What should a Pre-Insolvency Adviser (a lawyer, accountant or other professional) do to help a financially troubled small or medium-sized business?

Pre-insolvency advisers are professionals who help business owners to conduct a root cause analysis to understand why their business is failing and then help them to develop a turnaround strategy (i.e. what to do next) or if this is not possible, plan an orderly winding up.

Index:

- What is the problem for SMEs?

- Is your business viable?

- If your business is failing, who should you call?

- When should you engage a pre-insolvency adviser?

- How do I know if I am insolvent or on the path to becoming insolvent? The symptoms

- What is a zombie company (and the root causes)?

- What is the turnaround process?

- What do effective pre-insolvency advisers recommend?

- What are common turnaround mistakes? The Survival Trap

- How do I avoid these turnaround mistakes?

- What should I look for in a pre-insolvency adviser?

- What are common mistaken strategies used to respond to financial problems?

- Who are the effective pre-insolvency advisers?

- Who are the terrible insolvency advisers?

- Pre-insolvency crooks in the news

- What should a professional adviser do in a pre-insolvency scenario?

- What financial tools should be used to assess the viability of a business?

- What skills will a good insolvency lawyer have? What are the benefits of engaging one?

- What are the downsides of insolvency lawyers?

- What if only part of the business is viable?

- What do I do next?

“Beware the pre-insolvency advisor bearing promises of financial salvation” – Kate Carnell, Small Business Ombudsman (2019).

“Lots of insolvent SMEs get lost in the insolvency industry. They need to be careful and ensure that any professional adviser they find is ethical and has a high level of experience and knowledge (such as insolvency practitioners and insolvency lawyers). Otherwise it will be the blind leading the blind into financial oblivion.” – Ben Sewell, Sewell & Kettle Lawyers (2020).

What is the problem for SMEs?

SMEs are businesses with less than 200 employees and they constitute 97% of all businesses in Australia according to the Productivity Commission.

The first step for SMEs worried about their financial position is to figure out what the underlying problem is with their business. Directors will note symptoms, such as poor cash flow or losing key customers, but in order to figure out what to do next, they need to identify the underlying causes of these symptoms through analysis.

In the past, lawyers and other insolvency advisers have avoided getting too involved in pre-insolvency scenarios. It is likely that they don’t see their business as helping ‘zombie companies’ and they wait until they are forced to consider a formal insolvency appointment by actual insolvency. The result is that they provide advice too late in the life cycle of struggling SMEs and business owners lose the chance of saving a struggling business. These lawyers and advisers then shunt off their clients to the voluntary administration process, which usually results in a liquidation and then a fire sale of business assets. This gap in the market for pre-insolvency advice has unfortunately been filled by snake oil salesman; a combination of liquidators who have been struck off and shady marketing types who are all talk and no walk. Insolvency lawyers and insolvency practitioners are usually trained as terminators not saviours, and unfortunately there is a culture of looking down on clients and rapacious charging.

Is your business viable?

For many businesses facing insolvency, the question at the forefront of directors’ minds is “can I save the business?” This question rarely has a clear answer. For many SMEs, especially those that are family run and have a long history, the business will be more than just a job – it is a livelihood and their tribe. Other intangible value moves with the proprietors, regardless of what happens to the company structure itself, so there is an opportunity for phoenixing. However, it is important to consider the advice of experts before deciding what to do next; there may be a way to save goodwill value through a restructure, although being decisive and willing to make tough calls is essential to ensure viability is lasting.

Because it is costly for governments and the economy to have high rates of business failure, there exists a body of law to protect contractual rights, wind up companies and, where acceptable, facilitate business restructure. The economic rationale for allowing insolvent businesses to restructure is whether or not the going-concern value is greater than the liquidated value of its assets. If the former is greater than the latter, then restructure is usually encouraged. The going-concern value refers to the ‘total’ value of a business and is different from the liquidated value in that it encapsulates the value derived from the fact that the business is an ongoing operation that has the ability to continue to earn a profit. However, it is often difficult to figure out and place a value on these aspects of a business, which are constantly fluctuating, difficult to quantify and highly subjective. In addition to going-concern value (also known as an asset approach) and liquidated value (slightly below what is known as market value) the ATO identifies income, cost and probabilistic approaches to valuation. Often, several of these approaches may need to be combined to get an accurate idea of value. There is also no way to place an economic value on the goodwill of a business that follows the proprietors – it can’t be captured in a liquidation process in any event.

According to Altman, Hotchkiss and Wang in ‘Corporate Financial Distress, Restructuring and Bankruptcy’, “the efficiency of any bankruptcy system can be judged by its ability to appropriately identify and provide for the restructuring of firms that arguably should be able to survive.” In this regard, it is clear that Australia’s bankruptcy and insolvency regime leaves a lot to be desired, given the documented inability of voluntary administration to save jobs, preserve goodwill value and facilitate a return to trade and the inability of liquidations to secure good returns for creditors. These failings are exacerbated when the process concerns small businesses. There is no difference in the way these formal processes are carried out for large and small businesses, and many advisers are ill-equipped to provide tailored advice specific to industry and size. As such, the insolvency system and the way it is implemented is ill-suited for many businesses. Some companies may be forced into formal processes where there are viable alternatives available, while others may flounder and attempt restructuring at the cost of the business when they are inevitably forced to liquidate.

For SMEs, the viability of a business depends on potential profitability and the energy and working capital that the proprietors are prepared to expend to grow and improve the business. If one of those three essential elements are missing, then the business is not likely to be viable.

‘Distressed restructuring’ refers to fixing failed firms, and requires businesses to conduct either asset restructuring or financial restructuring. Asset restructuring improves operations and cash flow, resulting in greater efficiency. Financial restructuring makes the cost of capital cheaper to attain sustainability through deleveraging. To identify if a struggling business is viable, it is worthwhile for owners (in consultation with a professional adviser) to examine whether either of these types of restructuring may work for them, and whether they might be best achieved through an informal process of business restructure assisted by professional advice, or through a formal appointment.

If your business is failing, who should you call?

Pre-insolvency advisers are professionals who help business owners conduct a root cause analysis to understand why their business is failing and then help them to develop a turnaround strategy (i.e. what to do next) or if this is not possible, plan an orderly winding up. There are a range of different types of pre-insolvency advisers but unfortunately, it is a poorly regulated area. It is important to do your research on the different pre-insolvency advisers before engaging anyone. Avoid snake oil salespeople at all costs – see below in this article for an outline of the types of pre-insolvency crooks who encourage fraud and ruin businesses.

The types of consultants that market to financially troubled businesses are:

- Public practice accountants

- Contract chief financial officers (financial accountants)

- Small business financial counsellors

- Insolvency practitioners

- Insolvency lawyers

- Operational turnaround consultants

Kate Carnell, the Australian Small Business and Family Enterprise Ombudsman has issued stark warnings about phoenix operators and pre-insolvency advisers, as evidenced in the quote included at the beginning of this article. She has warned that phoenixing “destroys small businesses” – by allowing debtors to escape their liabilities upon which small businesses may be relying for income and cash flow. In addition, the ASIC uses regulatory strategies to disrupt illegal phoenix activity and warns that they may take action where “evidence shows that directors intentionally misused company assets or acted in a way that is contrary to the company’s best interests”. Commenting on the financial year ending in June 2019, Commissioner Price revealed that ASIC prosecuted 382 people for 827 offences of failure to keep books and records, a key indicator of phoenix activity. The estimated cost of phoenix activity to businesses is between $1.1 to $3.1 billion each year. This estimation is so broad because, as noted by Helen Anderson and others in the second report from the Regulating Fraudulent Phoenix Activity Project released in 2015, no data set is available to make a precise estimation on the cost of phoenix activity to the economy, and all of the numbers are only guesses. This makes tackling phoenix activity all the more difficult.

When should you engage a pre-insolvency adviser?

A pre-insolvency adviser should be engaged when a proprietor suspects that their business is or will be insolvent. Insolvency means that the business can’t pay its debts from its available resources regardless of whether there is an uptick in the near future. It is a chronic shortage of working capital.

The alternative to engaging an external consultant is to conduct a self-assessment of the business or just go into voluntary administration or liquidation. This is usually a poor response because the business proprietor won’t have enough technical knowledge of accounting and the relevant law to navigate the best pathway. The result could be that the proprietors develop a myopic view about their financial position and have no understanding of their legal rights. The value of an external adviser is also that there is a greater chance of impartiality – whereas the proprietor will find it difficult to just work ‘on’ the business rather than ‘in’ it. When a business faces a financial crisis, the proprietors can often spend all of their time putting out fires without noticing that the fires are growing in size and they then miss the chance to save anything. Currently, there are no restrictions on the advisory framework. Some were recommended in the Productivity Commission’s 2015 report but as yet they have not been implemented. One recommendation was that a registered “Restructuring Advisor” accreditation be created to ensure that quality advisors can be readily identified.

How do I know if I am insolvent or on the path to becoming insolvent? The symptoms

There are many signs and symptoms that can flag that a business may be approaching insolvency. These can be broadly sorted into two categories: forward indicators and lagging indicators.

Forward indicators are early signs of issues with the structure of the business that may lead it into insolvency. These include poor business models and excessive personal spending. The most reliable forward indicator of insolvency is the maintenance of insufficient working capital and successive years of losses. Additionally, if the business relies on one key person and that key person loses passion for the business and their application subsides, this is also a key forward indicator of insolvency.

Lagging indicators are ‘last call’ red flags which cannot be ignored, and could mean that the business is already insolvent. These include statutory demands from creditors and formal ATO demands for tax debts or Court notices. In these cases, the business is deferring payments of non-essential creditors because it doesn’t have enough working capital to properly fund business operations.

There will always be forward indicators that proprietors should look at carefully if their business is headed towards turbulent times. The forward indicators may not be the ultimate cause of insolvency but they will likely become a critical part of it. If there is a market downturn (a normal event in any economic cycle), this may combine with thin working capital, absence of a key person through depression or anxiety and low profitability to cause business insolvency.

Poor bookkeeping (forward indicator)

Poor organisation and record keeping are often indications of poor financial literacy at best and fraud at worst. Bad bookkeeping makes solvency difficult to prove and is often a sign that businesses are struggling to conduct business operations properly. It will not be possible for financial analysis to be undertaken unless the business’ financial accounts are up-to-date and fully reconciled.

Personal guarantees/director loans/not taking a salary (forward indicator)

Where directors have personally guaranteed business loans over the long term, invested significant amounts of their own money into the business and are no longer taking a salary or receiving repayments it is a bad sign for the business. If working directors can’t draw down a salary and pay dividends, then the sustainability of the business should be questioned. If directors take money out of the business via a director’s loan account this will need to be examined before any winding up of the company because the liquidator may claim the entire amount from the director personally.

Angry creditors (forward indicator)

When creditors come knocking, it is almost always because they have lost faith in the business and are anxious to get their money back before things go sour. Directors need to ask themselves what it is that is making creditors worried, if they can reasonably allay these concerns and if they are actually able to pay them back. This is a forward indicator because it shows that the directors are ignoring routine problems that should be managed pro-actively.

Late debtor payments (forward indicator)

If customers are late with payments, it is likely to cause liquidity issues. Bad customers can spell the end of a business and if key clients or multiple clients are late with payments, businesses will feel the sting. It is a forward indicator because it foreshadows accounting adjustments and write-offs down the track.

High staff turnover/forced holidays (forward indicator)

If staff don’t stay put in the company for long, this will end up being a huge cost to the business in loss of human capital and expenses in constantly training new staff. Directors should also ask themselves what it is about company culture or prospects that is making staff leave. Unusual shutdowns that force staff to take holidays is also a sign that the business model is not working and insolvency may be ahead.

Inability to obtain finance (forward indicator)

If lenders are skittish or unwilling, it is unlikely directors will be able to obtain the capital necessary to fix or change problems the business is facing or may face. SMEs often have a difficult time trying to obtain appropriately priced finance and fall victim to usurious rates of interest from credit card companies, caveat lenders and debt factoring.

Growing broke (forward indicator)

Fast growth without strategy and financial planning behind it may lead to excessive costs and no way to pay them back. Directors should look to their working capital turnover ratio to identify if they are growing at an unsustainable rate. The more sales that a business writes, the more employees, materials and systems they need to cope. The costs of growth are paid for before the income is received and this leads to the observation that businesses can “grow broke”. This means that a business may need to turn away customers that are not in their target market.

Failure of related entity (forward indicator)

The failure of an associated entity on which the original entity relies may lead to an impossible situation where the business cannot function. Similar to the phenomenon of ‘sexually transmitted debt’ in marriages, if a good business is in bed with a bad business, it can be difficult for the viable company to detangle itself from the web of debts and obligations when creditors come knocking.

Problems in the personal lives of directors (forward indicator)

If directors are experiencing personal problems such as chronic or terminal illness, drug or alcohol addiction, family breakdown or something else that is impacting their ability to properly run the business, they will need to delegate their duties to ensure the continuity of the business.

However, problems in the personal lives of directors aren’t always that easy to label or quantify – sometimes business failure can be caused by a loss of energy, motivation or drive as business owners age, obligations mount and passion fades. The energy of the 30s can be lost in the 40s and 50s, and as a root cause issue, it can cause significant problems for company management in the long term.

No interest from purchasers (forward indicator)

Every business needs to have an exit strategy. If the business cannot be sold, then it is completely dependent on the energy of the owner to continue because there is no one willing to take their place.

If directors have already tried to sell the business and there is no interest, it is a bad indicator for the viability of the company long term. Directors need to ask themselves why their business is not an attractive purchase – it is likely that poor accounting and a flawed business model is the root cause underlying this symptom.

Missed BAS lodgement or payment (lagging indicator)

Businesses are required to lodge and pay your Business Activity Statement (BAS) quarterly. Even if you have a tax agent or accountant, it is ultimately the responsibility of directors to meet these obligations. For continued failures to lodge, the ATO is likely to apply penalties.

A missed BAS lodgement or payment may be a result of insufficient cash flow, poor bookkeeping or both. It indicates that a business is not meeting its legal obligations, which is not a sustainable business model.

Due to director penalties now extending to GST as well as PAYG it is strongly recommended that all businesses prioritise filing of BAS returns. Many SMEs are misguided in assuming that they get more time through failing to file BAS returns when the result may be that the directors breach lodgement deadlines and then incur personal liability through a ‘lockdown’ director penalty notice for GST and PAYG tax debt.

Unpaid payroll or super (lagging indicator)

A backlog of unpaid payroll or super for employees is a key sign a business is struggling. It is unlikely employees will stick around for long if they aren’t getting paid and if key employees jump ship, this will likely severely limit business operations and further exacerbate financial issues.

Failing to pay superannuation and entitlements can lead to director’s being personally liable for these debts due to the accessorial liability provisions of the Fair Work Act.

Negative working capital and poor liquidity/repayment plans and write-offs (lagging indicator)

Negative working capital refers to a situation where current liabilities exceed current assets according to the firm’s balance sheet – essentially, there are more debts payable than there are realisable assets and the firm is operating with a foreseeable working capital shortage. Negative working capital may be temporary if a big expense has not yet started reaping returns, but an endemic shortage of working capital is definitive of insolvency and it is not sustainable.

The obvious response to a shortage of working capital is to negotiate payment plans with creditors or for the directors to lend money to the company. This is a deferral strategy and ultimately the debts will need to be paid. Under Australian law, the voluntary administration process will need to be utilised to obtain a waiver of debts.

Issues with the ATO and auditors (lagging indicator)

If directors are constantly receiving correspondence demanding payment from the ATO it is likely that they are being investigated for failures to meet their obligations. This will not be sustainable and the ATO will step in if communication breaks down and the business is consistently unable to comply with instalment arrangements. Most businesses that go into liquidation have tax debts, so this is not exceptional, but the ATO is now more assertive in making claims against directors personally than in the past through director penalty notices and funding liquidators.

Continuing losses: profit and customers (lagging indicators)

It is trite to point out that a business with continual year on year losses will become insolvent. This may also be linked to the numbers of customers that are lost each year because it means that businesses with a high turnover of customers will need significant marketing efforts to maintain a necessary customer base. Every business has ups and down but the combination of accounting losses and a high turnover of customers is an indicator that there is a fundamental problem with the business model that may lead to insolvency once the energy levels and investments of the owners subside.

Significant adverse event (lagging indicator)

Unprecedented disasters such as significant stock damage or loss due to a transport issue, property damage due to weather, or something as unexpected as a huge decline in sales due to COVID-19 can be enough to tip a struggling company over the edge. These events may sometimes be predictable but when combined with other fundamental business problems the business can be tipped into insolvency.

Final stages (very lagging indicators)

These are the key ‘last call’ symptoms that signal imminent danger for your business before liquidation or voluntary administration.

- Litigation or judgment debts

- Eviction notice

- Application to wind up

What is a zombie company (and the root causes)?

A zombie company is a business that barely scrapes by and is always short of cash. In accounting terms, it covers most of its running costs but is never able to develop a maintainable profit margin. Zombie companies are weak businesses prone to failure.

Zombie companies are often found in the following industries: building and construction, transport, retail and hospitality, professional services and mining services.

Zombie companies can’t stay zombies forever. At some point, something will give and they are therefore the kinds of businesses that should seek out the assistance of pre-insolvency advisers.

Zombie companies often exhibit the signs or forward indicators of insolvency, but not necessarily the symptoms or lagging indicators. There are root cause issues at play in the business, but these have not yet created a big enough problem for directors to recognise. However, zombie companies constantly teeter on the edge of insolvency, and if they wait for lagging indicators instead of acting on the early signs, they could be toppled over the edge by just a light breeze. An example would be where a predictable risk event such as a recession or a change in consumer preferences takes effect.

In his book, ‘Corporate Turnaround Artistry’, Jeff Sands outlines the ‘business killers’ (AKA root causes) that characterise zombie companies and predispose them to failure. These root cause issues must be differentiated from symptoms of failure, which indicate that the business is struggling, but are not the reason why. Understanding the difference between root causes and symptoms is vital for a business looking to initiate a turnaround.

Some key business killers/root cause issues according to Jeff Sands include:

- Failure to adapt – How directors understand and respond to economic change can determine longevity.

- Bad luck – Bad luck exists – factory fires, ill health and natural disasters are all examples of how it can affect a business.

- Undercapitalised – A strong balance sheet can help you through the worst storms in business.

- Overlevered – Similar to undercapitalised but more dangerous.

- Not diversified – Risk minimisation is important to attract investors and remain sustainable.

- Lacking controls – For many businesses, lack of controls gets them into trouble because they simply don’t see trouble developing and if they do, they often misread the magnitude.

- Overanalysing – Measuring too much can create confusion and reduce understanding of core business principles.

- Low gross product margin – Sales minus the variable cost of your product or service.

- Rising costs – Rising costs need to be fought aggressively and quickly passed on to customers.

- Owner health or distraction – If the owner is unable or unwilling to run their business, it is likely to affect performance.

- Overexpansion – Nations and businesses both fail by living beyond their means.

- Overcomplicating – Business is simple: buy low, sell high, keep most of the spread. Don’t lose sight of that. If you can’t explain it to your board in one typed page, you probably shouldn’t be doing it.

- Failure to control a crisis – How you react will magnify or reduce the impact.

- Management transition – The change in style and approach can have flow on effects.

- Reading too much pop-management – Taking the new-age hype over office foosball tables and beanbags too far can lead to debt and unsatisfied staff.

- Falling in love with your product – It may be perfect in your eyes, but the consumer’s view is what matters.

- Entrepreneurial stubbornness – Doubling down on the same old thing will kill your credibility.

- Leadership – Where a conflict of interest arises between the staff and the business, the owner must take a strong lead.

What is the turnaround process?

The turnaround process is the steps and stages a company goes through on its way out of a crisis and towards sustainability. According to Jeff Sands in his book, ‘Corporate Turnaround Artistry’ there are several key steps in the turnaround process, which we will summarise here.

- Stabilising – After the initial shock, you need to assess the business for the biggest problems and work on them as an absolute priority. Aggressively pitch for a key customer’s business, negotiate leniency with your lender, appeal a regulatory decision, or do whatever it is you need to do to buy yourself time to meaningfully restructure.

- Overreacting – Cutting costs is uncomfortable and its likely you’ll feel like you’re overdoing it – there is no such thing.

- Creating cash – Pulling cash off your balance sheet and the balance sheets off your customers and vendors. This cash funds the turnaround and protects value.

- Diagnosis – Look at the profit and loss statement to figure out where the structural problems are in the business, and evaluate the gross profit margin. Look at labour, insurances, facilities and interest and identify the biggest drains on cash.

- Reorganising – If you don’t know what revenue is going to be, make a conservative guess and build a plan to be profitable around it. This is not budgeting, but rather forecasting cash flows and finding ways to stay in the green throughout.

- The turnaround plan – You need to sell this plan to lenders, vendors, employees and customers. It must be better than a liquidation and simple to understand: cutting costs and raising prices.

- Executing the turnaround – Move quickly and all at once. Shock the system and then focus on recovery – rip off the bandaid and then build confidence and morale.

- Restructure your debts around the new business – Show creditors how your business can survive, regain health and how much debt it can repay.

- Growing or selling once the turnaround is complete – Congratulations!

What do effective pre-insolvency advisers recommend?

Effective pre-insolvency advisers will look to find the root cause of liquidity issues. They will identify what is causing financial troubles and consider the options for fixing these problems instead of providing a band-aid solution to lagging indicators. This is analogous to the way a doctor looks to treat the broken bones rather than just administering pain medication.

In order to do this effectively, they should concurrently take stock of the company’s assets and liabilities and determine whether or not the company is insolvent. The next step is to advise a course of action, based on the information they have gathered. There are three main options for businesses in a pre-insolvency scenario.

Informal restructure (safe harbour)

At this point, pre-insolvency advisers may advise on changing the customer mix and abandoning bad payers or non-optimal customers, downsizing and letting go of staff, reducing the product offering and writing a new business plan. They may also assist with keeping better financial records and actively managing credit. This may be done through the use of the safe harbour from insolvent trading; for more information, read our article about the safe harbour. Any adviser that recommends a radical change in business strategy should be sacked. A downsizing strategy is likely to be the best for lasting viability.

Formal restructure (voluntary administration)

Voluntary administration is the legal process that occurs when a company is insolvent and an independent, qualified outsider (known as the voluntary administrator) is appointed to review the company’s future. Once appointed, the voluntary administrator takes control from the directors and has full power over the company. Voluntary administrations are largely unsuccessful in Australia; for more information, read our article.

Business closure (liquidation)

A liquidation is the legal process that occurs when a company is formally wound up. An independent, qualified outsider (known as the liquidator) will take control of the company and sell off its assets in order to pay its debts in order of priority. Liquidations often result in the ‘fire sale’ of assets for well below market value, and can be a very costly process that provides minimal returns for creditors.

What are common turnaround mistakes? The Survival Trap

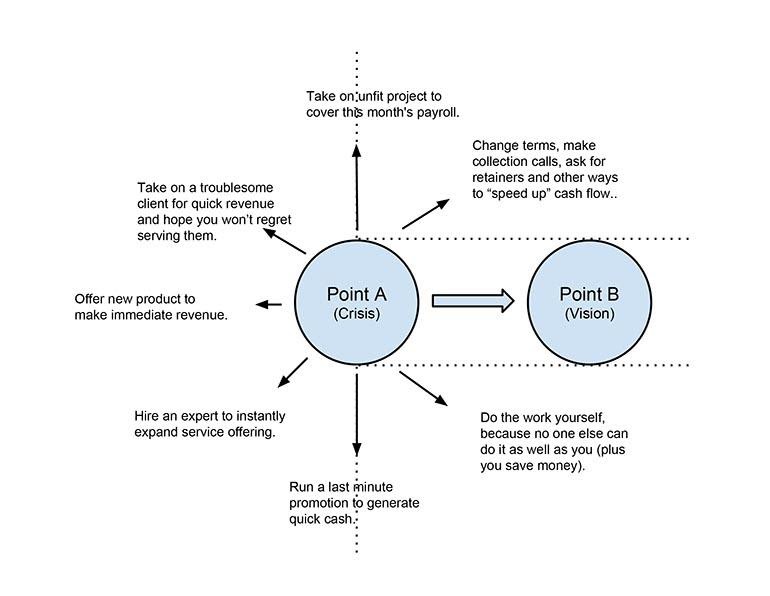

Mike Michalowicz, in his book ‘Profit First’ outlines the common mistakes made by business owners trying to dig themselves out of financial trouble through a model he calls ‘The Survival Trap’ (see Figure 1 below). When a business is struggling to meet payment deadlines, owners and directors often make a series of key errors in trying to get from Point A (crisis) to Point B (vision for the future). However, the panic associated with finding yourself at Point A gives way to desperation and urgency and directors often fail to clearly define what Point B looks like: i.e. what your primary product and service offerings should be and who your ideal clients are. Instead, Point B becomes “enough money to pay the bills and get through the month”. If directors fail to clearly envisage their actual, long-term Point B and instead focus on alleviating whatever the current wallet squeeze is this month, they won’t ever escape the cycle of operating month to month. Michalowicz advises directors to stay in the channel of the horizontal dotted lines that lead to a real Point B to achieve their vision rather than be distracted by cash flow negative decisions.

While pursuing the mistaken strategies outlined in the Survival Trap might buy you time, it won’t fix any of the underlying root cause issues that got you to Point A (crisis) in the first place, and it doesn’t get you any closer to meaningfully achieving the Point B you envisioned when you first started your business. As Michalowicz warns, you cannot become efficient in a crisis. The following are some common mistakes owners and directors fall into when trying to turnaround their business or escape a crisis.

Unfit projects to cover payroll

It is ill advised to take on projects that do not align with your optimal targets just to try and cover payroll. Band aid solutions and quick fixes often create unforeseen issues down the line. Directors need to discern between investments in the future of the business and expenses that won’t reap returns.

Unfit clients to cover payroll

Do not take on sub-optimal clients just to cover payroll. They will end up costing you more in the long term in both time and money.

Focusing on sales and fast money

Focusing on sales and neglecting operations and administration is an easy way to lose track of your business. Without a clear process for all the cogs in the machine, things will start to fall apart.

Doing all the work yourself

Directors are often guilty of working ‘in’ the business too much and working ‘on’ the business too little, especially in certain industries such as building and construction. Focusing on the day to day and ignoring the big picture problems will not fix the business if it has serious structural issues leading to insolvency.

Last minute promotions

It is not recommended to promote anyone in a time of financial instability. Altering the company structure during financial instability is likely to negatively impact morale and result in more work and cost involved in training and restructuring staff operations, which is unlikely to be managed properly when other stressors are at play.

Hiring an expert to instantly expand

Going out of your depth and expanding your offering is not recommended when you’ve hit rocky times. Hiring an expert is costly, and finding the right one requires initial research and comparison. It is a better business plan to stick to what you know and refine it. Expanding when your business is struggling is usually not a good idea.

Offer a new product or service

The costs associated with new product offerings are significant. It may be a long time before you see any return. Additionally, rushing into new offerings without conducting market research may limit your chances of success. It is important for businesses to differentiate between profitable income and debt-generating income. Directors should seek to identify the costs underlying ‘easy money’ and where they actually want their business to go before rushing into new offerings just to pay the bills.

How do I avoid these turnaround mistakes?

It is human nature to revert to habit during stressful times (i.e. all the time when you are running your own business). Humans are highly illogical, and following rigid accounting formulae for business turnover can be confusing for SME owners and directors (although obtaining accounting advice is incredibly necessary for any business). A profit first approach takes the afterthought of profit from the accounting approach and puts it at the forefront of business decisions in order to prioritise cash flow and profit over revenue and baseless growth. It encourages businesses to take control of the numbers and use them to make meaningful change to business practices. Obtaining professional advice, or at least consulting the appropriate literature and scholarship on successful turnarounds, such as those mentioned in this article, is a good first step.

What should I look for in a pre-insolvency adviser?

Real world experience

Insolvency is a complex area, and the way most cases play out in practice can deviate significantly from what the laws and regulations might suggest. Ask a pre-insolvency adviser for testimonials or contact details from past directors to get a better idea of who you’re engaging and what they can do for you.

Professionalism in pre-insolvency is developed through actual, hands-on experience in turnaround scenarios. This is the most important quality you should look for in a pre-insolvency adviser. The best advice will come from those with significant industry experience advising directors and quantifiable success in orchestrating turnarounds. It can be a dangerous and pothole-ridden road to restructuring, and you want an adviser who has driven this route before and knows which side streets to take and which intersections to avoid.

Memberships and accreditations

A pre-insolvency adviser who has an accreditation is more likely to be accountable and professional. Look for accreditations and registrations such a Chartered Accountant (CA), Certified Practicing Accountant (CPA), Australian Restructuring, Insolvency and Turnaround Association (ARITA), Association for Business Restructuring and Turnaround (ABRT), Australian Financial Security Authority (AFSA), Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC), Turnaround Management Association (TMA) and solicitors with valid Practicing Certificates.

History

What is the employment history of your pre-insolvency adviser? Many pre-insolvency consultants move into the area after being struck off as a liquidator or being convicted of commercial crimes. These people should obviously be avoided. It is important to investigate further than the current service offering and take a look at the history of your potential pre-insolvency adviser so you know who you will be dealing with.

Pricing

It is important to understand how a pre-insolvency adviser may charge you, especially when money is tight. Look for fixed fees over hourly rates, as this is more transparent and will allow you to budget more accurately. Many pre-insolvency advisers will validly require up-front deposits to ensure they are paid; be sure to read these agreements carefully. If it is not immediately apparent how the person is pricing their services or it is not transparent then this should be questioned.

Ethics

You need to engage a pre-insolvency adviser who operates legally and ethically. If they are willing to bend the rules in your favour, it is more than likely that they may also be willing to bend the rules to your detriment down the line. Do not risk engaging a pre-insolvency adviser with questionable ethics. If someone is prepared to commit fraud in your name, they will also be prepared to commit fraud against you.

Strategy

Before you engage a pre-insolvency adviser, ask them what their strategy will be. It is important to be aware of how things will move forward and that you are comfortable with what you will be paying for. Shop around and see which practitioner’s strategy aligns best with your goals.

Conflicts of interest

Any reputable adviser, especially lawyers, should conduct a rigorous conflict of interest check to ensure that your matter presents no conflicts with existing or past clients. An adviser should not take on a client where a conflict exists as it could have professional repercussions and interfere with their ability to act unencumbered on your behalf.

Excessive workload

Even the best pre-insolvency adviser won’t be very helpful to you if they don’t have the time and resources to allocate to your business. Make sure that whoever you are engaging has the capacity to take on your matter and isn’t overwhelmed with a range of obligations to a range of clients.

What are common mistaken strategies used to respond to financial problems?

No working capital planning

A failure to plan for sustainable working capital can lead businesses to spiral into insolvency by taking on bad debt.

Illegal phoenix activity

Phoenix activity occurs where there is ‘rebirthing’ of an enterprise by stripping one company of its assets and transferring them into a new entity which is essentially the same business. It is illegal in some forms but is poorly regulated and defined. Nonetheless, businesses engaging in illegal phoenix activity can get into serious trouble. Read our article to find out more about phoenix activity. Note that there are now tighter laws in place to restrict asset stripping through the recovery of ‘creditor-defeating dispositions’.

Suggestions to breach the Corporations Act and directors’ duties

Breaches of the Corporations Act and the directors’ duties can invoke personal liability for directors down the track. It is unwise to resort to illegality just to save a failing business, and it will end up costing you more money and potentially your career.

“Too good to be true” loans

Loans that are too good to be true often are. Any loan agreement should be carefully read and approved by an independent professional adviser but this can be expensive. Some pre-insolvency advisers are now offering to originate finance and this puts their interests in conflict with their clients to obtain finance for the lowest cost.

Who are the effective pre-insolvency advisers?

Insolvency practitioners

Insolvency practitioners are well versed in the insolvency industry and have many years of study and accreditation behind them. They are thus well equipped to provide you with pre-insolvency advice. An initial consultation with an insolvency practitioner can provide you with an opportunity to use them as a sounding board for ideas before an appointment and to get a feel for their potential strategies. Ask them if they believe a voluntary administration would deliver results for your company and listen carefully to their answer. Voluntary administrations typically fail to deliver results to the vast majority of businesses that engage in the process – read our article to find out more.

Insolvency lawyers

Solicitors who specialise in insolvency law are very effective pre-insolvency advisers. They are able to provide a suite of services, including debt recovery and management, restructuring and turnaround consultancy and legal advice and representation. This means they can see your matter through from start to finish, unlike other advisers who would have to pass your matter on to a lawyer if litigation arises. Lawyers who truly specialise in insolvency are rare, so make sure to check your lawyer’s experience before engaging them.

Experienced businesspeople

Experienced individuals in the fields of business and law make excellent turnaround advisers. A useful example is former Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull. His vast experience in commercial and business law, from start-ups to winding-ups, as well as his reputation in these circles as ethical and hardworking can be seen as the model for a pre-insolvency adviser. Understanding of how business and law interact, and how companies are made and broken is critical, and this can only be gained from extensive experience. Whether a consultant can help you depends on their skills and experience, so you should look for indicators of a wealth of professional knowledge before engaging them. They would be likely to charge contingency fees (% of turnover is the most popular methodology) for these services.

Small business financial counsellors

Small business financial counsellors aim to identify a course of action which will equip the director/s and the business to better manage their circumstances. They can confidentially assess and prepare reports on financial position, cash flow and viability, help prepare for meetings with financiers, identify the need for advice from and prepare for meetings with professional service providers, and provide referrals. Importantly, they do not provide advice but will instead provide businesses with the tools and knowledge necessary to make informed financial and business decisions. Small business financial counsellors are becoming more common thanks to COVID-19 funding, and often specialise in businesses operating outside of city centres in rural towns. A small business financial counsellor may be an important first port of call for SMEs, but they will not be able to fix all of a company’s problems, as they cannot advise on an informal safe harbour restructure or formal restructure through voluntary administration or the new small business restructuring procedure.

Who are the terrible insolvency advisers?

Public accountants

Public accountants are usually terrible insolvency advisers for two key reasons. Firstly, public accountants are answerable to a large number of different clients. This means they will most likely be unable or unwilling to devote the necessary time to manage an insolvent client who they will perceive as a potential bad payer and poor long-term investment. Secondly, accountants are not specifically trained in or experienced with insolvency and all of the legal and regulatory hurdles that come along with it. In the rare case that they do have the time and willingness to help you with your insolvency challenge, they are likely to be out of their depth and this will result in less than optimal management of your situation.

Note: This is not intended to be a general criticism of public accountants. They are a critical professional that SMEs need for a variety of professional services. The critique is that they have neither the time, economic interest or the expertise to apply to turnarounds unless they specialise. Public practice accountants are already professionally stretched because they need to keep up-to-date with tax, finance, trust rules, accounting software, payroll issues and also finance. Expecting a public practice accountant to get a fast handle on a turnaround is unrealistic.

Failed liquidators

Failed liquidators are unlikely to make good pre-insolvency advisers. If these individuals have failed as liquidators, it likely indicates poor commercial acumen and an inability to recognise value and achieve best outcomes for businesses. Simply rebranding oneself as a pre-insolvency adviser and providing guidance at a different stage in the insolvency process is a poor indicator of proficiency. Additionally, these individuals are likely to be focused on winding-up given their history in the area, and may fail to provide a comprehensive overview of the business’ prospects before jumping to liquidation.

Commercial lawyers

Just because a lawyer has commercial training and experience does not mean they are qualified to handle an insolvency challenge. The insolvency industry is unique, and commercial experience does not necessarily translate. Commercial lawyers, although intelligent, ethical and well resourced, simply do not have the specialisation required to navigate business insolvency. If they were meant to be successful business people, they would have already followed that path. Many professionals overestimate their skills – this is called the Dunning-Kruger Effect, a cognitive bias where people cannot recognise their lack of competence due to poor self-awareness, leaving them unable to objectively evaluate their skills. Do not take a professional’s word for it that they are competent in a specific area if they do not have the relevant experience and testimonials to support that claim. In commercial lawyers, the Dunning-Kruger effect results in lawyers trying to take carriage of a restructure without the time or skills to complete the task.

Receivables financiers and short-term lenders

Also known as snake oil salesmen, these kinds of lenders are typically unethical and uninformed. They give out loans to the most desperate, and capitalise on their inability to pay down the line. They are unlikely to have any turnaround experience and will only be able to provide a band-aid solution to cash flow problems, which will later turn into a bigger issue when it comes to paying them back. Their true strategy is often to take advantage of a liquidation scenario to charge higher fees and interest.

Unqualified advisers

Qualifications, be they formal or informal are essential for pre-insolvency advisers. Those who do not have the appropriate affiliations or credentials are unlikely to have the contacts and the authority to act on your behalf, and those who do not have experience in insolvency scenarios will not be able to provide meaningful advice. There are examples of finance brokers who have changed professions to provide pre-insolvency advice but they won’t have any of the requisite knowledge of law or accountancy that would enable them to actually help their clients.

You

It may be tempting for directors to try and restructure their company alone, without a professional adviser, in order to cut costs. This is unlikely to succeed and may open directors up to personal liability and further debt. Obtaining professional advice is one of the best investments you can make in your business. To properly evaluate a business, you need a ‘helicopter view’ and it is almost impossible for directors to get this kind of perspective when they are so closely invested in the business.

Technicians generally

Specialised technicians (i.e. experts in an area that isn’t business turnarounds) are unlikely to possess the breadth of industry knowledge necessary to orchestrate a turnaround or organise a successful formal appointment. Insolvency is a very specific area, and while it may be tempting to engage a technician who is known and trusted by you, it is unlikely they will have the skills and knowledge necessary to help you in a pre-insolvency scenario. For example, this could arise in a scenario where an engineer within the company decides to model a turnaround and makes faulty assumptions regarding cash flow, employee behaviour, customer behaviour and insolvency law.

Pre-insolvency crooks in the news

Stephen O’Neill and John Narramore – SMEs R Us/Solvecorp

An ASIC investigation revealed that pre-insolvency advisers O’Neill and Narramore had advised a director to illegally strip his company of its assets to try and defeat creditors. The money was transferred into the accounts of O’Neill and Narramore and then back to the director and his associates. Both men were charged. Shortly before the ABC reported on O’Neill’s activities, SMEs R Us was rebadged as Solvecorp.

Stuart Ariff (Liquidator)

While liquidator of HR Cook Investments between 2006-9, Stuart Ariff was involved in the transfer of funds totalling $1.18 million with intent to defraud the company, which was solvent when it entered liquidation. In 2011, he was found guilty of 19 criminal charges – 13 under the Crimes Act and 6 under the Corporations Act. Stuart Ariff’s conduct should serve as a stark warning to directors about the motivations of liquidators, especially in pre-insolvency scenarios. Stuart Ariff had a clean record, which he was able to rely upon to enable his fraudulent behaviour. Even liquidators who are not crooks are difficult to trust – they usually charge an hourly rate and are inherently incentivised to draw out the process. Liquidators in pre-insolvency scenarios may also tend to rush you into a liquidation in order to secure their own appointment.

Plutus Payroll

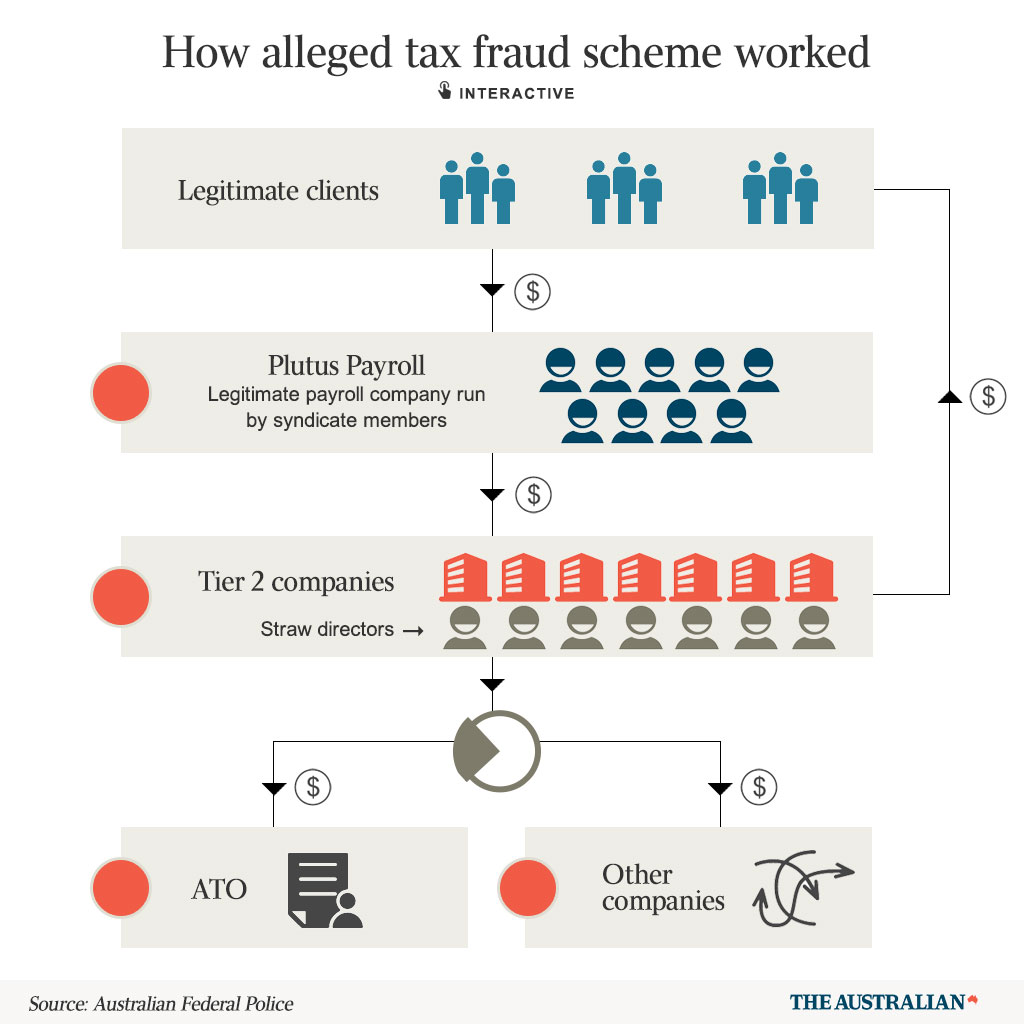

The Plutus Payroll case was a payroll tax scam to divert PAYG withholding owed to the ATO. This was then paid to the clients as a fraud on revenue.

In this case, the operators of the scam took control of Plutus Payroll and its legitimate client base. The clients, outsourcing their payroll, would transfer funds to Plutus to pay the wages and salaries of their employees, with an amount expected to be withheld for PAYG. While wages and salaries, as well as a portion of the PAYG withholdings were paid, the remainder of the PAYG withholdings (often 40% or more of the amount owing by any company) remained with Plutus or was diverted to second tier companies run by dummy directors to protect the identity of the phoenix operators.

These dishonestly obtained funds were then transferred to the scammers through false invoices or other companies’ bank accounts. The account balance and asset pools of the second-tier companies were periodically drained, so that when the ATO initially came looking for the outstanding PAYG liabilities, it would wind up the companies to pay off the debt, and the scammers would lose a relatively small amount. Therefore, to protect and perpetuate the scheme, companies were rebirthed over and over (phoenix activity) to evade the ATO.

The Plutus Payroll scam raised approximately $165 million dollars between June 2016 and May 2017.

The scam moved from being a liquidation issue (that is, something a liquidator would deal with in terms of claw back) to a fraud and crime issue. The Australian Federal Police conducted a thorough investigation into the scam, and have since arrested the operators and some participants.

What should a professional adviser do in a pre-insolvency scenario?

Ensure data entry of all transactions and balance the books first

A professional adviser should ensure that the client’s bookkeepers have entered all financial transactions and reconciled the accounts. It will not be possible to look at insolvency options if the client does not have a clear view about the depth of their financial problems. Reconciled accounts are key to understanding a business’ history and why things have gone wrong. If necessary, a business may need to engage a forensic accountant to properly piece together their account history.

Respond to or manage any ATO, ASIC or Court correspondence

While this is a lagging indicator of insolvency, in order to allow time to deal with root cause issues, an insolvency professional should first establish communication with the relevant bodies to negotiate repayment plans or pause recovery actions. This is part of initiating a debt deferral strategy by obtaining indulgences from creditors for due and payable debts.

Root cause analysis

The most critical element of pre-insolvency advice is identifying not what is going wrong, but why it is going wrong. A professional adviser will look at the business as a whole to identify why it is not able to pay its debts. If the adviser does not undertake this task, it should instead be undertaken by an accountant or a forensic accountant if the task is difficult. Differentiating between symptoms and causes is a key step in getting a clearer picture of the business and its ongoing viability.

Recommend a course of action

Based on the information learned and time and leniency bought in the steps above, a professional adviser should be able to make an informed recommendation on the best course of action for a business. Read above for the three possible outcomes for an insolvent business. If the business is hopelessly insolvent it should be liquidated or at least stop trading. Another option may be to engage the safe harbour from insolvent trading to pursue a restructure. For this, directors must develop a ‘course of action’ that is better than a liquidation and all debts incurred must be linked to it. In the words of Professor Jason Harris of the University of Sydney “hope is not a strategy… an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure”. When developing the course of action, keep the following in mind:

- Before engaging a safe harbour advisor, ensure that tax lodgements and employee entitlements are up to date;

- Keep a record of the terms of engagement with the safe harbour advisor;

- Keep a record of what particular actions have been taken to attempt to provide a better outcome for the company to come within the protection of the safe harbour.

For more information, read our article on the safe harbour.

Look for voidable transactions and act as advocate

A professional adviser should identify any transactions that may be voidable so as to understand the risk to directors of winding up. An insolvency lawyer should then act as the advocate for the directors, both in and out of court, to respond to any personal claims against the directors. Voidable transactions are transfers or payments that are capable of being deemed legally ‘void’ for being illegal or unlawful. For example, in an insolvency scenario, where a transaction violates the pari passu principle (that the remaining assets of a company in insolvency be equally distributed between unsecured creditors), they may be able to be ‘clawed back’ by a liquidator.

Talk to a liquidator

If liquidation is going to be the best course of action for the whole or part of your business, a professional adviser can help put you in contact with a liquidator and communicate your interests to them to assist you down this road. However, it is important to note that unlike conversations with a lawyer, conversations with a liquidator are not subject to legal professional privilege (i.e. confidential) and can and will likely be used in subsequent investigations.

What financial tools should be used to assess the viability of a business?

Du Pont Analysis (ROI)

ROI = Profit / Assets = (Profit / Sales) x (Sales / Assets)

Du Pont Analysis quantifies the components that comprise the key ratio/performance indicator: Return on Investment (i.e. profit/assets expressed as a percentage). It allows businesses to identify what structural changes should be made to improve profitability. It can also identify where the issues are in the business, which allows directors to then turn their focus to addressing these problems.

A pre-insolvency adviser will use Du Pont Analysis to firstly identify your ROI and then break it down into its component parts to determine sales margin and turnover ratio. To improve the sales margin, directors can either raise prices or lower costs, and to improve the turnover ratio, directors can either sell more product or use less assets. Your pre-insolvency adviser may give you suggestions such as changing the product mix, more effective marketing, product rationalisation, sale and lease back of assets, lowering overheads, seeking cheaper financing or improving staff productivity, based on their Du Pont Analysis of your ROI. Long term, you can use Du Pont Analysis to evaluate how effective a restructure has been.

Sustainable growth rate

Sustainable Growth = ROA x (1-D) / (E/A - (ROA) x (1-D))

Sustainable growth rate is a calculation that determines whether a business is growing within its means or “growing broke”. Growing too fast can result in cash flow issues which can run even a profitable business into the ground. If a company is growing, either more equity must be put in or gearing will increase. The formula for sustainable growth is determined by factoring in return on assets, amount of profits retained and the gearing ratio.

Breakeven point

Breakeven point = Fixed costs / Contribution margin per unit

To determine the breakeven point, a pre-insolvency adviser may use contribution analysis. This involves calculating how many sales need to be made to break even (i.e. stop making a loss). It is a very simple tool but a very useful one for businesses that have lost sight of the fundamentals.

What skills will a good insolvency lawyer have? What are the benefits of engaging one?

They can actually work with people and a have a good track record

Ask for references from other directors that they have helped through an insolvency issue so that you can speak to their former clients. If they can’t point you to a happy former client, there is a problem. Ideally, they will be able to point to multiple recent clients, so you can be sure that they are currently and consistently performing their job well. It also helps just to talk to someone who has been through the insolvency process as a director/owner of a company to help demystify what you may face in an insolvency scenario, and how you can expect the matter to generally unfold.

They are thought leaders who know the technical issues

They’ll need to have degrees and have written articles and other materials to be a true professional. Demonstrated knowledge of the technical aspects of the Corporations Act and litigation strategy is essential. However, you don’t want to engage the awkward lawyer who receives referrals from other commercial lawyers in their firm but ultimately doesn’t have their own relationships sufficient to sustain a practice. That type of person may become frustrating to deal with because although they might be book smart, they won’t show courage or leadership when it comes to advocating for you. They may be fine to run a debt recovery claim or write you a memorandum regarding the Corporations Act but they’ll be unable to give you meaningful strategic or tactical guidance that will make a difference.

You can stomach working with their associates

Ask them who they work with or give referrals to because they are likely to be close to certain insolvency practitioners, accountants, finance brokers and other consultants. In the situation that an informal workout isn’t a success, they’ll probably refer you to one of the insolvency practitioners that they are friendly with. They should be able to point you to different insolvency firms (small, medium and large) that may make an appointment as voluntary administrator or liquidator if a turnaround is not feasible, and if this is to occur, you want to ensure that you are comfortable with the people you will potentially be working with.

You have some chemistry

You’ll need to work together very closely, so personal chemistry is important. You could be placed in high-pressure situations and you’ll need to trust their advice without having the time to get a second opinion. Lawyers that specialise in commercial litigation are notoriously difficult characters because it comes with the territory of rough and tumble litigation. It’s better to test them at your first meeting with up-front, direct questions about their professional character rather than taking a passive stance, in order to make sure that you are engaging someone who you can have a productive lawyer-client relationship with.

What are the downsides of insolvency lawyers?

- Charging: Hourly rates apply and they often require funds upfront, can’t charge contingency fees (% of outcome)

- Entrepreneurialism: Insolvency lawyers are unlikely to have entrepreneurial flair – if they did, they would probably be doing something else rather than being insolvency lawyers

- Working with others: They generally run their own show in silos and so they may not be the best at working with others

- A little intransigent: It’s a tough business being an insolvency lawyer so insolvency law tends to attract the more intransigent lawyers because it helps to stick to your guns

What if only part of the business is viable?

If an analysis of a business identifies that only part of its operations are viable but that it is insolvent overall, there may be a chance to save this part. It is a difficult circumstance to navigate in an overall turnaround and will likely involve the termination of employees and contractors as well as the sale of plant and equipment. This may occur formally through voluntary administration or liquidation of the unsustainable part of the business, or informally through the use of the safe harbour from insolvent trading. Technical issues related to the business industry can complicate this process further. The bad news is that the current insolvency regime is not designed to help SMEs save viable parts of their business and the ‘baby is thrown out with the bathwater’ in most voluntary administrations.

Where there exists a viable part of an insolvent business, you will require tailored pre-insolvency advice. A pre-insolvency adviser will be able to help you identify and isolate the performing part of the business and assist you with the process of detaching it from the non-performing part. Then, they will be able to assist you with facilitating the conclusion of the unsustainable part of the business, and provide you with support to manage the newly singular, sustainable business.

What do I do next?

Professional advice is always a smart investment in an insolvency scenario. Sewell & Kettle Lawyers are ready to help you with your insolvency concerns. With significant experience and a specialised focus on debt recovery and insolvency, we are uniquely placed to help you face your commercial challenges. Read more about our legal and insolvency services, and then contact us.