An Important limitation on Deeds of Company Arrangement (DOCAs) – No Ipso Facto Protection

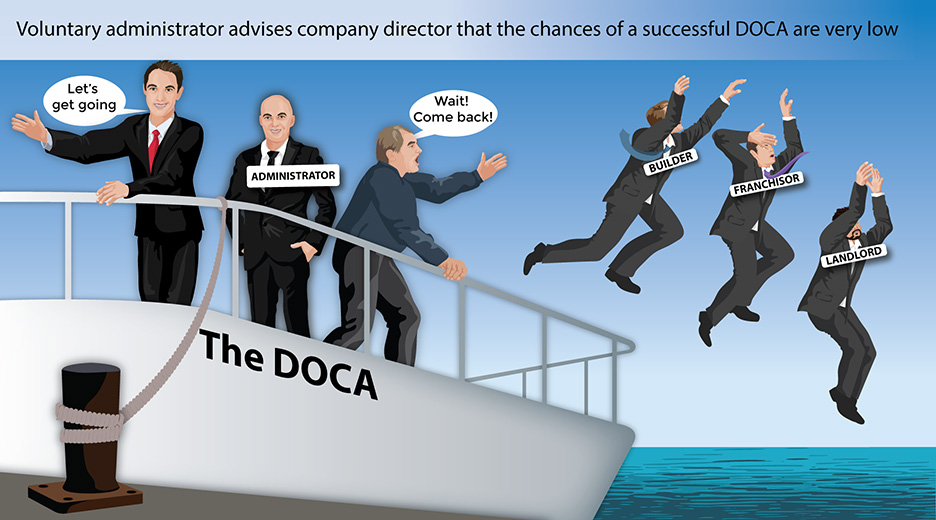

Once the DOCA is being administered, there is no longer a moratorium on ‘ipso facto’ clauses. In short, this allows suppliers, landlords and other creditors with suitable contracts to immediately terminate those contracts on appointment of the deed administrator.

Summary:

Once the DOCA is being administered, there is no longer a moratorium on ‘ipso facto’ clauses. In short, this allows suppliers, landlords and other creditors with suitable contracts to immediately terminate those contracts on appointment of the deed administrator. There are ipso facto protections that apply to voluntary administration but these are withdrawn after a DOCA commences.

Table of contents:

A deed of company arrangement (DOCA) is a binding compromise between a debtor company and its unsecured creditors. The DOCA is the desired outcome of the voluntary administration process. Once a DOCA is agreed to, a deed administrator is appointed to oversee the execution of the DOCA and distribute proceeds to creditors.

An important limitation applies to DOCAs, however. Once the DOCA is being administered, there is no longer a moratorium on ‘ipso facto’ clauses. In short, this allows suppliers, landlords and other creditors with suitable contracts to immediately terminate those contracts on appointment of the deed administrator.

The loss of these contracts is, obviously, a major blow to creditors and the company’s directors who may have hoped to use the DOCA as a turnaround mechanism and revive the company as a going concern.

In this article, we take a detailed look at the DOCA limitation on ipso facto protection.

What is the definition of an ipso facto clause?

An ipso facto clause is a provision in a contract which permits one party to terminate, or enforce other rights in relation to the other party, as soon as a specified ‘insolvency event’ occurs. Usually, these insolvency events include the appointment of a voluntary administrator or liquidator.

These clauses are added by counter-parties to their contracts to protect those companies from the risk of dealing with an insolvent company. By terminating the contract, the company can avoid supplying goods that it believes it may not be paid for (if the debtor company is insolvent and gets wound up). These clauses are commonly included in contracts between head contractors and subcontractors, and master franchisors and franchisees. The clauses are added by counter-parties with significant bargaining power.

As well as mitigating their own risk from future non-performance, ipso facto clauses mean that these counter-parties don’t want to work with insolvency practitioners who will take control of a company once voluntary administration comes into force. They would prefer to have the option to terminate and pass the performance of the contract along to a more reliable counter-party.

The moratorium on ipso facto clauses

Ipso facto clauses are a problem for struggling companies. Any company that is hoping for a restructure or corporate rescue will be stymied by valuable contracts, like lease agreements, being immediately terminated if a formal restructure process is initiated.

It should be noted that ipso facto moratoriums don’t apply to other instances of breach of the terms of contracts. Therefore, counter-parties of a company in a voluntary administration can still terminate for fundamental breaches in performance that relate to common law repudiation and any other standard election that a party not in breach has at law.

These clauses can be particularly devastating in Australia for construction subcontractors and franchisees as significant value is tied up in a small number of ongoing contracts. This makes it almost impossible to preserve the value of the business during a formal restructuring (such as voluntary administration) and attempt to turn it around.

In light of this, an amendment to the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) was introduced, placing a moratorium on enforcing ipso facto clauses in certain circumstances. It came into force in July 2018 and applies to contracts entered into from that date.

Where does the moratorium apply?

This moratorium applies in a select number of cases:

- Voluntary Administration. Until recently, this was the primary restructuring process set out in the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth). In Voluntary Administration, an independent insolvency professional is appointed to the company to try and achieve a compromise with creditors – known as a ‘DOCA’. While the ideal outcome is to turn the company around, in most cases, a voluntary administration ends in liquidation. As a voluntary administration tends to take 6-8 weeks, this is a relatively short reprieve. Shorter, for example, than the US moratorium period of 180 days for Chapter 11 — the main restructuring process available there.

- Small business debt restructuring. This new simplified restructuring process appoints an independent professional to a small business ($1 million or less of debt). The directors remain in control of the company, while the restructuring practitioner helps the directors to develop a plan to restructure the company. The moratorium is particularly beneficial to debtor companies in this ‘debtor-in-possession’ restructuring option, as it allows directors to continue operating the business with as little interruption as possible.

- Where a ‘managing controller’ has been appointed over all or substantially all of the property of the company. A managing controller is a ‘receiver and manager’, or a ‘mortgagee in possession’. That is, they are someone appointed to ensure the realisation of a secured asset, or they are the secured creditor themselves stepping in to recover the asset. As with voluntary administration and small business debt restructuring, this allows business to continue in the company ‘as normally as possible’ while the secured asset is being recovered. Note, the clear limitation, however; this does not apply where the security is over a smaller portion of the debtor company’s property.

- Creditor’s scheme of arrangement. This is a relatively rarely used procedure for a judicially supervised restructure of a company. It is only used in large corporates. It means a binding agreement between the company and its creditors (or a class of c), which modifies the legal rights of both parties. The moratorium on ipso facto clauses, again, gives the company a better chance of surviving the scheme process and continuing to trade.Read more about this option in the Treasury’s recent consultation paper Helping Companies Restructure by Improving Schemes of Arrangement.

There is one common type of restructuring where the moratorium does not apply. That is, a pre-packaged insolvency arrangement (pre-pack) facilitated through the ‘safe harbour’ under the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth). In this ‘safe harbour restructuring’, business assets are transferred from the old company to a new company, for fair market value, with the old company then being wound up. That way, directors can continue to operate the business through the new corporate structure, no longer encumbered by the earlier debt.

As this kind of ‘informal’ restructure is not an act of default, nor an ‘insolvency event’, nor does it become public knowledge, it would not be captured by an ipso facto clause in the first place. Having made this observation a pre-pack has risk associated with it that is separate to dealings with contractual obligations (i.e. allegations of phoenix activity).

Ipso facto clauses do not apply to DOCAs

Once the creditors and a debtor company sign a DOCA, a deed administrator is appointed to oversee the execution of the DOCA. In most cases, the deed administrator is the same person as the voluntary administrator (but need not be).

The moratorium does not apply to the DOCA process. This means that counter-parties can invoke their ipso facto clauses, making DOCAs significantly less effective as a genuine business turnaround option. The only option is for a debtor to apply to the court for discretionary relief (namely under sections 441D, 441H and 444F of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth)).

In short, the benefit of the moratorium goes to the voluntary administrator. They can carry out their task without concern for contracts being terminated. The problem is shifted to the directors who take the reins again once the DOCA has been agreed to. They have no protection against suppliers and head contractors terminating contracts at that point.

In our view, this is a discrepancy which undermines the value of voluntary administration. If there has been no actual breach of contract for non-performance, it seems unreasonable to allow termination merely on the fact of restructuring.

Conclusion

The moratorium on enforcing ipso facto clauses during restructuring processes under the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) is a reasonable restriction on freedom of contract, designed to give distressed companies a fighting chance at turning things around. However, the value of this moratorium for voluntary administration is significantly reduced, given that it doesn’t apply to DOCAs.