Navigating a Choppy Voluntary Administration: Arresting a boat for a client

Table of contents:

- Summary

- Our clients traded in their boat for another (that was being built in China)

- The seller went into voluntary administration

- No DOCA was proposed, and the company was put into liquidation

- Sewell & Kettle engaged to recover boat and applied for the arrest of the boat

- How did the administrator and the Defendant react to the claim?

- How is a boat arrested?

- The arrest is contested

- What was the outcome?

- Takeaways

- Testimonial from our client for our work

Summary

The Merlion is a mythical creature with the head of a lion and the body of a fish. Our client had the misfortune of trading in their Merlion boat to an insolvent boat builder (Pacific Motor Yachts Pty Ltd) that subsequently went into liquidation. After trying to negotiate the return of the boat, the client engaged Sewell & Kettle to start proceedings in the Admiralty division of the Federal Court to arrest the vessel whilst the issue of ownership was decided by the Federal Court. The action successfully rescued the Merlion and secured it whilst the case progressed. After a successful hearing, the Merlion was returned to our client.

Our clients traded in their boat for another (that was being built in China)

Pacific Motor Yachts Pty Ltd (PMY) was part of a group of companies that sold Clipper Motor Yachts in Australia. It was based at the Gold Coast Marina and sold custom-made motor yachts.

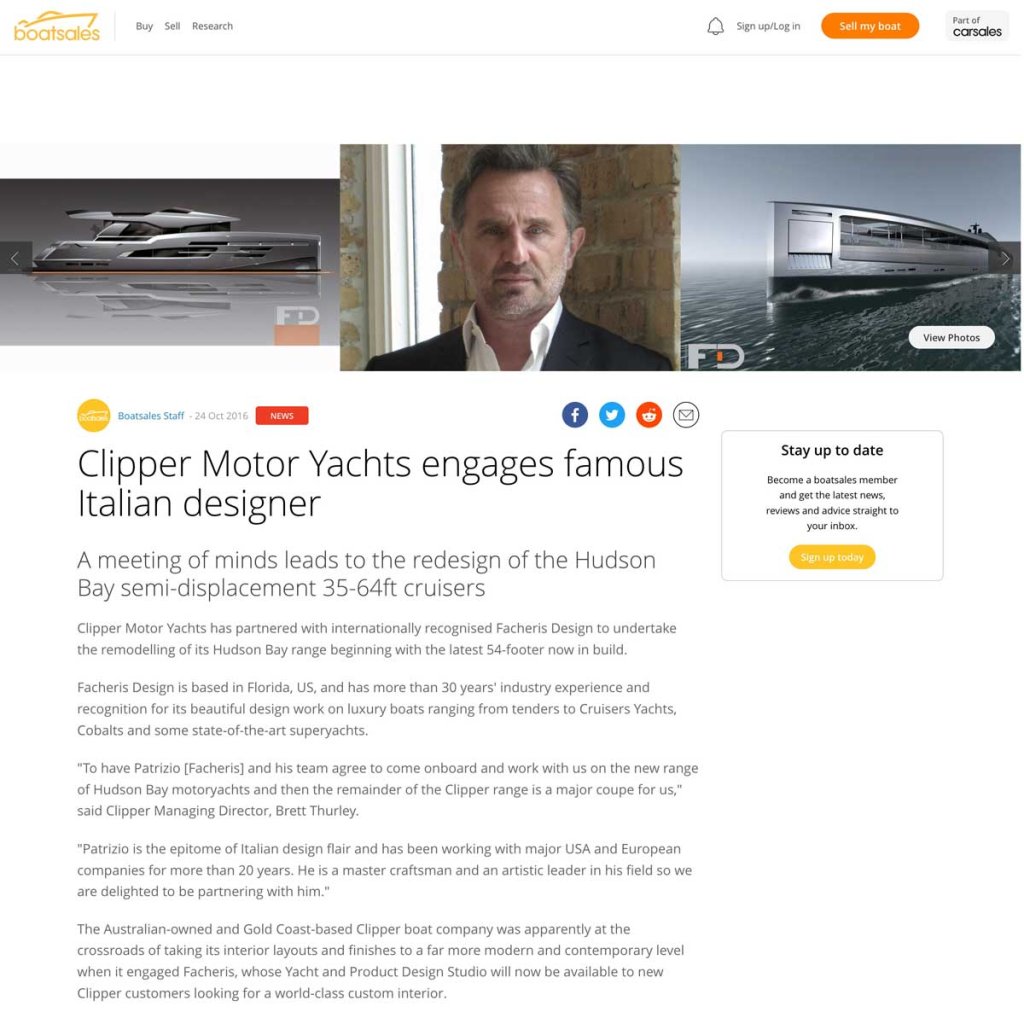

A substantial investment had gone into the design and manufacture of the boats. This included engaging an Italian designer, Farcheris Design.

The voluntary administrators appointed over PMY summed up the company’s business as follows:

Administrator’s Report to Creditors, 23 September 2023, Livingstone, G & Walker, A. p38

PMY traded from leased premises located at Gold Coast City Marina 76 – 84 Waterway Drive Coomera in Queensland. PMY engaged with customers to take orders for boats under the “Clipper” brand and engaged with the Construction Yards located in China, to manufacture the ordered boats. PMY also sold new and used boats throughout its own purchased stock as well as private brokerage.

Critically, for our clients, the boats were not manufactured in Australia. The boats were manufactured in the construction yards in Ningbo, China by manufacturers unrelated to PMY and its director. This effectively meant that those boats were out of the reach of the Australian voluntary administrators and Australian courts.

PMY sold the Merlion to our client in 2022 – a 2023 Clipper Hudson Bay 540. The handover of the Merlion was in December 2022 and from that date our client got clear title and possession of the boat. Clear title is an important foundation of a legal claim.

The Merlion was a splendid boat; it was a 60 foot motor yacht with a powerful engine and an open plan layout for entertaining:

Our client bought one boat from PMY (the Merlion) and after he got that boat he received an offer from PMY’s director to trade-in the Merlion for a more advanced version of the same boat that was under construction. Our client was told another customer had pulled out of a deal to buy the new boat and that its manufacture in China was well-progressed.

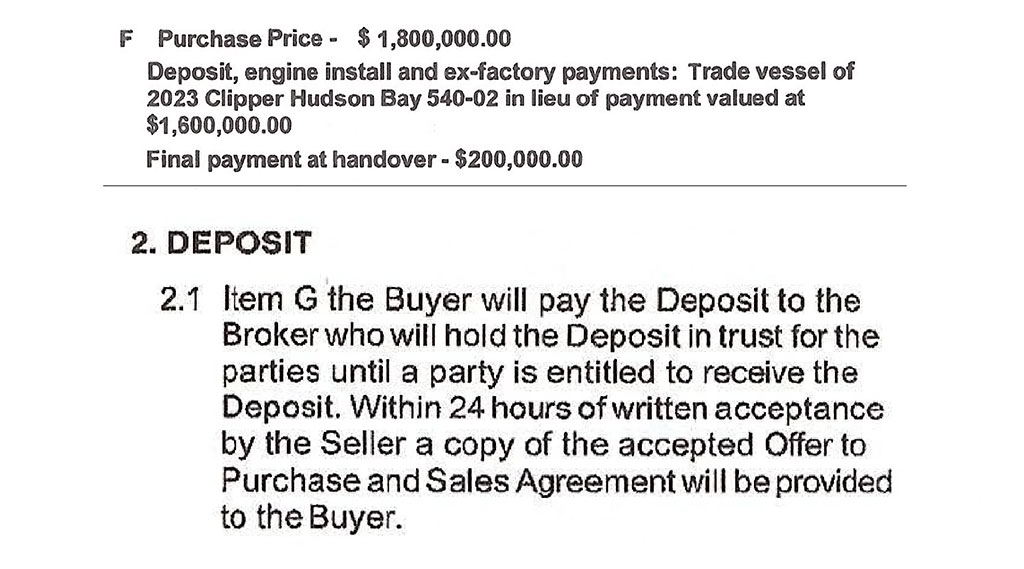

By March 2023, the negotiations for the trade-in of the Merlion were well advanced. The deal that was struck with PMY was that our client would trade-in the Merlion and receive a new boat and pay additional cash in exchange for the new boat. These negotiations were concluded at the end of May 2023 and then a contract was signed in June of 2023.

Critically, the contractual document for the trade-in was very poorly drafted yet signed by both PMY and our client. The contract was described as “higgledy-piggledly” by Justice Derrington of the Federal Court after she read it.

The contract was prepared by PMY, and key excerpts of it (pertinent to the legal issues that arose) are:

The legal status of the boat when possession was handed over became the definitive legal issue in the case. The express terms of the contract (i.e. the written words) assisted our client because it supported an argument that the boat was a ‘deposit’ (as defined by the contract terms) and was meant to be held on trust by PMY. This contrasts with what would generally be expected of a trade-in transaction because it would be expected that both title and possession would transfer so that the trade-in vessel could quickly be resold by the retailer.

Justice S C Derrington summed up the deal in her judgment as:

Burrows v The Ship ‘Merlion’ [2024] FCA 220 at paragraph 12

In June of 2023 the Merlion was handed over by our client to the director of PMY as the trade-in for the new boat. Subsequently, without our client’s knowledge, the director of PMY transferred the Merlion to a third party (the Defendant in our future proceedings) to settle debts allegedly owed to the Defendant by PMY. This claim was contested by our client at the hearing of the case.

Sometime in August of 2023 the Defendant then advertised the Merlion for sale on a boat sale website. Thankfully for our client it didn’t sell and it remained in the possession of the Defendant until proceedings could be commenced.

PMY had one director who set up the deals with our client but our client’s dispute ended up being with the third party the director transferred the Merlion to. It is also interesting that the voluntary administrators didn’t jump into the fray to make a claim for the Merlion.

The seller went into voluntary administration

On 29 August 2023 PMY and three related companies (Cobalt of Australia Pty Ltd, Bennington Boats of Australia and Thurley Marine Pty Ltd) went into voluntary administration. In Australia insolvent companies (with >$1m in debt) can either go into voluntary administration or liquidation. Most companies with assets and active trading go into voluntary administration because it opens the possibility of the rescue of the business through a compromise with its creditors. This contrasts with a liquidation where the business ceases to trade immediately.

However, one characteristic of voluntary administration is that the voluntary administrators won’t continue trading if a business is not cash flow positive. The voluntary administration regime in Australia encourages the voluntary administrators to be conservative because if there is a shortfall on trading receipts whilst a company is in voluntary administration they will be personally liable for it. As accountants who rely on hourly billing there is zero chance voluntary administrators will agree to risk their personal assets by continuing to trade a company that is not cash flow positive during the period of the administration (about 6 weeks).

At the time that PMY went into voluntary administration it had 11 ongoing boatbuilding projects running in China. This meant that 11 boats were under construction, each at a different stage of development. For our purposes this is very significant because those boats were not under the control (or even ownership) of PMY and therefore the boatbuilding WIP (as an asset) that was recorded on PMY’s balance sheet was out of the reach of the voluntary administrators. The voluntary administrators did not even hazard going to China to inspect the boats.

Standard PMY contracts required customers to make progress payments towards construction of their boats based upon the stage of completion. That would mean that by the time of delivery the customer would have completely paid for the boat and that they would bear risk that if PMY failed the Chinese manufacturer would keep the boats under construction to satisfy them for any obligations it was owed by PMY.

Unfortunately, at the time that PMY went into voluntary administration, it was not square with its Chinese boat manufacturer. PMY was in significant arrears with the Chinese boatyards and all work on the customer’s boats stopped. The administrators of PMY found that they didn’t have enough cash-at-bank to finance the continuation of boat building in China so they weren’t able to enter into any settlement with the manufacturers. The boat makers were canny enough to sit on their partially constructed boats whilst the voluntary administration process ran out.

In a forensic finding that was very concerning for our client the administrators’ report determined that PMY had been insolvent since June of 2022 and this meant that the company was insolvent when it negotiated the trade-in deal with our client. This gave rise to a concern that the trade-in was undertaken by PMY with a motive of quickly raising cash by obtaining a readily marketable boat (the Merlion) in exchange for a boat that wouldn’t be constructed.

The voluntary administrator’s accounting analysis found that the company had a $23 million asset deficiency. This is an astounding figure given the scale of the operation of PMY:

FINANCIAL POSITION – PMY

| Pacific Motor Yachts | ROCAP | Administrators’ ERV |

|---|---|---|

| Assets | ||

| Cash At Bank | – | 19,250 |

| Debtors | 6,257,332 | 10,000 |

| WIP | 9,000,000 | – |

| Plant and equipment | 213,661 | 79,500 |

| Other Assets | 16,667 | – |

| Total Assets | 15,487,660 | 108,750 |

| Liabilities | ||

| Secured Creditors | – | |

| Unsecured | 21,771,379 | 23,785,280 |

| Total Liabilities | 21,771,379 | 23,785,280 |

| Estimated (Deficiency) / Surplus | (6,283,719) | (23,676,530) |

One very alarming fact that was reported on by the voluntary administrators was that PMY didn’t have a bank account, and it transacted through the bank account of a related entity. The administrators didn’t cast any aspersions about the motives for this action in their report. But this meant that there was literally no cash-at-bank when the voluntary administrators were appointed. The result for the 11 customers of PMY with boats under construction was that their progress payments for boat construction weren’t separately accounted for so the client monies were co-mingled.

The complete lack of cash, the breakdown in the relationship with the Chinese boat builders and the administrator’s weak position dealing with China generally resulted in the administrators determining that they needed to disclaim the boat building contracts. This meant that they terminated the contracts and left the customers to make claims as unsecured creditors.

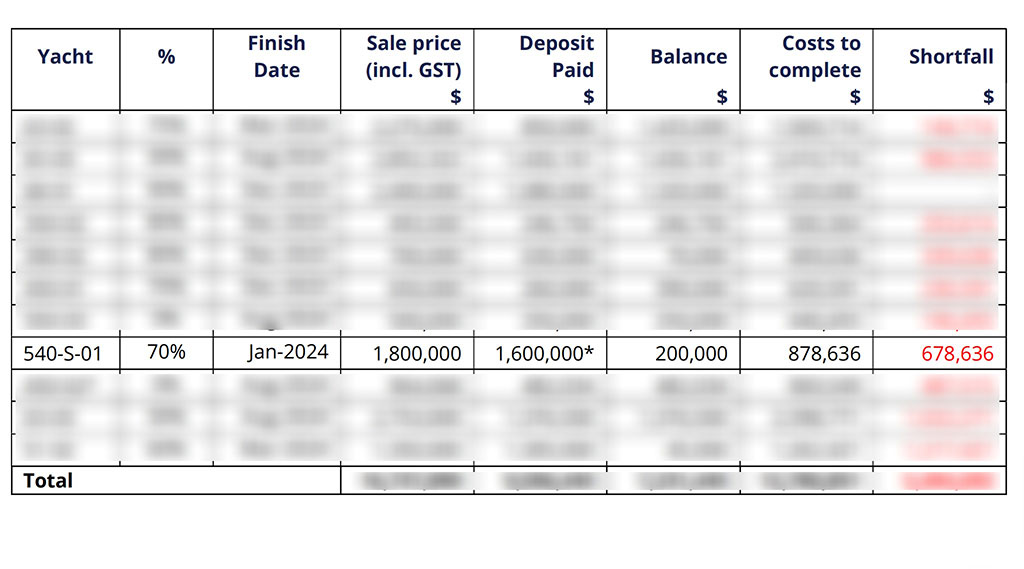

The administrators found that our client’s new boat in China was 70% completed but this was one of the boat construction contracts that were disclaimed by the administrators. In particular, the administrator’s analysis was that a cash payment of $678,636 was required to complete the boat:

Given the administrator’s decision to disclaim the boat building contracts our client elected to terminate the sale agreement and claim damages and the return of the Merlion. What our client didn’t know at the start of the voluntary administration was that the Merlion was not in the possession of PMY. Further, at some time before the administration commenced the Merlion had been moved from PMY’s mooring on the Gold Coast to the Defendant’s private residence.

Sensibly, our client contacted the Defendant and asked for him to return the boat to them but he refused. The Defendant informed our client that he received the Merlion from PMY to settle debts that PMY owed to him:

He believes he has received the boat in good faith and has ownership. He claims that the transfer occurred sometime in July 2023. He outlined his connection to Brett Thurley as a friend and unsecured creditor to the value of approximately $3.5m for the purchase of boats, engines, freight etc over many years with no business connection. He does not take profit but charges 7% interest on the loans.

Although it did not become a live issue to be decided by a Court our view was that the Defendant was a silent partner of the director of PMY, not just a passive investor. Any transaction between the PMY and the defendant, therefore, was not an arm’s length transaction (i.e. a bone fide translation for value without notice).

No DOCA was proposed, and the company was put into liquidation

The voluntary administrators and the director of PMY worked to develop a proposal to enter into a compromise with creditors. In the voluntary administration regime if that proposal is accepted by creditors it is documented through a deed of company arrangement (a DOCA). However, no DOCA was proposed and because of this the administrators had no choice but to recommend to creditors that PMY should be put into liquidation. The administrators found that PMY was terminal because it had a lot of debt and almost no assets.

In the voluntary administration regime, there are two mandatory meetings of creditors. At the second meeting of creditors there is a vote, and the creditors decide on the future of the company. If the creditors vote against a DOCA or no DOCA is proposed the company will immediately go into liquidation.

PMY went into liquidation on 3 October 2023 and at that time the Merlion was still being held by the Defendant at their private wharf on the Gold Coast.

The administrator’s report concluded that there was also no chance of a going-concern sale of PMY. They found that the business had negligible goodwill and that any sale of business would not include any WIP (i.e the partially constructed boats).

The administrators’ investigations found that 8 yachts under construction were based upon fixed-price contracts and it was nevertheless uncommercial to complete those projects. The fixed-price didn’t cover the costs required by the manufacturer to complete those projects.

The administrators report didn’t discuss the business relationship of the director of PMY and the Defendant. The administrator’s report was broadly supportive of the Defendant’s claim that it was transferred in partial satisfaction of an unsecured loan. That was disappointing for our client, and it meant they had to conduct their own investigations.

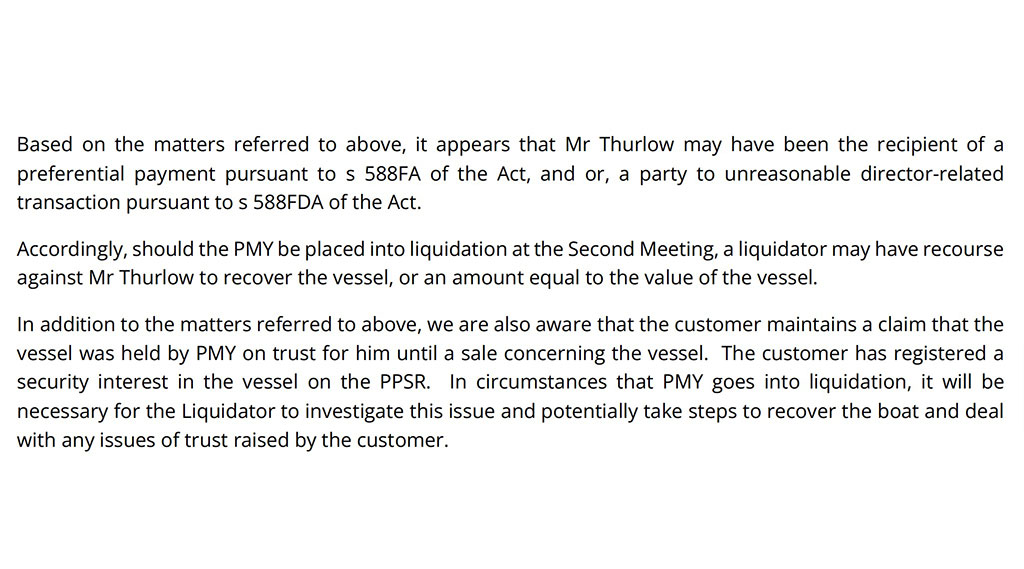

The administrator’s report set out their own claim for the Merlion as a voidable transaction. This meant that there may be a three-way contest for the Merlion. The analysis from their report is set out below:

Sewell & Kettle engaged to recover boat and applied for the arrest of the boat

When Sewell & Kettle were engaged our client faced the risk of a complete loss:

- They had agreed to trade-in the Merlion without any registered security interest (such as a PMSI) over the boat

- Their new boat in China was incomplete and its construction contract had been disclaimed by the voluntary administrators of PMY

- There was no contractual basis to claim the partly built boat in China or maintain any claim over it

- Their trade-in boat (the Merlion) had been transferred by PMY to a third party (the Defendant)

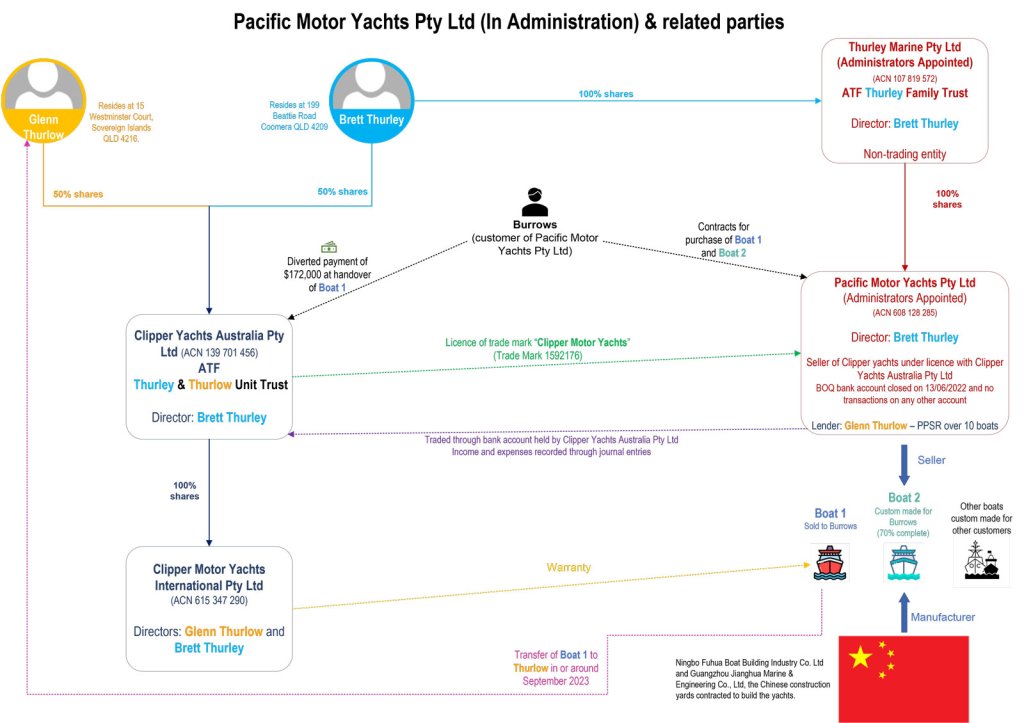

Our immediate concern was that the Merlion was not in the administrators’ possession, posing a real risk of disposal. Our investigations found that there was a close business relationship between PMY’s sole director and the Defendant that went beyond that of a debtor/creditor relationship. The flowchart we created below was admitted into evidence into the Federal Court hearing (and the information was not objected to as being inaccurate):

At the end of September 2023, we issued a letter of demand to the Defendant. The letter demanded the immediate return of the Merlion and if it was not complied with then we foreshadowed litigation would be commenced to recover the boat.

The letter of demand was rejected by the Defendant and our client made the decision that they could only recover the Merlion through litigation. We initially considered an injunction but when this was compared to the arrest procedure in the Admiralty division of the Federal court it was going to be more expensive and slower. From a technical point of view our client’s sole objective was to recover the Merlion from the Defendant and not to commence any damages claim another party.

The scope of action that our client required (boat recovery) meant that the arrest procedure in the Admiralty division of the Federal Court was a cost-effective litigation option. The claim that we commenced was in rem and this meant that from a legal point of view the action was against the boat itself (rather than a corporate or individual defendant).

What does the arrest of the vessel mean? The arrest of a vessel in the Admiralty Division of the Federal Court is a legal process used to secure claims against a ship or its owner through Admiralty jurisdiction. It involves the detention of the ship by court order, preventing it from leaving port until the claim is resolved or adequate security is provided. Arresting a vessel is a powerful remedy that ensures the claimant has access to the ship as security for their claim and it compels the owner to address the legal proceedings.

In October of 2023 our client commenced a claim in rem against the Merlion in the Admiralty division of the Federal Court. The claim sought a declaration that our client was the sole beneficial owner of the Merlion. To support the claim for possession of the Merlion it was necessary to set out the legal basis of the claim (i.e. the cause of action). We advanced multiple claims including breach of trust, sham, detinue, conversion and conveyance of property intended to defraud.

One of the key legal claims was for conversion, a somewhat obscure cause of action. What is a claim for conversion? It is a claim for wrongful interference with goods with a remedy of the return of the goods to the owner. Our claim was that the Merlion was held on trust by PMY and that the Defendant’s refusal to return the Merlion to our client was an act of wrongful interference with goods by the Defendant. The relationship between the director of PMY and the Defendant (as silent partners) meant that the transfer of the Merlion by PMY to the Defendant was not a bone fide transfer for value without notice.

The documents that are required to be prepared to support the arrest include the following:

- Writ

- Statement of claim

- Affidavits

- Draft enforcement documents

- Communications with court officers

How did the administrator and the Defendant react to the claim?

There were (at least) three key players in this matter that could have maintained a claim for the Merlion. With the commencement of litigation if they maintained a claim they would have needed to file an appearance in the proceedings to prosecute any claim they had. Their initial reactions to the arrest are set out below:

Legal person: Voluntary administrators

Interest in the Merlion: As the agents of PMY they had the responsibility for maintaining any legal claim to the boat on behalf of PMY. They set out a claim for the boat as a voidable transaction in the report to creditors.

Potential action: Intervention in the case to claim the boat as a voidable transaction

Reaction: They told our client that they accepted that the Merlion was held on trust by PMY and they did not intervene in the case

Legal person: Defendant

Interest in the Merlion: Up until the arrest the Defendant had possession of the Merlion and claimed title to it pursuant to a transaction with PMY

Potential action: Intervention in the case to claim the boat

Reaction: They filed a conditional appearance in the proceedings and then applied to have the claim dismissed

How is a boat arrested?

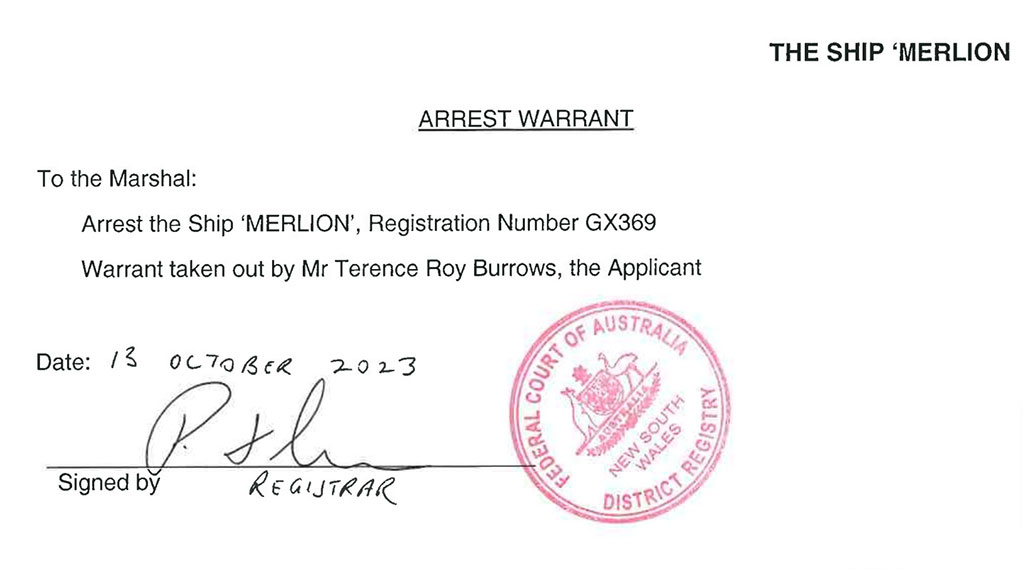

Once the documents (set out above) were processed and checked by the Court the registrar issued an arrest warrant (set out below):

The Court itself executed the arrest, and the court officer charged with this duty is the Federal Court Marshal. The Marshal plays a pivotal role in the enforcement of admiralty law in Australia, and this includes the arrest of boats or cargo. The powers of the Marshal are created by the Admiralty Act 1988 (Cth) and she had the personal responsibility to execute the warrant and then take custody of the boat.

After the issue of the arrest warrant the Marshal attended the Defendant’s private pier on the Gold Coast to take the boat off him. The boat was then moved to a secure location and whilst the proceedings were on foot the Marshal had custody of the boat.

The arrest is contested

One benefit of the arrest procedure is that no notice is given about the arrest warrant to potential defendants. This is something unique to the Admiralty division and it is designed to stop boats being moved offshore (and therefore put out of the reach of the Australian courts). It is also a stronger action than an injunction because the Court itself takes custody of the property rather than just making an order that it not be disposed of. The Defendant, therefore, received notice of the arrest proceedings on the same day that the arrest of the boat was affected by the Marshal.

The Defendant decided to fight the arrest and they began their action by a ‘shot into the hull’. This differs from a ‘shot across the bow’ because the Defendant took aggressive action in an attempt to secure a complete victory that would sink our client’s case. They made a technical application to the Federal Court to dismiss the claim on a jurisdictional basis. The Defendant argued that the claim for ownership and possession of the Merlion was not within the proprietary maritime jurisdiction of the Admiralty Act 1988 (Cth). Our client’s decision to utilise the Admiralty division of the Federal Court to arrest a recreational vessel was not orthodox as the boat was a pleasure cruiser and not a commercial vessel.

The broader basis of the Defendant’s defence was that the transfer of the Merlion (referred to below as Boat 1) was a bone fide transaction. Set out below is an excerpt from evidence adduced by the Defendant (where the Merlion is referred to as ‘Boat 1’):

Each side to the case prepared evidence to support their position and the Court set the application down for hearing in December of 2023.

What was the outcome?

The hearing took place in December 2023, and judgment was delivered in March 2024. The result was that the Defendant’s application was dismissed, and findings made that were broadly supportive of our client’s claim.

The most important issue decided in the judgment was whether the Merlion was being held on trust by PMY and whether our client’s claim was a ‘proprietary maritime claim’ that is covered by the Admiralty Act. The answer was a resounding yes. This was quite a novel use of the Admiralty law because it was not intended to cover recreational craft. The Court found that the claim that the boat as a trade-in was held in express trust was found to be a proprietary maritime claim. The Court also found that our client’s second claim under Barnes v Addy also came within the jurisdiction of the Admiralty Act. The third and fourth claims for constructive trust and conversion were found to be proprietary maritime claims. A claim for conversion is a tort but remains a proprietary claim over a boat. This finding was a strong endorsement of the claim that we formulated but the court went beyond this to find, overall, that our client had a reasonable prospect of success in the case.

The key part of the judgment from our client’s point of view was that the Court found that they had a reasonable prospect of success (overall) in their trust claim:

The judgment torpedoed the Defendant’s claims that he had no notice that the Merlion was held on trust by PMY. This sunk any argument that the Defendant could make that he was a bone fide purchaser of the Merlion for value without notice. This key finding of the judgment is set out below:

You can read the judgment here.

The effect of the judgment was resounding. It sunk the Defendant’s claim that he was a bone fide purchaser of the Merlion and established the court’s finding that our client had reasonable prospects of success.

The Defendant conceded by informing the Court (through their solicitor) that they would ‘take no further part in the proceedings’. As there was no defendant we could move for a default judgment and by May of 2024 the Merlion had been released to our client – free and clear from any claim.

Takeaways

When you enter into a construction contract with a builder if the builder repudiates the contract it is not likely to be a complete loss because the partially build structure sits on land owned by the homeowner. This means that the homeowner can engage another builder to complete the project. On the other hand, the customers of PMY that entered into progress payment arrangements to build a boat in China faced a complete loss when PMY went into voluntary administration.

Customers cannot reliably predict whether a company will become insolvent. They lack access to the company’s financial records, and in PMY’s case, the company was clearly destabilized by the economic effects of COVID-19. Our client traded in the Merlion while PMY was insolvent, unaware that the likelihood of PMY completing the new boat was very low. The take-aways from this case would be:

- Be aware of the difficulties that Australians have enforcing claims in the Chinese mainland. It is difficult to mitigate that risk with contracts.

- When entering into contracts to build boats in Australia consider using the Personal Property Securities Register to list your claim to title to the boat whilst it is under construction. Keep in mind that you will also need a written security agreement to back this up and it may need to be signed by the boatbuilder (not just the boat seller).

Testimonial from our client for our work

Good morning Ben

J and I would like to take this opportunity to Thankyou for your advice and professional services resulting in the return of our boat. There were times when we thought we may have lost but your steadfast resolve encouraged us to stay the course. After 47 years as a business owner I have, amazingly never had to deal with liquidators and if I could wind back the clock I would most certainly have taken a different approach.

Fortunately your advice and that of John guided us to a most satisfactory outcome.

We certainly celebrated with a few wines last night and I hope you did also.

Well done and Thank you Ben.

Regards

T and J

Thank you to our counsel, John Hyde Page

We would like to thank the barrister that acted for our client in the proceedings, John Hyde Page of 5 Selborne Chambers in Sydney. Mr Hyde Page is an experienced barrister who provided invaluable advice and advocacy in this matter.

Mr Hyde Page’s profile is: https://www.5selborne.com.au/barrister/john-hyde-page/