What is the role of solicitors in the restructuring of insolvent small or medium-sized businesses today?

In article:

- Introduction

- The Standard Insolvent SME That Consults Solicitors

- Voluntary Administration Success Rates Are Very Low

- Move away from voluntary administration to immediate liquidation

- The role of lawyers isn’t defined

- The stigma associated with insolvency in Australia

- A pre-pack insolvency arrangement is a legitimate option – in some cases

- The tools lacking in a voluntary administration scenario

- Our role as lawyers: Rights based advice for SMEs

- Root cause analysis – get out of the ivory tower

- Conclusion

The COVID-19 economic meltdown has already led to some quick changes to Australian bankruptcy and insolvency law. However, as the basic tools for dealing with insolvency remain the same, it is worth looking at the general regulatory landscape and asking what is the role of lawyers? And what should that role be?

Introduction

The existing mechanisms in Australia for the formal restructuring of insolvent small-to-medium sized enterprises (SMEs) are not fit-for-purpose and provide few benefits for SMEs, creditors or the broader economy. The principal formal restructuring process, voluntary administration, has an extremely poor success rate: In most cases the return for creditors is lousy and the business is wound up anyway. The other formal re-structuring process in Australia, a court-supervised ‘scheme of arrangement’, is time-consuming and too expensive for SMEs and therefore rarely utilised.

With largely unsuitable formal restructuring mechanisms, this raises the question, which informal restructuring mechanisms are appropriate? In this piece, we suggest that whatever answer is given, solicitors have an important role to play.

The Standard Insolvent SME That Consults Solicitors

The typical insolvent SME that seeks advice from its accountant or solicitor is small and has limited assets on its balance sheet. The latest statistics from Professor Jason Harris’ ASIC Report 647 for FY18-19 regarding typical company liquidations are:

- Employees: 78% of SMEs have fewer than 20 and 62% have 5 or fewer

- Total assets: 78% of SMEs have $50,000 or less and 85% have $100,000 or less

- Total debts: 62% owe less than $250,000 to unsecured creditors

- Books and records: 45% have adequate books and records

- Estimated returns to creditors: 92% produce no return to unsecured creditors.

These statistics paint a sorry picture: On wind-up, nearly half of SMEs demonstrate poor financial management and the majority have few assets. And while they owe moderate amounts of debt, most unsecured creditors get nothing. Many of these businesses might have been saved, but the formal insolvency and restructuring regime has not facilitated this happening.

Voluntary Administration Success Rates Are Very Low

In voluntary administration, an independent professional is appointed to take control of the company from the directors and to facilitate creditor agreement to a ‘Deed of Company Arrangement’ or ‘DOCA’. The Productivity Commission’s 2015 Report on insolvency reform found that the current insolvency regime does not effectively promote restructuring due to the high failure rate of voluntary administration. Only 13% of insolvent companies appoint voluntary administrators and, of those, the prospects of a successful DOCA are very low.

Recent research by Professor Jason Harris found that, over a long-range sample, 29% of administrations entered into a DOCA. The percentage of successful DOCAs that delivered long term trading enterprises is unknown, but believed by the author to be low and something in the order of 25% of DOCAs.

The depressing probability of a successful Voluntary Administration can be broken down as follows:

- Insolvent companies utilising Voluntary Administration (13%), multiplied by

- Estimate of DOCAs being approved by creditors (29%), multiplied by

- Estimate of successful DOCAs (25%)

The resultant insolvent companies successfully restructuring through voluntary administration? 1%.

Partly because of the poor success rates of the procedure, lawyers and the wider public see the voluntary administration process as a “glorified liquidation”, rather than a robust formal process for restructuring.

This is quite different than the perception of the ‘Chapter 11’ process in the United States and other debtor-in-possession regimes around the world. In the Chapter 11 process:

- The Court supervises the company’s attempt to negotiate a plan to re-organise the business;

- The existing debtor remains in control of the business;

- There is a moratorium on creditor proceedings against the debtor company;

- Financing and loans can be acquired on favourable terms through giving new lenders first priority on earnings;

- With the Court’s permission, the company is allowed to reject or cancel contracts.

Chapter 11 does not seem to carry the same stigma with businesses, lawyers or the general public as voluntary administration does. One commentator, Professor Nathalie Martin, suggested that “in some industries, like the high-tech or dot-com industries, going through a business failure actually can be seen as a badge of honor, proof that the entrepreneurs were willing to take the kinds of risks necessary to fuel capitalism.”

Move away from voluntary administration to immediate liquidation

Voluntary administration started in 1993 as an innovative alternative to liquidation and receivership. Over the last 20 years, however, the popularity of the mechanism has deteriorated sharply.

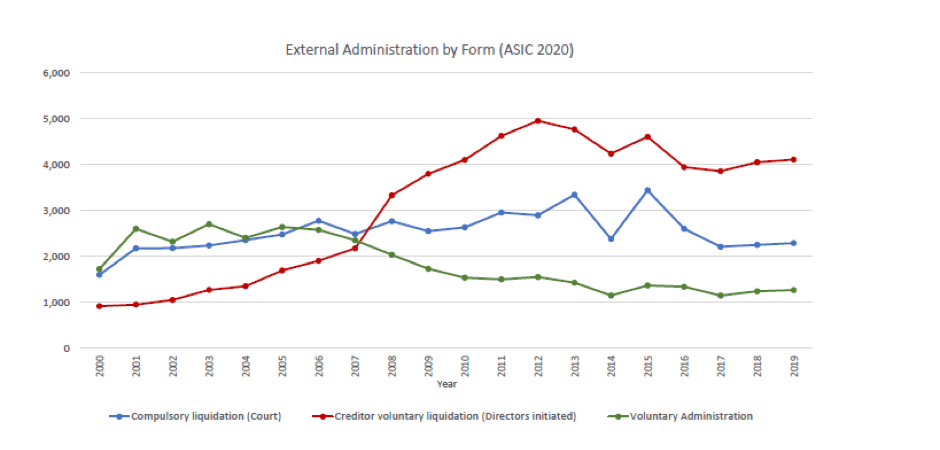

Voluntary liquidation up and voluntary administration down for SMEs

The above chart shows the inversion of the use of voluntary liquidation by directors (Creditors Voluntary Liquidations of ‘CVLs’), and voluntary administration over the last 20 years. What has caused this? The likely contributors include:

- phoenix activity – the often illegal practice of transferring business assets into a new company for less-than-market consideration;

- high failure rates of failure of voluntary administration; and

- the streamlining of CVL appointments by directors.

The reality is that many appear to have given up on voluntary administration as a useful mechanism for formal restructuring of SMEs. Aside from the reputational effects of going into voluntary administration in Australia, creditors are aware that they are unlikely to get a return so will often use their power to vote down a restructure (i.e. they are ‘out of the money’).

The role of lawyers isn’t defined

Given that lawyers, perhaps, have good reason not to be involved in voluntary administration, what role might they play in the insolvency process?

Insolvency practitioners have a clear mandate for their role and obligation to maintain independence. They can properly advise directors of insolvent SMEs that they are illegally trading whilst insolvent, and that the insolvency practitioner can take a voluntary administration appointment to commence formal restructuring.

Unfortunately, the role of lawyers in an insolvency or potential insolvency is not so easily defined. Added to this is a tendency of lawyers to feel uncomfortable in providing advice with an element of financial calculation.

There is an opportunity for lawyers to assert themselves in the pre-insolvency role. Their possession of legal professional privilege, duties to clients and established role as a trusted advocate, place them in good stead to advise company directors. The insolvency practitioner, by contrast, lacks those duties and privileges toward company directors. They have no legal duty of disclosure or other duties towards directors such as avoiding conflicts and acting in the client’s interests.

Furthermore, if an insolvency practitioner takes a formal appointment, their duty may be to investigate, report and commence litigation against the directors.

The stigma associated with insolvency in Australia

The Productivity Commission found in 2015 that there was an industry-wide view that Australia lacks a turnaround culture. The author’s view is that this has created a ‘Darwinist mentality’ in corporate insolvency that ignores the needs of SMEs. Rather than encourage SMEs towards compliance and viability, they are pushed into evasion and liquidation.

By contrast, in the United States, the current President has utilised the Chapter 11 insolvency regime four times to restructure his businesses (Trump Taj Mahal in 1991, Trump Plaza Hotel in 1992, Trump Hotels and Casino Resorts in 2004 and Trump Entertainment Resorts in 2009). President Trump has been able to frame his business experience as being part of a winning mindset.

“I’ve never lost in my life” – Donald Trump

Consider the Australian case: it is inconceivable that an Australian politician would be elected to high office when companies they managed had unpaid subcontractors and employees. Liquidation and voluntary administration are viewed equally as failure and incompetence in Australia. In practice, voluntary administration is not viewed as an opportunity to restructure but a preliminary step in the termination of the life of the business.

A pre-pack insolvency arrangement is a legitimate option – in some cases

The lawyer’s ethical and professional obligations are their value proposition: The client can rest assured that the lawyer has provided full disclosure of their fees, that the lawyer is focused on their interests and that their communication has strict protections under the law. There is no ulterior motive other than offering competent advice within the bounds of the law and their ethical obligations.

The current insolvency industry ‘bad-guys’ are advisers that help clients undertake “phoenix activity” As mentioned, this involves resurrecting a business by transferring its assets from an old company to a new company, for less-than-market-value consideration. To further guard against the undervalued transfers of assets, the government has made ‘creditor-defeating dispositions’ illegal under section 588FDB of the Corporations Act 2001. This means that clumsy or fraudulent restructuring may give rise to criminal and civil claims against directors and their adviser from a future liquidator.

In contrast to illegal phoenix activity, there exists the pre-pack insolvency arrangement. Under these arrangements, there is usually a transfer of assets from an insolvent company to a new company, for valuable consideration. This is still legal in Australia and the consideration proffered is usually the future payment of employee entitlements and key supplier debts. The result is likely to be better for creditors as a liquidation would likely result in the payment of liquidator fees but no return to creditors.

The tools lacking in a voluntary administration scenario

Unlike many overseas jurisdictions there are no mechanisms in place for insolvent companies that preserve a role for management, allow pre-pack sales, provide for preferential financing or extended moratoriums. This means that there is less flexibility for formal restructuring in Australia. This is counter-productive as, in this author’s opinion, it ultimately pushes SMEs towards phoenix operators who encourage fraud or other illegal activities: For example, hiding assets and destroying books and records so that any pre-liquidation asset transfers are hidden.

The table below from Altman, Hotchkiss and Wang’s 2019 work on Corporate Financial Distress, Restructuring, and Bankruptcy lists the basic tools for formal restructure and compares the United States to Australia.

| Country | UK | USA | Australia | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Creditors have unilateral rights to seek court protection or appoint parties to manage the business in default | YES | NO | YES |

| 2 | There are restrictions (creditor consent or insolvency test) to enter court proceedings | YES | NO | YES |

| 3 | Officers and directors face liability for operating the business while insolvent | YES | NO | YES |

| 4 | The debtor continues to manage the firm pending the resolution of the case | NO | YES | NO |

| 5 | Secured creditors can seize their collateral, i.e. there is no “automatic stay” | YES | NO | YES |

| 6 | Secured creditor rank first in priority (above other creditors such as government or workers) | YES | YES | YES & NO |

| 7 | The debtor can obtain post-filing super priority credit | NO | YES | NO |

| 8 | There are no provisions for cooperation between domestic and foreign courts | YES | YES | YES |

The salient points are that that while a company is in voluntary administration, it can’t borrow, and the management of the business is removed. Furthermore, directors can only initiate voluntary administration if they are insolvent. Therefore, the result is usually a chilling effect that is interpreted by the market as the equivalent of a liquidation.

Our role as lawyers: Rights based advice for SMEs

The professional duties and legal professional privilege that lawyers hold gives them a unique position to advise in the case of insolvency, relative to accountants or insolvency practitioners. Our role as lawyers is to provide rights-based advice to proprietors of businesses. Unlike other professionals and service providers, lawyers don’t (or shouldn’t) provide one-size-fits-all products or solutions to a client’s situation. Rather, lawyers adapt their advice to the unique situation at hand and are required to consider what is genuinely in the client’s best interest.

The key take-aways for lawyers for their role are:

- Lawyers must be critical thinkers – the ability to ‘think outside the box’ and offer tailored advice is what distinguishes us;

- Lawyers act for proprietors – we give rights-based advice about property and its owners and are protected by legal professional privilege;

- Lawyers advise against fraud and recommend up-to-date financials and the lodgement of tax returns;

- Lawyers undertake due diligence by testing key assumptions such as title to assets before appointment of voluntary administrators;

- Lawyers negotiate with stakeholders and insolvency practitioners on behalf of proprietors – they are advocates.

Lawyers can be distinguished from other service providers that assist insolvent SMEs:

- Insolvency practitioners: They are less interested in informal restructuring due to the possibility of a conflict of interest and the possibility of being scrutinised in future for pre-appointment advice given.

- Private practice accountants: They are usually the first port-of-call for struggling businesses, but their business model makes it more difficult to offer tailored advice. As they have 100 other clients, like dentists they are more likely to focus on the wealthiest clients, rather than those in the worst financial position. They may see insolvent clients as time-consuming and have limited opportunity to delegate tasks.

- Phoenix operators: They use fraud and dishonesty as their methodology and are not reliable fiduciaries: Insolvent SMEs cannot count on a phoenix operator to act in their interests.

Root cause analysis – get out of the ivory tower

In order to serve their clients, lawyers need to be able to talk about and analyse the root causes of client insolvency. When the media reports on SME insolvency, the most common cause referred to is ‘poor cash flow’. This is incorrect, however: Poor cash flow is a symptom, not a cause of insolvency.

The well-known causes of insolvency are sometimes divided into primary and supporting factors by Argenti:

Primary factors of insolvency:

- Poor management. In too many cases the directors, owners and managers of SMES are driving the trucks or laying the bricks. They are not devoting sufficient time (and may not have the expertise, experience or knowledge) to competently manage the business.

- Poor change management. All SMEs face changes from time to time. Whether these are regulatory changes, changes in the business environment (e.g. extra competition) or technological changes, these changes can quickly deteriorate margins if businesses are incapable of responding to change.

- Overtrading. This occurs when a business extends itself too far and grows too fast, and it runs out of working capital.

- Disproportionate investment in big project. This is a relatively large project without revenues that diverts attention of managers as well as cash flows.

Supporting factors of insolvency:

- Lack of up-to-date accounting information. If you can’t measure it, you can’t manage it.

- Poor risk management of predictable events. Some events (like the current pandemic) are difficult to predict, but other events are more likely to occur from time to time, such as a social media catastrophe or an ‘anchor’ client leaving.

- ‘Creative accounting’. Sometimes the business proprietor relies upon a spreadsheet they created for their financials. Perhaps they have been too generous with deductions or optimistic with expected receipts. Without reconciled financial statements, they may mislead themselves about their true financial position.

This author adds that for SMEs (in contrast to large corporates), there is an extra factor to consider. As the business becomes the ‘dominion’ of the proprietor, their personal problems more heavily impede business operation. Personal difficulties such as mental illness, alcohol or drug abuse, relationship breakdown, family issues or divorce can affect every facet of the business. It might be surmised that this is one of the reasons why the construction and transport sectors, where owner-operators and gruelling work hours are the norm, have relatively high rates of insolvency.

Conclusion

The key existing mechanism for formally restructuring a company in Australia doesn’t work. Very few voluntary administrations result in the business continuing as a going concern. This means that informal restructuring mechanisms, such as pre-pack insolvency arrangements, are the best bet for the survival of SMEs.

Lawyers have tended not to assert themselves in this process. But they should – their fiduciary duties, legal professional privilege and client/proprietor-focused approach makes them well-suited to this task.