Closing down the liquidator’s piggy bank

Table of contents

- Executive summary

- Our client’s background and business: energy, experience and money

- Target business: the lemon

- Immediate problems after soft entry

- Business teeters on insolvency

- The proposed solution: Appoint a voluntary administrator

- The administration process

- Facing litigation by the liquidator

- The solution and stalemate

- Key takeaways

Executive summary

Our client, Paul, got in contact with us because he was frustrated at the approach taken by liquidators who were engaged to undertake a voluntary administration to restructure a newly acquired business.

The key concern was that recoveries of secured debts would be used to fund litigation against our clients. Our clients advanced significant money by way of a secured loan to the company before it was placed into voluntary administration and they therefore had the first ranking security interest.

After the voluntary administration process completely failed, the liquidator raised a potential claim against our clients for insolvent trading in their alleged capacity as shadow directors.

Our response was to cut off the liquidator’s piggy bank by appointing a receiver. This meant that all recoveries were now redirected to the receiver and that the liquidators didn’t have an open chequebook to utilise.

The result was that the liquidators called off their poorly conceived shadow directorship claim and asset recoveries were put on sensible commercial terms. Meanwhile, our clients were able to undertake a rear-guard action to build a new business outside of the external administration process.

The key takeaway is that the clients made a poor decision by accepting “free” advice that a voluntary administration would allow them to restructure an insolvent business. Our advice today would be that clients should consider an informal restructure through the safe harbour from insolvent trading as a first step and only undertake a voluntary administration after thorough due diligence.

Our client’s background and business: energy, experience and money

Our clients were a bit of an odd couple as business partners but they were able to develop a partnership that matched completely different backgrounds. One client was an Australian specialist builder who had 30 years of experience in specialist glass solutions in large office buildings. Our other client was a Chinese entrepreneur who wanted to use his close relationships with glass manufacturers in China to vertically integrate with a commercial glass installer in Australia.

Their objective was to build a commercial glass installation channel in Australia. They decided to grow through acquisition and undertook a process of looking for a mid-sized glass installer that was a market laggard that could be bought for a reasonable price.

Target business: the lemon

Our client’s target was a mid-sized glass installer who had 15 key staff and 20-30 projects on foot at any one time. The business had a long history in the niche commercial construction sector of curtain wall installation, and it had traded since 1991 through a small group of owner-operators. Over time the business had moved into specialist glazing, louvre systems and operable external walls for commercial offices around Australia.

The business was based in a large warehouse in Sydney’s west and it had an established organisation structure with business development, estimating, project and finance staff. At the time there were a small group of directors who had held their roles for a long period and knew the business inside and out.

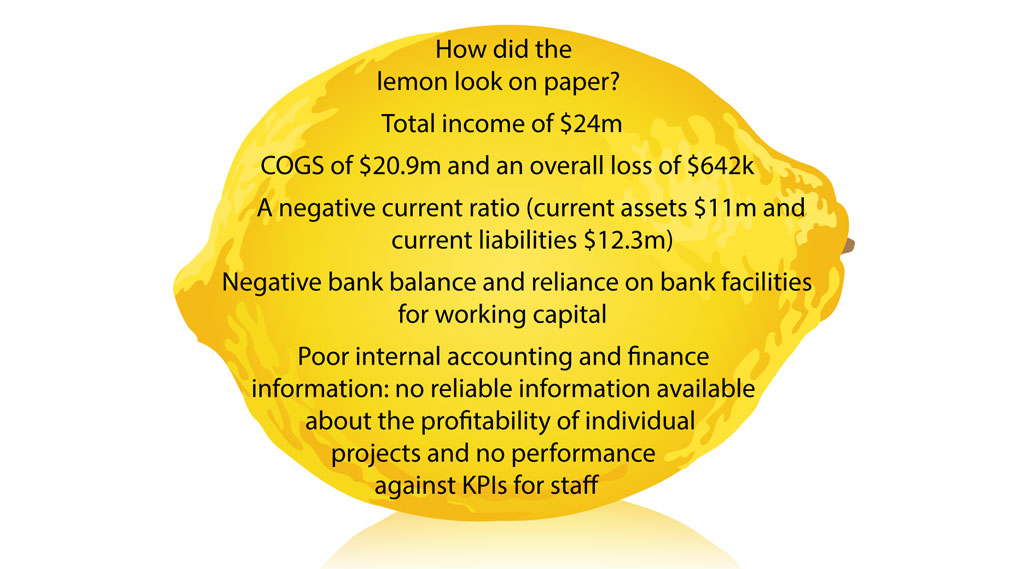

The overall financial position of the business was weak, however. Three-way analysis of the financial results in the year to May 2014 showed the following:

- Total income of $24m

- COGS of $20.9m and an overall loss of $642k

- A negative current ratio (current assets $11m and current liabilities $12.3m)

- Negative bank balance and reliance on bank facilities for working capital

- Poor internal accounting and finance information: no reliable information available about the profitability of projects and no performance against KPIs for staff

Nevertheless, our clients decided that the target was a bargain and they jumped into purchase negotiations. They saw an opportunity to take over a struggling business, inject capital and use their connections with Chinese manufacturers to develop a competitive advantage in pricing.

Ill-fated purchase of curtain wall installer

Rather than enter into an assets-only purchase our clients decided to take a bit more risk and purchase the shares of the outgoing directors. The sweetener was that they got a discounted purchase price and to protect their position they negotiated with the outgoing owners to buy the shares through instalment payments. This would give them the ability to hold back instalment payments if the sellers breached their warranties or covenants under the share sale agreement.

The Share Sale Agreement with the existing owners was signed in June of 2013 and the purchase price was $1.26m for all of the 360,000 issued shares. This purchase price was agreed to be paid in instalments from January to June of 2014 and it was a term of the agreement that the outgoing owners had to hand over operational oversight of the business before receiving payment of the total purchase price. At first blush the terms of purchase were quite favourable to the purchasers because they obtained a hand in the business before paying for it. On the other hand, in the light of events that followed it became clear that the outgoing owners were looking for a parachute at any cost and our clients went through a painful process that ultimately lead to the collapse of the company.

It was a condition of the Share Sale Agreement that a key director was required to stay on board as an appointed director until the Share Sale Agreement had completed.

Unfortunately, there were minimal vendor warranties under the Share Sale Agreement but a key warranty was that tax liabilities were required to be disclosed. Having only one vendor warranty was a mistake because it meant that our clients had no right of recourse against the outgoing owners for the poor state that the company was in. On the other hand, this was negotiated by the outgoing owner’s lawyers because they probably understood that the business was distressed.

Our clients did undertake some sensible asset protection though, including:

- Using a nominee company with a fixed trust to purchase the shares

- Requiring the owner to stay on board as the appointed director

- Installing one of their staff as a manager to oversee the business

- Installing a chartered accountant to oversee the accounting function

The target company’s last financial year accounts before acquisition (30 June 2013) didn’t show how truly precarious the company’s financial position was. It’s income statement showed:

- Income $21m

- Less cost of sales $16.4m

- Gross profit = $4.6m

- Less expenses $4.8m

- Loss = $200k.

The target company’s 30 June 2013 balance sheet showed positive owner’s equity:

- Current assets $6.7m

- Non-current assets $789k

- Current liabilities $5.5m

- Non-current liabilities $420k.

When the target was acquired, it was implementing a business plan that was prepared in September of 2013. The company predicted a profit for year ended 30 June 2014 of $2.7m before tax with closing cash position on the balance sheet of $1.1m.

Based upon cashflow forecasts our client prepared, they formed the view that they would need to inject $600k into the business to meet future working capital needs. This turned out to significantly underestimate how much was required to be invested in the company to keep it afloat.

The outgoing owners’ business plan budgeted an overall sales target of $37m and this represented a large increase on the previous financial year’s result (76%). But the business plan was vague on details of how the budgeted targets would be achieved and there were no marketing tactics, operational investments or staff restructures proposed. Critically, the business plan stated that it required significant financing to achieve these objectives and this included invoice financing (i.e. a debt factoring facility) of $3.2m and a bank facility of $2.2m. The cost of finance wasn’t included in the projections and the calculations for this financing were not part of the plan or explained with any particularity. In retrospect, this business plan was a puff piece to attract potential buyers that didn’t end up being reliable other than predicting that significant financing would be required for the company.

Immediate problems after soft entry

Our clients’ strategy was to have a ‘soft entry’ into the company after the Share Sale Agreement was entered into. The soft entry would mean that:

- Our clients themselves didn’t take over the day-to-day running of the business;

- The former owner would remain as the sole director and fulfil his duties to run of the business;

- A manager who was reporting to our clients would be installed to get a handle on what was going on in the business; and

- An independent accountant was engaged to monitor the company’s financial position and report back to our clients.

From Day 1 the quality of the business our clients acquired was shaky, the following problems jumped out:

- The company had been overstating the value of work-in-progress of its construction projects

- The company had been overstating the value of stock held (i.e. the curtain wall that was its signature product)

- The company was overstating its profitability

- The company was overstating the progress to completion of its projects

- The company had failed to disclose a tax liability of about $300k

- The company’s bank was furious because it wasn’t consulted about the share sale transaction and it threatened to terminate the company’s bank facility and call in the entire bank debt owed

The most immediate problem for our clients was that in August of 2013 the company’s bank gave formal notice that the company was in breach of its covenants. It was a covenant that if there were any changes to ownership or a directorship this would be notified in advance (but it was not). Also, the bank called a breach for interest rate cover because the bank received the 30 June 2013 financials that showed that the company had made a loss. The bank issued a series of demands including being provided with an updated business plan, a cashflow forecast and a diagram of the current corporate structure.

Our clients hit the panic button and got to work. They complied with the bank’s demands for information and also sold a subsidiary business for $654k to raise working capital and streamline operations.

But, the profitability of the company deteriorated throughout the financial year and this caused cashflow to become pressured. The company’s 30 June 2014 financial accounts showed:

- Income $28.1m

- Less cost of sales $26.7m

- Gross profit = $1.4m

- Less expenses $5.1m

- Loss = $3.7m

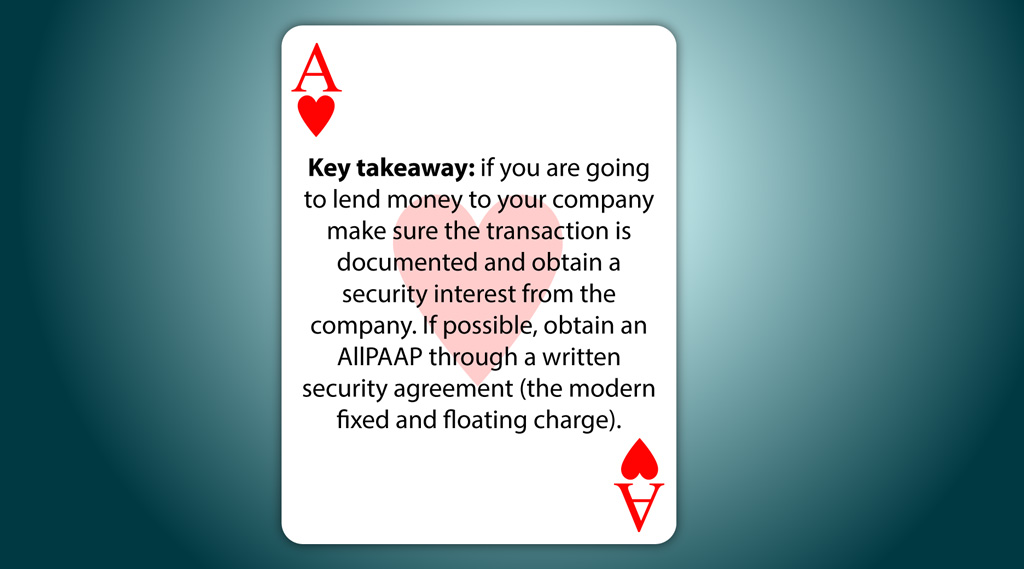

It became clear over the course of 2014 that, unless working capital was contributed to the company (by the owners or from a financier), the company would go into insolvency. Our clients decided to lend the money to the company themselves and advanced $2.1m to the company by way of a loan. Sensibly, our clients documented the loan and obtained a security agreement from the company. This meant that they obtained an All Present and After-Acquired security interest in the company. By that time the bank had lost confidence in the company and our clients were required to take over the bank’s position as principal financier, they therefore had a first ranking security interest.

In September 2014 our clients started to shop around for financiers for the company. They quickly realised that obtaining external finance would be difficult because of the company’s poor financial position. One financier they contacted asked for the following information:

- “Updated WIP details

- Details of contracts on foot

- I’d like to get behind in more depth what was the cause of the loss than decrease in margin, is it still happening or is it a “one off”!

- The margin last year was 22%, this year 5%, where do they forecast it will be next year, do they have a cashflow forecast for me to review – it will be required

- Consultancy fees increased from $200k to $380k, who receives this and what consulting was provided”

The problem was that when they got a handle on the profitability of construction jobs on foot, they ascertained that the company’s jobs were not profitable and that they would need to ride out the current contracts and increase prices in new contracts. This would take some time so by October of 2014 our client started to shop around for a more expensive finance solution – a receivables finance facility. This became an indication of their desperation.

By December of 2014 our clients decided that they couldn’t salvage the situation so they decided to call it quits by terminating the Share Sale Agreement. But they still had significant money invested in the company and they looked for a way to recover value.

Business teeters on insolvency

The legal definition of corporate insolvency is that a company isn’t able to pay its debts when they fall due and payable. Further, actual insolvency is not just a temporary illiquidity, it is where a company has an endemic shortage of working capital.

As part of the soft entry into the business, our clients had installed a manager to get a handle on the business with a view to having him take over as general manager sometime. The manager faced daily battles because projects were facing delays and the head contractors (i.e. the customers) were furious. This caused problems with obtaining progress claim monies, which was the cause of the deteriorating financial position of the business. By the end of 2014 the manager had quit and, as a direct cause of the acquisition, he had a nervous breakdown.

The former owner who remained as the sole director of the company called in sick one day and never came back. This meant that the company didn’t have a working director and the business became headless.

The proposed solution: Appoint a voluntary administrator

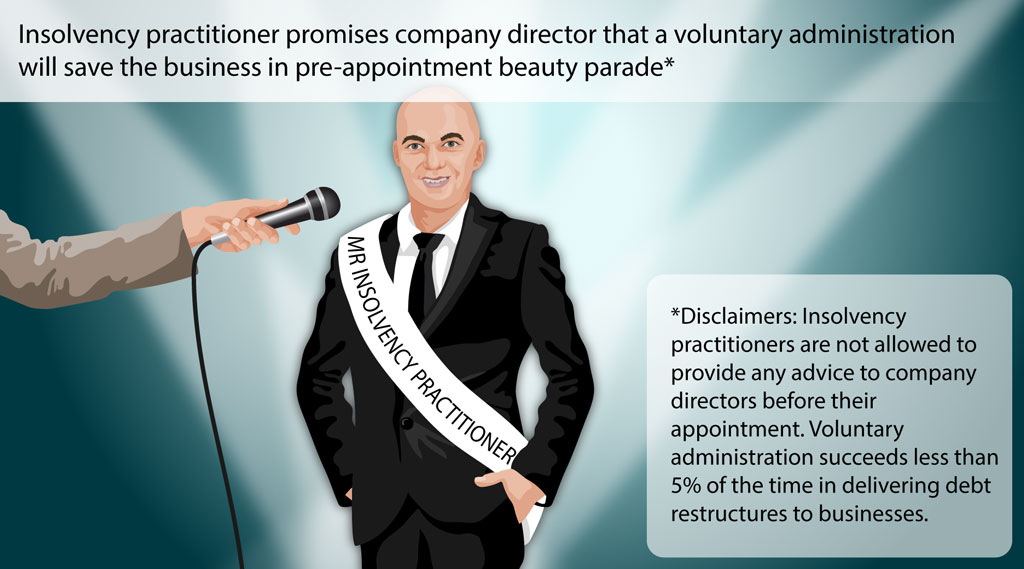

Our clients took the next step of organising meetings with financiers, finance brokers and insolvency practitioners to work out what to do next. It became a beauty parade and rather than engage a specialist turnaround firm, they obtained a lot of “free” advice from professionals that were looking to sell their “products”. They say that if you ask a barber for advice then he’ll recommend that you get a haircut. Ultimately, our clients accepted the advice from an insolvency practitioner that they should initiate a voluntary administration (through their AllPAAP security interest) and then restructure the company through a deed of company arrangement (DOCA).

The problem was that no one was engaged as a consultant to represent the clients themselves (until Sewell & Kettle was engaged later) so the beauty parade that the clients initiated was a sales pitch rather than a due diligence exercise by professionals subject to a fiduciary interest.

The insolvency practitioner that recommended a voluntary administration is actually barred from providing meaningful advice to company directors before they take any appointment as voluntary administrator. Australian law regards this as an irredeemable conflict of interest because the voluntary administrator is required to act in the best interest of creditors (not the directors or owners of the business). Insolvency practitioners are limited to discussing insolvency options with company directors to preserve their independence. The writer disagrees strongly with this policy and believes that insolvency practitioners should be allowed to undertake due diligence before taking appointments and they should also be required to provide meaningful advice to directors about the prospects of success of whatever course they recommend.

Our clients decided that, rather than contribute more money to the company or obtain expensive finance, they would appoint voluntary administrators in December of 2014 with a view to restructuring the company. Their objective was to propose a debt compromise to creditors and obtain a settlement through the deed of company arrangement procedure.

The administration process

The voluntary administration commenced in December of 2014 and then all hell broke loose.

The sole director of the company completely ghosted the voluntary administrator and wouldn’t help them at all. This made the DOCA process problematic because DOCAs are usually proposed by company directors and voluntary administrators need close support from company directors to trade businesses. Voluntary administrators are very adverse to taking any trading risk because they are personally liable for any trading shortfalls during a voluntary administration. This means that unless a voluntary administration is cash flow positive, they will terminate the trading operations and shutter the business.

When the voluntary administrators were appointed there was close to $1m in the company’s bank account and although this was secured, our clients decided to let the money stay in the bank account and be used for the administrator’s professional costs and expenses. They wanted the process to be well funded so that the voluntary administrator could put together a restructuring plan.

At the date of the appointment of the voluntary administrator the company had 39 construction projects on foot but by the end of the administration all these had been terminated by head contractors. Head contractors generally don’t like to work with voluntary administrators and they would prefer to take the projects out of the hands of subcontractors who go into administration and give them to others.

The entire purpose of the voluntary administration, a DOCA proposal to restructure the company, was not feasible because:

- The sole director had ghosted the voluntary administrators;

- The head contractors terminated all projects on foot;

- The unsecured creditors were furious because they knew they would be likely to receive no meaningful return (i.e. be out of the money); and

- The voluntary administrators had no stomach for continued trading.

If our clients had undertaken due diligence from an experienced insolvency lawyer or turnaround professional before the appointment it would have been obvious that the voluntary administration appointment would be seen as tantamount to a liquidation and it would result in a complete collapse of the business. Our advice would have been that the clients should look at a receivership or appoint a professional director to undertake a safe harbour restructure.

The creditors were angry because the total of the proofs of debt lodged was $34m and any DOCA that was put forward would only be a fraction of that amount. It would be likely that most of the deed fund would have been swallowed up by professional fees and expenses.

Another bad sign was that the voluntary administrators had forensic accountants from their firm working on the voluntary administration from day 1. This is not a good indicator because the only purpose of appointing the forensic accountants would have been to obtain evidence that could be used later for an insolvent trading claim.

Predictably, the voluntary administration failed and the company was placed into liquidation in January of 2015. At that time, the administrator became the liquidator and was then legally required to cease trading and wind up the business.

The only person getting an upside from the failure of the voluntary administration was the administrator because they had a feast of fees. This is not a criticism of the voluntary administrator because it is the role they have and there is no suggestion that they did not thoroughly execute their duties. This is meant to criticise the system of corporate insolvency in Australia that insolvency practitioners are required to follow. The writer is sure that voluntary administrators would appreciate more scope to provide pre-appointment advice, undertake pre-appointment transactions and then take a more entrepreneurial approach to a restructuring.

The liquidator was able to make financial recoveries through selling the plant and equipment of the company and getting funds from head contractors for progress claims and cash retentions. As at April 2016 the scorecard of actual and potential recoveries is below:

- Recoveries made: $687,285

- Likely recoveries: $1,397,130

- Further investigation required: $2.54m

- Recoveries unlikely: $4.99m

- Total potential debtor and retention recoveries: $9.6m

Other assets realised:

- Stock: realised $186k

- Plant and equipment: $115k

The employees of the company were largely covered by the Federal Government via the FEG scheme, although they were owed $1.2m in entitlements.

Facing litigation by the liquidator

After the company was placed into liquidation the clients started a rear-guard action to recover business value. As the company was already in liquidation this was not phoenix activity because there were no asset or business transfers before the company was wound up. What the clients did was reach out to head contractors and former employees with a view to starting a streamlined curtain wall business that would take over the terminated subcontracts formerly undertaken by the company.

The liquidators didn’t look too favourably on our clients and they may have developed a theory that they were shadow directors of the company and that they should be liable for insolvent trading. In September of 2016 the liquidators started formal examination proceedings against our clients to test their theory and obtain evidence and oral admissions.

At that time our clients became incredibly frustrated and they engaged Sewell & Kettle to represent and advise them. Their view was that they weren’t shadow directors and that the company didn’t trade whilst insolvent because they advanced $2.1m to prop it up. Once they decided they wouldn’t support the company anymore they used their powers as a secured creditor to appoint a voluntary administrator. They felt that the voluntary administrator was conflicted, firstly because of their pre-appointment advice to use voluntary administration to restructure the company, secondly their work to blame them for the insolvency and use of secured monies to fund this work, and third, their feeling of powerlessness to deal with the situation.

Whilst there is no suggestion that the voluntary administrators acted improperly, it would be fair to say they “charged like a wounded bull”. Set out below are actual figures for remuneration and a comparison with actual realisations.

| Total remuneration 8/12/2014 to 7/10/2016 | $1,191,062.25 |

| Total effective realisations 8/12/2014 to 7/10/2016 | $1,714,834.22 |

| Remuneration as a percentage of effective realisations | 69% |

It is clear that neither the clients, the company’s employees, the company’s head contractor clients or the company creditors got much financial benefit out of the voluntary administration process.

The solution and stalemate

After the liquidation commenced, our clients independently courted the company’s head contractors and staff and managed to lure a significant portion of the goodwill of the business back to themselves. This is not illegal but it is a pity that the voluntary administration process was not well suited to accomplishing a debt restructure so that the outcome wouldn’t have been so haphazard. Overseas materials supplier relationships gave our clients a competitive advantage in pricing and they wouldn’t have the baggage of the liquidated company to deal with by setting up a new company.

Our clients regret going through the voluntary administrator process and in retrospect they would have done the following:

- Bought the business via an Asset Sale Agreement

- Taken over day to day running of the business and renegotiated contracts with head contractors

- Implemented KPIs for all staff and terminated unproductive and toxic staff

- Rescheduled contracts to ensure that promises could be met

At the stage of appointing voluntary administrators, it would have been better for them to appoint a private receiver and allow the creditors to appoint their own liquidator. This would have meant that the asset sales and recovery of debts could have been undertaken by a privately appointed receiver who reported to our clients and remitted funds directly to them (after priority claims to employees were satisfied). Further, they could have negotiated to take over contracts from the receivers or at least bought plant and equipment and stock.

The April 2016 report to creditors issued by the liquidator was damning. The report stated that the liquidators were confident that company had traded insolvent for at least 12 months before administration started in December of 2014.

In September of 2016 the liquidators started examination proceedings to obtain books and records and also to undertake an inquisitorial examination of our clients.

Our solution was to immediately appoint a company receiver of our choice over the top of the liquidator. We recommended this to stop the conflict of interest that the voluntary administrator had. The conflict of interest was that he was simultaneously investigating our clients whilst collecting progress claims and cash retentions that were secured debts (and therefore owned by our clients). The war chest of funds the liquidators had built up was at risk of being used to investigate and sue our clients.

After we appointed the receiver, we had an immediate victory. The liquidators backed off on the examinations and were forced to look into alternative methods of obtaining litigation funding. We have verified this through the publicly available minutes of a meeting of the committee of inspection of the liquidation where it recorded:

“The receivers and managers will not fund the liquidators to continue with the examinations in respect of potentially voidable transactions and insolvent trading so it is likely (unless alternative litigation funding is sourced) that these examinations will not proceed.”

The next step we undertook was to take the battle to the liquidators by starting a review of their fees. We wrote to the liquidators to demand an explanation for their charging. At that time, Justice Brereton in the NSW Supreme Court was undertaking a quest against overcharging liquidators and it looked like some sense would be put back into liquidator professional fees and liquidators would be stopped from loading up on liquidations that had assets.

We advised our clients about recent decisions in the NSW Supreme Courts that emphasised the need for a liquidator’s fees to be proportionate to realisations. Cases on point were:

- In AAA Financial, Justice Brereton of the NSW Supreme Court found that 20% of assets realised was appropriate level of remuneration;

- In Hellion Protection Justice Brereton of the NSW Supreme Court found that 10% of assets realised plus 5% of GEERS was appropriate remuneration;

- In GJP Investments, Justice Brereton of the NSW Supreme Court found that 5% of net realisations was within an acceptable range for approval;

- In Sakr Nominees, Justice Brereton of the NSW Supreme Court found that remuneration in the order of $200,000 being 5% of net realisations was acceptable;

- In Gramarkerr, Justice Brereton of the NSW Supreme Court found that remuneration in the order of 12.5% of gross realisations was disproportionate and that 10% of the first $100,000 of recoveries and 5% of the balance of recoveries was appropriate; and

- In Primespace Property, Justice Black of the NSW Supreme Court enunciated the opinion that Brereton J’s decisions, as set out above, are not limited in application to small liquidations. The objector to costs, in that case, however, did not make a submission that a percentage of recoveries methodology was appropriate, no doubt because of the large recoveries in the liquidation made in the order of $15m. The objector made objection on the basis of categories of remuneration claimed.

But Sakr Nominees was appealed to the NSW Supreme Court of Appeal as a test case and Justice Brereton’s proportionate billing principles were overruled.

The end result was that the liquidators didn’t commence proceedings to sue our clients for insolvent trading as shadow directors. It may have been because they didn’t have funding or, alternatively, they accepted our client’s argument that they weren’t actually shadow directors. Our firm took robust action to put our clients’ interests first and called the liquidators to account for their billing.

*We have consent from the clients to write this case note and at the date of publication the statute of limitations period has expired on any potential civil litigation against our clients.

Key takeaways

- Mid-sized construction companies can quickly go insolvent because of working capital requirements – they need to keep an eye on KPIs and focus on the profitability of jobs.

- Company directors should undertake due diligence before commencing a voluntary administration by using an appropriately qualified professional adviser who is their fiduciary rather than engage in a beauty parade of insolvency practitioners.

- Asset protection – use a sale of business assets transaction rather than a transfer of shares if the business is financially distressed.

- When acquiring any mid-sized construction company get on top of business metrics quickly upon acquisition and focus on the profitability of projects.

- Take insolvent trading allegations seriously and ensure that board minutes are recorded and financial information is retained – today our clients could have used the safe harbour from insolvent trading to undertake a restructure rather than going into voluntary administration.

- Be careful of bait and switch tactics from insolvency practitioners – liquidators act for creditors not company directors so they have no duty to provide high quality advice.

- Be careful of phoenix activity allegations – in this case our clients took over the construction contracts and former employees after the liquidation commenced but if they did so before liquidation, they would have been accused of phoenix activity and potentially sued for creditor-defeating dispositions.

- Hire a competent insolvency lawyer to assist with the commencement of a voluntary administration to a avoid bait and switch and to provide sensible advice.