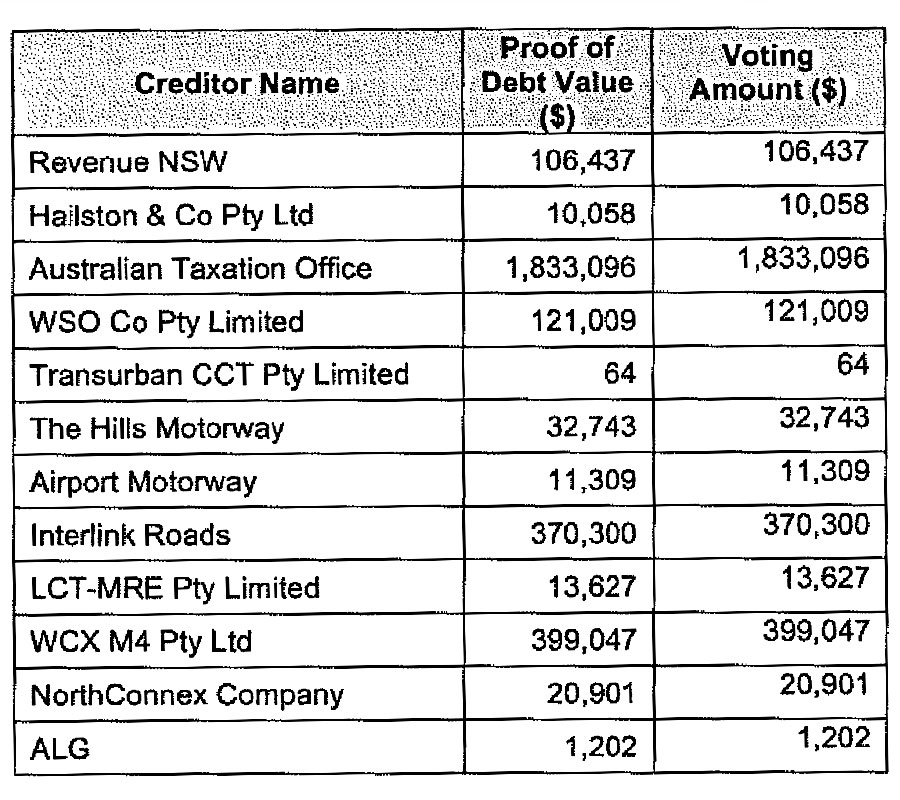

By the time the Company went into voluntary administration it only had 13 unsecured creditors. This involved managing unsecured creditors by transferring employees to the Newco and paying off smaller creditors in the course of business and transferring ongoing obligations to the Newco. The list of creditors is below and it included mostly statutory creditors and corporates – but no ‘mum and dad subcontractors’:

An illegal phoenix is broadly a transaction that occurs to transfer business assets from an insolvent company to a newco for inadequate consideration. That is a pretty rough definition, but it is illegal in Australia and liquidators have a variety of powers to obtain compensation for creditors for illegal phoenix activity. The director obtained a business valuation report to assess the value of the assets of the business and the report found that the business itself had no value. This is typical for insolvent companies where the fire sale value is the breakup value of the business. In this case it was the auction value of the plant and equipment that is not subject to a security interest.

Before the Company was put into voluntary administration it entered into a business sale agreement to transfer business assets and liabilities to the Newco. The Business Sale Agreement (BSA) had the following terms:

- Condition precedent it is approved in the DOCA and if not approved it terminates

- Transfers all employees including current and future entitlements to the newco ($148,978)

- Consideration paid $4

- Business known as Clenton’s Transport to be transferred consisting of the following assets:

- Plant & Equipment (not subject to security interests)

- Intellectual property

- Stock

- Goodwill

- The transaction excluded plant & equipment (including trucks and trailers) that was subject to security interests

- The Newco could pay any liability of the Company it chose

- Newco had agency to collect debtors of the Company

There was also a second agreement entered into called the ‘Dry Hire Agreement’. In consideration for a fee of $83,000 plus GST the Company hired all the plant and equipment (that was not part of the BSA above). This mean that all the trucks and trailers that were subject to security interests were able to be utilised by the Newco. It would have been very unlikely that all the secured creditors would have agreed to the transfer of the trucks and trailers from the Company to the Newco.

What allowed the BSA to take place was that no creditor had an All-PAAP. If the Company had entered into a general security agreement with any one creditor and granted an all present and after-acquired security interest to that creditor it would have been necessary to obtain consent for the BSA.

The Company also followed the tactic of saving as much cash as possible. At the date of the appointment of voluntary administrators the Company had saved the amount of $685,041. This indicated how seriously the director approached the voluntary administration process and ensuring that it was fair dinkum. It is unfortunate that most external administrations in Australia start with zero cash at bank. This means that there is also zero chance of restructure through the external administration procedure (be it voluntary administration or another process).

Why select voluntary administration to rescue the business?

Like most small-to-medium sized businesses the Company’s economic engine was based upon debt financing and the sweat capital of the owner-operator. Before the restructuring, the company’s largest assets—trucks and trailers valued at $3-4 million—were fully financed. Therefore, in the event of a liquidation of the Company the unsecured creditors would have taken a severe haircut. All the secured financiers (for the trucks and trailers) were different for each vehicle so, from the technical view of an insolvency lawyer, that would make it very difficult to gain a consensus from those creditors.

It is a sad reality, but it is more straightforward to restructure a large corporate than a small-to-medium sized business because the large corporate may have a single financier that dominates their balance sheet liabilities. It is typically very difficult for an SME transport company that faces insolvency to restructure using the voluntary administration procedure because of a spread of creditors.

Australia’s small business restructuring process has a high success rate. However, Clenton’s Transport exceeded the $1 million debt threshold, making it ineligible. The voluntary administration procedure was the only available restructure procedure for the Company.

The Company undertook some pre-positioning before commencing the voluntary administration process but this was not a pre-pack insolvency arrangement. Pre-pack insolvency arrangements involve substantially transferring all of the necessary assets of an insolvent company out of that company and into a new company. This wasn’t an option for Clenton’s Transport for a couple of reasons. The first reason was that all the trucks and trailers were subject to security interests and it wasn’t feasible to obtain the consent of all the financiers to transfer the equipment out of the Company into a Newco. The second reason was that there was a chance of severe blowback from creditors. In a pre-pack scenario, the assets of the Company would be transferred out of the Company and paid for based upon an independent valuation. However, when a company is insolvent the valuation is usually based upon the breakup value of the business not a valuation as a going concern. An insolvent company can’t be valued based upon a multiple of maintainable earnings because that isn’t possible to project when a company is losing money. The result is that the consideration that is ultimately paid by the Newco to the insolvent company isn’t sufficient to cover all the creditors. There is likely to be some bad blood with creditors and damage to the reputation of company directors as a result of pre-packs. It is likely that an incoming liquidator and creditors (such as the ATO) will classify their actions as phoenix activity even if there is no legal claim that is maintainable against the directors (i.e they haven’t done anything illegal).

The Company was put into voluntary administration by its sole director in October of 2023. The restructure procedure for a voluntary administration is that following a proposal by directors the proposal is voted upon by creditors. If the creditors approve of the director’s proposal the parties sign a Deed of Company Arrangement (DOCA).

There is nothing in the law of voluntary administration that requires the voluntary administrator to continue to trade. There is a strong incentive against trading in circumstances where a company is not cash flow positive. This is because the voluntary administrator is personally liable for any shortfall in trading receipts. So, the result is that the insolvency practitioner who is appointed as the voluntary administration is not going to take any personal risks.

The other risk for the directors during a voluntary administration is that business assets may be sold by the voluntary administrators. There is no legal requirement for voluntary administrators to hold onto business assets until creditors can consider the directors’ DOCA proposal to restructure the company’s debts.

Should the director’s DOCA proposal go through to a creditor vote to succeed it is necessary for both the majority in value and the majority in number of creditors to vote in favour of the proposal. There is a fallback where the voluntary administrators have a “casting vote” in the event of a deadlock but this isn’t something that comes up very much in practice. Insolvency practitioners would understandability be conservative in exercising their casting vote and it would be likely to align to their overall opinion about whether the DOCA proposal is in the best interests of creditors.

The proposal offers a $200,000 contribution by the owner

The analysis of DOCA proposals focuses on comparing the director’s proposal to a liquidation scenario. That is, if the DOCA proposal was not accepted and the company was placed into liquidation the amount of return that creditors would receive.

It is fair to say that the proposal to creditors in this case study was at the lower end. The proposal required the director to contribute $200,000 of personal funds.

The rationale of the voluntary administration procedure is that it should firstly be used to save insolvent businesses and if that isn’t possible to ensure the best possible returns to creditors. This means that the legislators intended for the directors to have a decent opportunity to restructure before their insolvent company was put into liquidation. Any DOCA proposal must give creditors a commercial basis to accept a compromise and this usually involves a deed contribution of upfront cash from the director’s pocket plus some receipts from future trading.

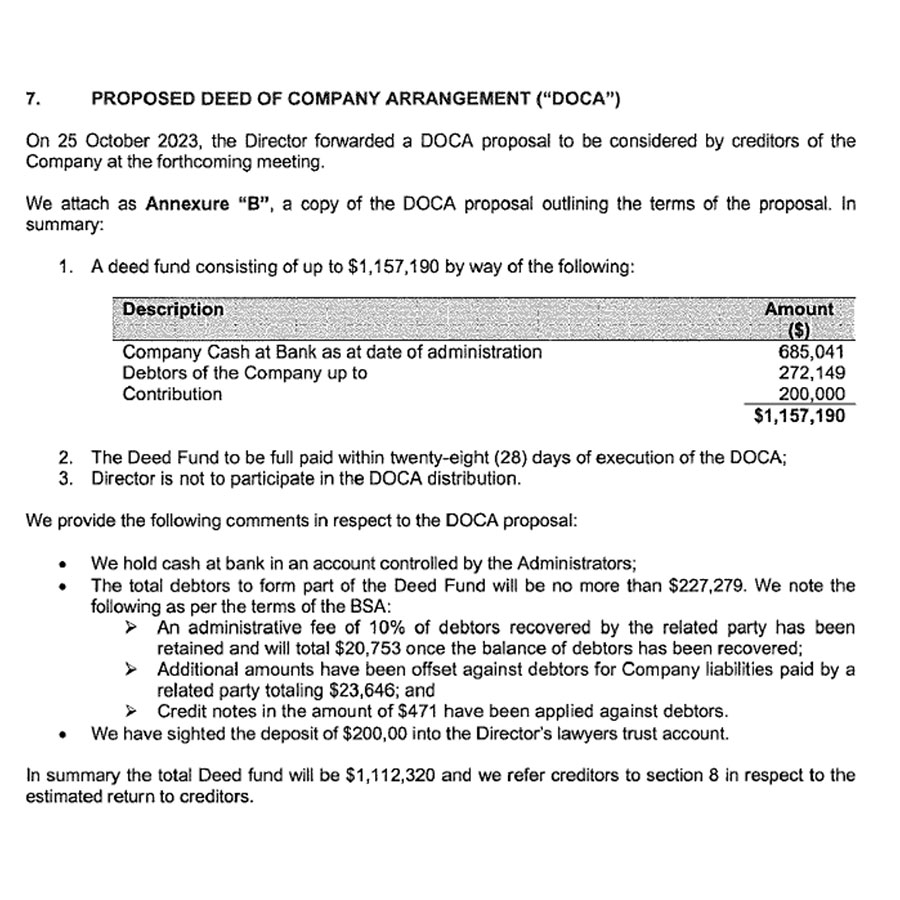

The proposal that the director of Clenton’s Transport put to creditors was that he would offer $200,000 on top of most of the unsecured assets that creditors would have been entitled to in a liquidation scenario. The unsecured assets were the unpaid debtors and cash-at-bank. The voluntary administrator’s description of the proposal is set out below:

The headline figure of the proposal is that creditors would get a part of a deed fund of $1,112,320. It is worth noting that the loan to the sole director of $1.628m was not part of the deed fund.

We explore below how this proposal was analysed by the voluntary administrators and how accepting this proposal would compare to a liquidation scenario.

How the numbers stacked up: DOCA versus Liquidation scenarios

Voluntary administrators are required to give a professional opinion about whether it is in the interests of creditors to accept a DOCA proposal.

The administrators analysed the pre-positioning transactions undertaken by the director (set out above). The administrators formed the view that the Dry Hire Agreement (involving a monthly payment of $83,000 to hire trucks and equipment) was reasonable. But they found that the Business Sale Agreement was not satisfactory and that it could be a voidable transaction. A voidable transaction is a transaction that a company liquidator would look at reversing (i.e. clawing back for creditors). The concern with the Business Sale Agreement was that it undervalued the assets that were transferred. On the other hand, the director had obtained a professionally prepared business valuation in support of their valuation. Further, in consideration for the transfer the Newco took on $148,000 in employee liabilities from the Company.

Having kept their options open in the event of a liquidation to claw-back assets the voluntary administrators nevertheless recommended that the DOCA proposal be approved by creditors. To explain why they recommended acceptance by creditors we will discuss their work process, assumptions and calculations below.

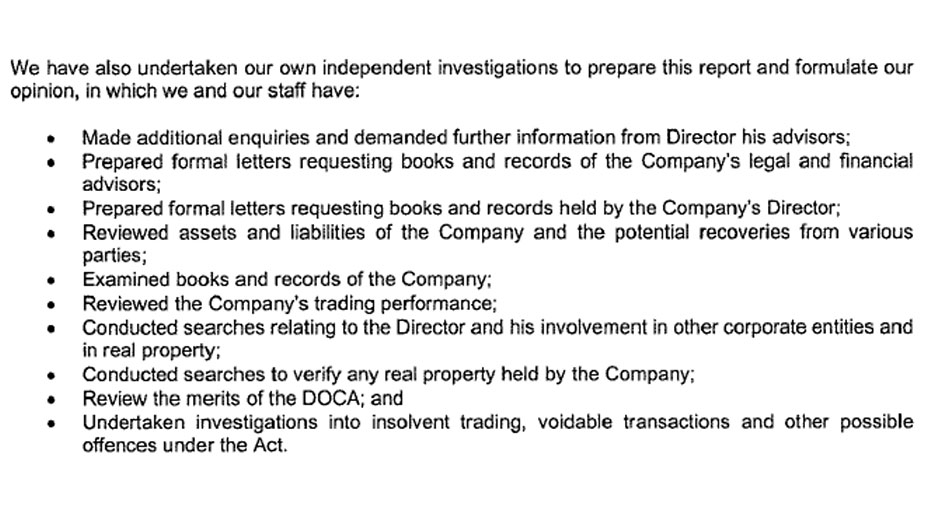

The voluntary administration procedure is relatively short and so one of the complaints that insolvency practitioners have is that they have insufficient time to properly investigate the affairs of companies before they are required to report to creditors. In our experience they get most of what they need done. The basic work undertaken by the voluntary administrators in this matter was typical. It involved ensuring that the company trade was cash flow positive and that the balance sheet assets were verified. Set out below is the table describing the professional work undertaken:

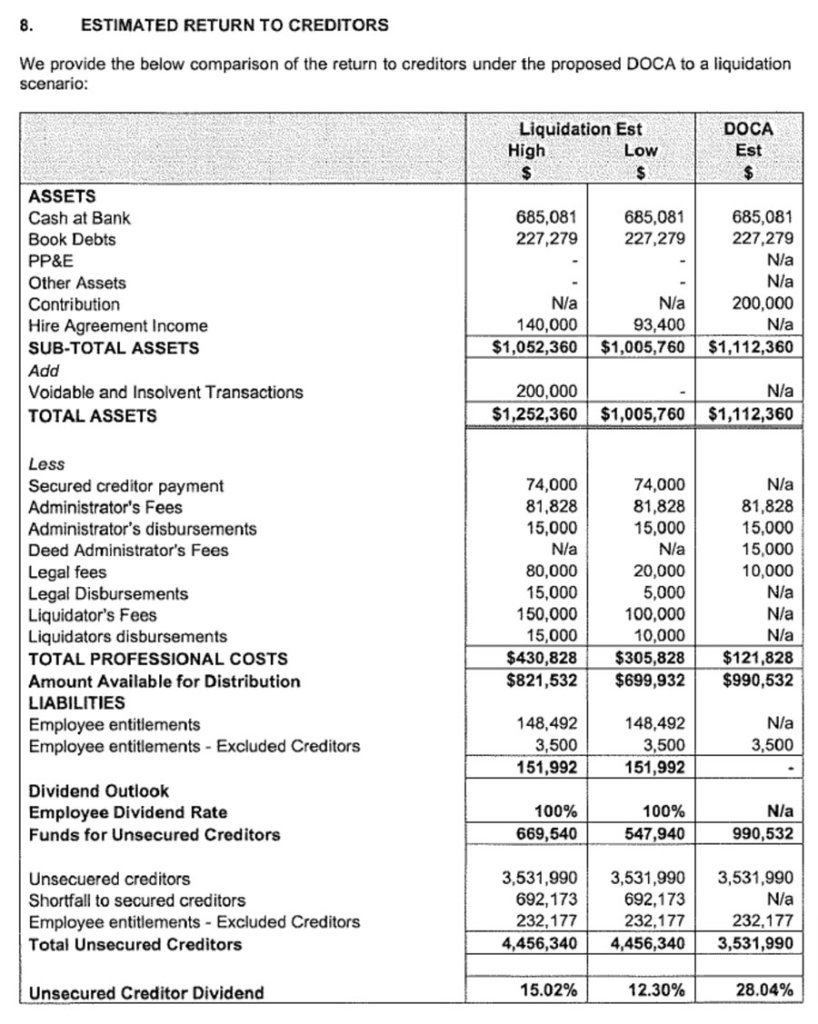

The creditors reading the administrator’s report will be interested in the bottom line, that is the amount of a dividend they would receive. The voluntary administrator’s analysis was that creditors would receive 28c in the dollar through a DOCA versus in liquidation versus 12-15c in the dollar through a liquidation.

The key creditor in the external administration was the ATO (owed at least $1,831,417). This is usually the case in small-to-medium sized external administrations. One issue peculiar to the ATO for this matter was that if the ATO voted against the DOCA proposal it could also have faced a claw-back action for preferential payments. The voluntary administrators found that in a liquidation scenario a liquidator (i.e. them) may have the right to claw back unfairly preferential payments that the Company made to the ATO (in the 6 months before the voluntary administration commenced). It is useful to note that the voluntary administrators found that in the liquidation scenario that a $217,000 unfair preference claim could be made against the ATO for the rounded payments the Company made to the ATO in the 6 months before the voluntary administration started. This is a red flag for the ATO but, in our experience, however, the calculation of loss by the ATO is not the primary basis of whether the ATO will support a DOCA. The ATO does not want to support a “dodgy” DOCA, that is, a DOCA that is unrealistic, doesn’t make commercial sense or rests on inadequate disclosure. In this matter the voluntary administrators found the company kept proper books and records and the reporting to creditors was properly detailed. There is no exact science to predicting whether the ATO will support a DOCA proposal but if there is proper compliance, a real business with a track record and a proposal that makes commercial sense this could be enough to get ATO support.

Another key decision made by the voluntary administrators was their finding that the director’s financial position meant that he would be unable to repay the director’s loan and that any other claim against him (such as an insolvent trading claim) was unrecoverable. This opinion was largely based on a statutory declaration and independent analysis undertaken by the voluntary administrators. Like many directors of small-to-medium sized enterprises their net worth is tied up with their business. This is a key finding because it supported the low figures of the liquidation scenario and the proposition that obtain recovery through a DOCA (rather than bankrupting the director) would put the creditors in a better financial decision.

Below are the detailed calculations that the voluntary administrators provided to creditors to support their conclusion that accepting the DOCA proposal was in their best interests.

A DOCA return of 28c in the dollar to unsecured creditors was well above average. One empirical review found that the weighted average return of a sample of DOCAs was 9.7c in the dollar (Wellard 2013). There is no readily accepted minimum for DOCA returns (i.e. a rule of thumb) that experienced creditors (such as the ATO) will apply.

The transfer of the funds to the deed fund would then put the director of the Company in a position of requiring working capital to fund the ongoing operations of the Newco. A sensible company director would do a cash flow forecast to work out the minimum level of working capital that is required to fund the business after the DOCA is approved and the company is handed back to the director. From that date the director will need to pay rent, wages and other overheads to maintain business operations.

Rescue of the business through the DOCA

The purpose of the second meeting of creditors is to decide the future of the company. Either the company gets restructured (through a positive vote in favour of the DOCA proposal) or it goes into liquidation. The result is in hands of the creditors. Sometimes there are fireworks at these meetings but generally creditors have made up their minds about voting in advance of the meeting (based upon the creditors report and their discussions with the voluntary administrators) so meetings are usually just procedural affairs.

The voting regime requires that a majority in value and majority in number of creditors vote in favour of the DOCA proposal for it to succeed. There is a backup of a casting vote for the voluntary administrators where there is a deadlock but that was not relevant in this matter.

There were a relatively small number of creditors for this administration and the creditors were largely either statutory (i.e. the ATO) or corporate (e.g. motorway operators). That meant that the smaller creditors and subcontractors were paid in the ordinary course of business through the Newco. It is also noteworthy that no employees or subcontractors were voting as they had been transferred to the Newco.

On the day of the vote there were creditors totalling $2,919,793 admitted to vote. Of those creditors the ATO held the majority by value ($1,833,096). The following creditors lined up for the vote about the DOCA proposal:

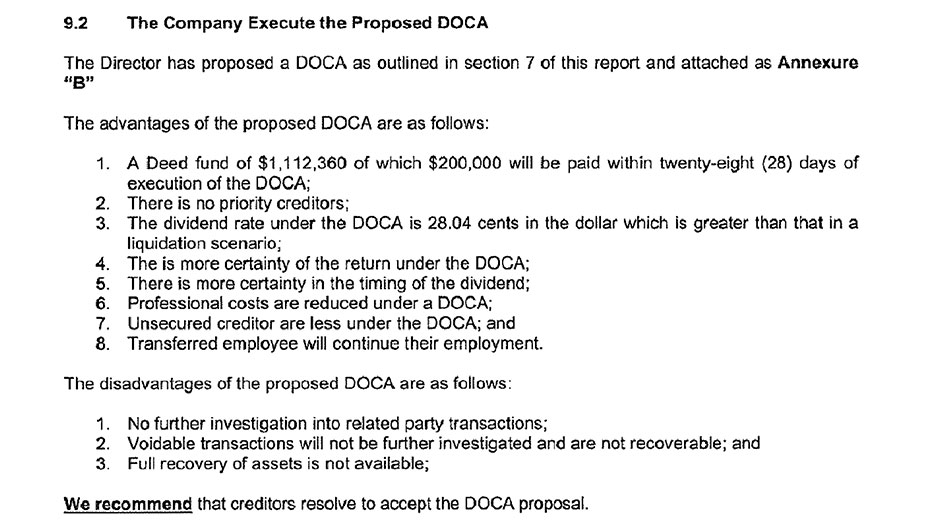

The arguments in favour of the DOCA were summarised in the creditors report:

The result of the second meeting of creditors in November of 2023 was that the creditors followed the recommendation of the voluntary administrators and voted to approve the DOCA. The vote was unanimous. It was the result of professionalism by the voluntary administrators, a sincerely dedicated businessman running Clenton’s Transport and a sensible restructure proposal that gave creditors a decent return.

In January of 2024 the whole process concluded with the termination of the DOCA. This mean that the DOCA had achieved its purpose and the compromise arrangement with creditors was completed. In this case the $200,000 deed fund contribution was paid out and the debtors collected.

Takeaways for transport companies facing insolvency

Successful restructures of insolvent transport companies are rare in Australia. More commonly, these businesses undergo asset liquidation and closure. The causes of insolvency in the transport industry are low barriers to entry and high competition, significant financing costs, locked-in contracts restricting price increases, poor strategy and poor financial controls.

The voluntary administrators of Clenton’s Transport found that the company had been trading insolvent for two years before the company was placed into voluntary administration. The ATO’s leniency during the COVID period contributed to a surge in insolvencies once normal enforcement resumed. Prevention is better than cure and better financial management could have avoided a voluntary administration. Growing from $3.2m of sales in FY2020 to $10m of sales in FY2023 was unsustainable and required more working capital than the company had access to.

The other issue is that the business was not well structured. The business traded through a single entity and there was no asset protection strategy in place. Creating a simple business structure that separated the assets and business risk into one entity (such as a trust) that held assets and another entity that traded and carried the business risk would have been a good step in the direction of optimal asset protection.

For the director to put the Company into voluntary administration while there was a directors loan of $1.6m owing was a high risk calculation. If the DOCA proposal had failed the liquidator would have called in the loan and the director would have personally become insolvent. If no negotiated outcome could be sorted out with the liquidator the director may have gone into personal bankruptcy.

Through the voluntary administration process the director put his business in the hands of the creditors. The key creditor in this scenario was certainly the ATO. The creditors had comfort through a properly run administration and obvious propriety of the director to give their support to the DOCA proposal.

This is a case study where the good guys won.