The Complete Guide to Trading Trusts for small and medium-sized business

A trading trust is a trust over goodwill and business assets with the trustee being the legal person responsible to creditors. A trading trust is usually a discretionary trust whose trustee is a company, that is used to trade for the benefit of the beneficiaries. As with a non-trading trust, a trading trust separates legal ownership of assets from beneficial ownership and control. The controllers of the business are the owners and their family who exercise a controlling mind through their appointment as directors of the trustee company.

In article:

- What are Trading Trusts? Everything You Need to Know

- Trusts in Australia

- What is a trust?

- What is a trading trust?

- What other types of trust are there?

- What is a foundation and how is it distinct from a trust?

- Trusts and property settlement

- What is the typical structure of a trading trust for SMEs?

- What documents are required to form a trading trust?

- How do you set up a trading trust?

- General benefits/advantages of a trading trust

- Benefits of a trading trust for asset protection

- Potential disadvantages of trading trusts

- What risks do trading trusts present for creditors?

- What happens if the trading trust becomes insolvent?

- How might creditors protect their business from an insolvent trading trust?

- Are offshore trusts useful for asset protection?

- Conclusion

What are Trading Trusts? Everything You Need to Know

When thinking about the best legal arrangements and business form for your small or medium-sized enterprise (SME) in Australia, there are a few key matters that need to be taken into account, including:

- Managing your business tax liability;

- Protecting both business assets, and your own personal assets in the case of insolvency; and

- Ensuring that the right people have control over your business.

There are a range of business forms that might be used by a SME in Australia. including sole proprietorship, partnership, or a limited liability company. In this comprehensive guide we focus on another very common form of business set-up in Australia: the ‘trading trust’. Specifically, in this article we look at:

- The popularity of trusts in Australia generally;

- The definition of a trust;

- The various different forms of trust in Australia;

- The difference between trusts and foundations;

- Trusts and property settlement;

- The definition of a trading trust;

- The typical structure of a trading trust and who controls them; and

- Essential documents and steps required for set up.

We then turn to evaluating the pros and cons of using a trading trust including:

- General benefits;

- The benefit of trading trusts for asset protection;

- The disadvantages of trading trusts;

- Trusts and property settlement;

- The impact of insolvency on trading trusts and their creditors, and

- Offshore investment trusts.

Explanatory video on trading trusts (2020)

Watch Ben Sewell (Principal) break down trading trusts and their function in this brief explanatory video.

Trusts in Australia

Trusts are an extremely popular legal device in Australia. As there is no comprehensive, centralised register for trusts in Australia (in contrast to companies), we cannot know exactly how many are in existence. However, in 2015, it was estimated that there were 850,000 trusts in Australia. Furthermore, the Australian Tax Office (ATO) estimates that by 2022 there will be over 1 million trusts in Australia.

Trusts are not just popular in Australia. They feature prominently in the legal systems of many countries, but particularly in the United Kingdom and its former colonies. For example, as of 2020 it is estimated that there are 300,000 to 500,000 express trusts in existence in New Zealand (i.e. trusts explicitly created through a formal trust deed). With a population approximately one fifth of Australia’s, this suggests that trusts may be even more popular across the Tasman.

Trusts, or instruments like them, have been a popular tax minimisation and asset protection mechanism since medieval times. In their relatively modern form, they have been in existence since the passage of the English Statue of Uses (1536) 27 Statutes 294. For more information on the history of trusts, particularly in Australia read Lex Fullerton’s “The Common Law and Taxation of Trusts in Australia in the Twenty-First Century”.

Trusts, and in particular, trading trusts, are extremely popular in Australia with family-run SMEs. They are less suitable in Australia for larger businesses due to the concentration of control they provide for one person: the appointor. This is the individual who has the power to appoint and remove trustees.

What is a trust?

To understand what a trading trust is, we must first begin with the concept of the trust. A trust isn’t a legal person (like you, or me, or a company). Rather, a trust is a legal device by which one person holds property for the benefit of another person. The first person (the trustee) is under an equitable obligation to deal with the property for the benefit of the second person (the beneficiary). If the relationship is an express trust it will be governed by the terms of a trust deed. At law, there are three essential elements of an express trust:

- A trustee;

- Trust property; and

- A beneficiary.

Rather, than being a distinct ‘thing’, we might say that a trust is a ‘set of legal relationships’ between individuals called trustees and individuals called beneficiaries.

What is a trading trust?

A trading trust is a trust over goodwill and business assets with the trustee being the legal person responsible to creditors. A trading trust is usually a discretionary trust (more on what this means, below), whose trustee is a company, that is used to trade for the benefit of the beneficiaries. As with a non-trading trust, a trading trust separates legal ownership of assets from beneficial ownership and control. The controllers of the business are the owners and their family who exercise a controlling mind through their appointment as directors of the trustee company.

This means when you do business with a trust, you are actually only able to contract with the trustee and, if it is a trading trust, this is usually a $2 company. Therefore, by accepting, say, a credit application from a trading trust you are actually entering into a contract with the company that is the registered holder of the Australian Business Number (ABN) as trustee of the trust. This, of course, presents a range of risks to creditors which we discuss in significant detail further below.

What other types of trust are there?

Given the broad definition of a trust as a legal device, it is perhaps no surprise that this device is applied to various different areas of the law, and comes in many different forms. So far, we have mentioned that a trust may be:

- Trading or non-trading;

- Discretionary or fixed. In a discretionary trust, the trust property can be distributed at the discretion of the trustee or trustees. In a fixed trust the beneficial ownership of property is divided into units. The interest in trust property is then held absolutely by the unit holder. It is also possible to have a ‘hybrid’ trust which has both features.

Another important distinction in trusts depends on how the trust comes into being:

- Express or declared trusts. These occur when an individual (the ‘settlor’) establishes a trust on express terms in a trust deed;

- Presumed or implied trusts. These occur where there may not be express acts of the settlor to establish a trust, but the law presumes or implies that a trust is in effect;

- Constructive trusts. These are trusts imposed by the law courts in order to correct a void in the law that would otherwise exist and create an unconscionable outcome.

Our focus in this guide is on express trusts as these are the form that trading trusts take.

Other common applications of trusts include:

- Charitable trusts: If the trust has a charitable purpose it might be registered with the Australian Charities and Not-for-profits Commission. We discuss a related European concept, ‘the foundation’, in greater detail below;

- Foreign trusts. These trusts are managed outside Australia, but may hold Australian trust property and may have Australian beneficiaries. Under subsection 995 1(1) of the Income Tax Administration Act 1997 (Cth), they are trusts that are not a resident trust for Capital Gains Tax purposes. We discuss offshore trusts used for investment purposes at the end of this guide;

- Superannuation funds. In Australia, these funds must be held in the form of a trust: That is, the property is held to provide retirement or death benefits for members. These trusts must comply with the Superannuation Industry (Supervision) Act 993 (Cth) and related regulations;

- Testamentary trusts. These only take affect on the death of the testator;

- Bare trusts. These exist where the duties of the trustee have been completed but the trustee remains the legal owner (such as where trust property is simply awaiting being finally transferred to beneficiaries). We discuss these further in the context of trustee company insolvencies below;

- Trust accounts. Trust accounts, such as real estate escrow accounts or solicitor trust accounts hold money on behalf of beneficiaries. Recent reforms in Queensland alter the trust account framework for construction projects in Queensland to better ensure that construction funding is held on trust for subcontractors. For further discussion of applying trusts in the construction industry read the Australian Small Business and Family Enterprise Ombudsman’s Cascading deemed statutory trusts in the construction sector;

- Blind trusts. In this type of trust, the business interests of someone in public office are administered ‘blindly’ on their behalf to prevent the existence or appearance of a conflict of interest; and

- Family trusts. These are trusts created to benefit people who are related to each other. Often family trusts are themselves trading trusts (this is common, for example, with Australian family farms). To read more about the prevalence of trusts in family businesses in Australia see chapter 6 of the Parliamentary Joint Committee on Corporations and Financial Services report Family Businesses in Australia – different and significant: why they shouldn’t be overlooked.

What is a foundation and how is it distinct from a trust?

Trusts originate from the ‘common law’ legal system of the United Kingdom and have flourished there, as well as in countries and jurisdictions that were former UK colonies (such as Australia, Canada, the United States, New Zealand and Hong Kong). As the common law systems place significant emphasis on judicial precedent, and lines of cases interpreted in light of those precedents over centuries, it is little wonder that trusts law has become somewhat abstract and complex.

By contrast, in countries with a ‘civil law’ legal system, with comprehensive legal codes and less emphasis on precedent, trusts tend not to exist. But a concept with some similarities to trusts in those jurisdictions is known as a ‘foundation’. This is a specific legal form and not to be confused with what are sometimes called ‘foundations’ in Australia, but actually have the legal form of a charitable trusts. As with trusts, foundations are a very old legal mechanism. In Germany there are foundations that have been continuously in existence since 1509.

For example, German law permits the creation of a foundation for public or private purposes ‘compatible with the common good’. While the foundation may engage in commercial activity, this cannot be the main purposes of the organization. There is no minimum capital required (this can be contrasted with the most common business form in Germany, the ‘Gmbh’, which requires 25,000 Euros in initial capital). Foundations are a feature of state, rather than federal law.

If the foundation has a charitable purpose, it pays no taxes, except for the commercial activities they engage in. Foundations with private purposes pay tax just as a regular individual would.

As with trusts in Australia, foundations in Germany are a common ownership mechanism for corporations. For example, major appliance manufacturer Bosch, and international supermarket chains, Lidl and Aldi are owned by family foundations.

In the ‘Panama Papers’ scandal (for more information see the section on offshore trusts at the end of the guide), it was heavily reported that sham charitable foundations (such as ‘International Red Cross’ which had nothing to do with the actual Red Cross), had been used for tax avoidance purposes.

As well as in Germany, foundations are also popular in other European countries including the Netherlands, Sweden, and Portugal.

Trusts and property settlement

On the breakdown of a de facto relationship or marriage it is necessary to come to a property settlement in respect of the assets of the couple. In arriving at a pool of net marital property, all assets, and liabilities of both parties (yes, even debts – they’re not called STDs or ‘sexually-transmitted debts’ for nothing) must be placed together.

It is common, however, for parties to a marriage or de facto relationship to be either trustees or beneficiaries of family trusts and/or trading trusts. Many of these trusts also have the traditional trading trust structure whereby a limited liability company is the trustee. This raises the question, where assets are held in trusts (no matter what kind of trust that is), what happens on a post-breakdown property settlement?

Under the Family Law Act 1975 (Cth) the Court has extremely broad property altering powers. Under section 79(1), the court has the power to alter the interests in property of both parties. This means it has ‘trust-busting’ powers.

While the Court’s broad discretion in the Family Law Act 1975 (Cth) is not easily reducible to a ‘test’ for when trust assets may be ‘pulled out’ of that trust by the court, we can get a fairly clear idea of what the court emphasises by looking at some key cases.

In the High Court of Australia case of Kennon v Spry [2008] HCA 56, the court considered the extent to which assets in a discretionary trust could become part of the marital property pool.

In coming to its decision, the Court emphasised the degree of control that the husband had over the trust in that case. Under the trust deed, and all subsequent valid variations, the husband could vary the trust, appoint, and remove trustees, and put assets into the trust (which he did throughout the marriage). This combined with the wife’s status as a beneficiary (and her attendant right to due administration), were enough to qualify the trust assets as part of the net marital pool.

But the court will not always bust discretionary trusts. For example, in the recent case of Bernard v Bernard [2019] FamCA 421, the Court refused to consider a discretionary testamentary trust as part of the pool of marital assets for distribution.

In that case, the trust was settled by the husband’s father. There it was crucial to the Court’s decision that the assets came from the husband’s father’s estate, that the husband was not the settlor, and that he only had the basic interest as a beneficiary. In short, the husband did not exercise the requisite control. Therefore, it was separate property, not to be included in the pool of assets for property settlement.

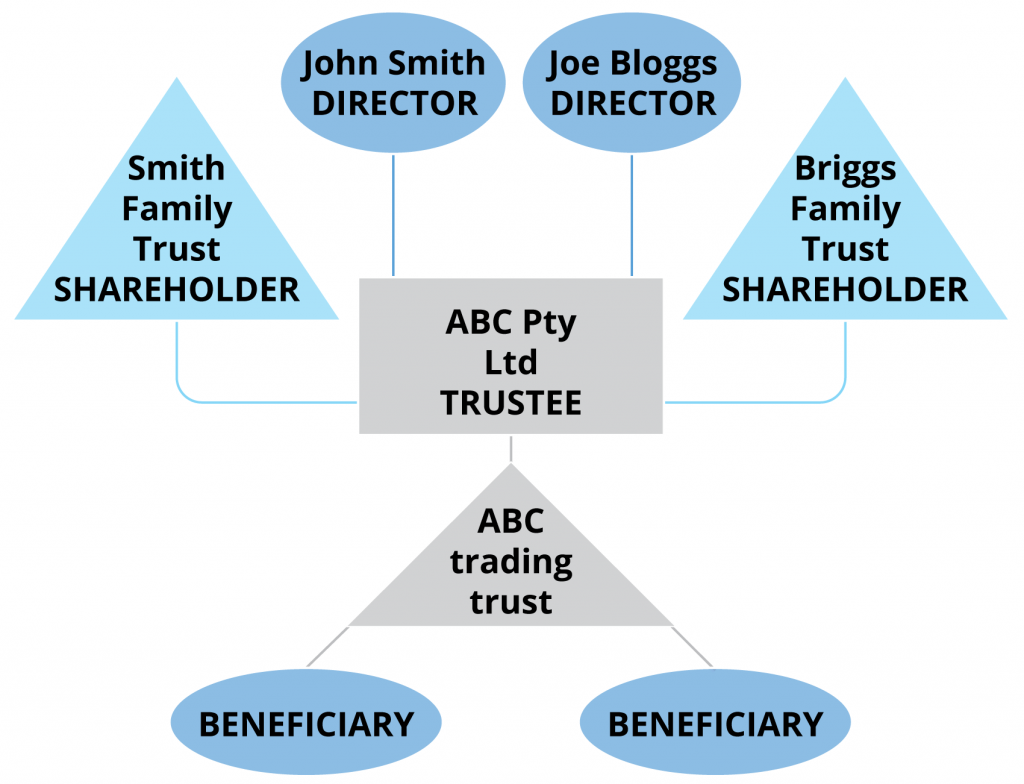

What is the typical structure of a trading trust for SMEs?

Trading trusts do not exist in a vacuum. They are typically combined with a set of other legal elements to create a potentially advantageous business structure for SMEs. For many SMEs, this will include their own personal assets being contained in a separate ‘family trust’. When setting up trading trust arrangements, it usually proceeds as follows:

- Two individuals decide to create a business together (the owners);

- They decide on a trustee structure. That is, they decide on how many trustees there will be and how many beneficiaries;

- They incorporate a company and call it, for example, ‘ABC Pty Ltd’. This company must be registered with the Australian Securities & Investments Commission (ASIC);

- A shareholding structure is determined. Once determined, shares are usually issued for a nominal value to the owner’s family trusts;

- Directorship structure: The owners both become directors of the trustee company;

- A trust is declared via a trust deed, and with an initial nominal working capital (e.g. $50);

- The working capital is loaned to the trading trust by the owners’ family trusts;

- Owners become the settlors and appointors of the trusts. That is, they establish the trust and can appoint or remove trustees; and

- The trust is usually a discretionary trust with decision-making required to be unanimous or in accordance with a shareholder’s agreement (bespoke).

Often, SMEs set up trading trusts using two distinct companies:

- One company is the trading company which holds the risk; and

- The second company becomes the trustee of the trading trust to hold title to assets.

The potential benefit of this arrangement is that no asset transfer is required upon insolvency –only the trading company is wound up, leaving the trust assets protected.

Of course, sophisticated creditors such as banks are aware of the potential risks that these arrangements present for them and will usually cross-collateralise any facilities.

Who controls a trading trust?

As a trading trust holds the assets of the enterprise, it is crucial to clarify from the beginning who has ultimate control of the trust:

- The appointor has ultimate control as they appoint and dismiss the trustees;

- The directors of the trustee company, unless replaced, control how assets are distributed. The trustee company, as trustee, has a host of equitable duties to the beneficiaries; and

- The beneficiaries have no control the trust. They would need a court order to end the trust.

What documents are required to form a trading trust?

A trust sets out relationships that are created through a trust deed, and this document may need to be evidenced in the future. The ATO or a liquidator may deem that a trust is not in existence if the documentation below cannot be evidenced when called upon. It is a good idea to have the trust documentation witnessed by a solicitor so that the solicitor keeps copies of the documentation on file for future reference.

The documentation required to establish the trust is:

- A company constitution for the trust company: The shelf company provider will include this document in the incorporation package with detailed instructions on adoption and execution;

- A trust deed: The trust deed must be signed and the settlor must also pay a nominal sum to the trustee (i.e. $50). Copies of the trust deed should be retained by the owners and this document may also need to be stamped for tax (depending on the place of domicile and the assets held); and

- Minutes of a meeting of the trustee company to accept the appointment as trustee: This will usually be provided by the shelf company but it may need to be bespoke (i.e. prepared by a solicitor).

It is advisable, but not essential, for persons participating in a trading trust business structure to enter into a comprehensive shareholders’ agreement (reminiscent of a partnership agreement) to cover matters not dealt with in the company constitution or various trust deeds, particularly in terms of planning for disputes, business failure, and trustee insolvency.

In addition, depending on the circumstances, the trading trust may need a loan agreement and general security agreement covering any loans that are made in the start up phase.

Note, there is also a need for ongoing separate documentation, such as tax returns under the company’s and the trustee’s tax numbers.

How do you set up a trading trust?

So, once you have decided to go down the path of setting up a trading trust for a SME, which steps should you take? We suggest:

- Set up a trustee company (utilising your professional adviser or a shelf company provider);

- Identify who will control the trust and be its appointor;

- Identify who will be the beneficiaries of the trust;

- Owners to seek advice from their respective tax accountants regarding streaming of trust distributions;

- Owners seek advice from their respective solicitors regarding specific items of the trust deed:

a) Amendments to right to indemnity

b) Exclusion of liability provisions

c) The scope of power of a trustee to sell assets

d) Powers of trustee to borrow monies

e) Whether owners can demand a say in management and profit distribution

f) The power of the appointors to replace the trustee - Owners to seek advice from their solicitors regarding whether a shareholders or quasi-partnership agreement is required;

- Settle and sign the trust deed;

- Pay stamp duty (where applicable);

- Apply for an Australian Business Number (ABN) and Tax File Number (TFN) for the trust as required by the ATO; and

- Open a bank account for trust operations.

Potential mistakes to avoid in set-up

When setting up a trading trust, there are a few common mistakes that should be avoided to reduce the risk of financial loss. These include:

- Setting up too many trustee companies and trust deeds. There should only be one trustee company (potentially two, if you are planning on using a holding company for the assets distinct from the training company), and one trust deed;

- Financial records of the trust should be prepared by a qualified accountant;

- The minutes of the trustee company meeting should be prepared by a solicitor;

- The trustee company should not conduct business separately to the trust because it may cause confusion about assets and income actually held in the trust;

- When land is purchased you should inform your solicitor that the company is a trustee so they can ensure proper declarations are made; and

- To minimise risk, husbands and wives should not both be company directors of the trustee company at the same time.

General benefits/advantages of a trading trust

Now that we have explained how trading trusts are set up and how they operate, it is necessary to explain why a trading trust may be a useful business structure for SMEs. So, what are the benefits or potential advantages of deploying a trading trust?

- It provides a level of asset protection. The trustee company may go insolvent while leaving the trust’s assets protected as the trustee company has no beneficial interest in those assets. We discuss this in more detail below;

- Limited liability through the corporate form of a trustee company. This means that the directors of the trustee company will not generally be liable for the debts of that company (though there will of course be a risk if the directors have personally guaranteed debts);

- The trustee has a right of indemnity over trust assets for expenses incurred in carrying out their duties. Note, however, the complications set out below in the context of insolvency;

- Tax treatment. The trust is not itself a taxable entity. While the trust must be registered with the ATO with a tax file number, the trustee/s submit tax returns in relation to the trust and taxation is limited (e.g. trustees must pay non-resident beneficiary withholding tax). Using a trading trust means that pre-tax income flows through the trust, and the trustee (in a discretionary trust) can distribute income between beneficiaries in order to ensure that tax liability is effectively managed. Each beneficiary is then taxed on their specific income. This can result in significant savings based upon the different marginal tax rates of beneficiaries;

- Flexibility to deal with changing circumstances, such as changing trustee or beneficiaries. The appointor has the ability to change these matters, in accordance with a trust deed; and

- Confidentiality of trading information. In general, there is less visibility of the activity of trusts that there is of ordinary corporation forms.

Benefits of a trading trust for asset protection

It is essential as a company director or business owner to design and implement personalised strategies to separate personal assets and wealth from business risks. In addition, it is important to implement measures designed to protect the assets of the business itself. Trading trusts may be one way of protecting the business’s assets.

The famous company law professor Harold Ford commented: “The fruit of the union of the law of trusts and the law of limited liability companies is a commercial monstrosity”. It is certainly true that the scope for frustrating creditors is considerable. The flipside, of course, of frustrating creditors, is the potential benefit it creates for the debtor trustee company and associated trading trust. As a business operated through a discretionary trust does not enjoy ‘separate legal entity’ status, the trustee company becomes liable for any business conduct and the trade debts are deemed to be the trustee’s own. Note also:

- There is no specific right for creditors of trusts to enforce judgments against trust assets because this may be frustrated by changing trustees;

- There is only a limited right of recourse against directors of trustee companies pursuant to section 197 of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth); and

- If the trustee company goes into liquidation then it is unlikely, unless there are substantial assets, that the liquidator will pursue proceedings against an incoming trustee.

To determine whether your current asset protection strategy for your trading trust is sufficient, you should make sure you are aware of and have accounted for the following matters:

- Unless excluded, trustees do maintain a ‘right of indemnity’ and an associated lien over trust assets to be able to settle debts incurred while lawfully conducting trust business. One consequence of this is that if the trustee company goes insolvent and liquidates, the liquidator may stand in place of the trustee and receive this indemnity;

- A trust deed may expressly exclude a right of indemnity against beneficiaries;

- Claw-back provisions: The Bankruptcy Act includes claw-back provisions which may operate to reverse pre-bankruptcy transactions (e.g. to spouses/family or superannuation);

- Personal guarantees: Do creditors have any personal guarantees for business debts? If directors of the trustee company have provided personal guarantees on debts, they can of course become liable;

- Discretionary trust provisions: Does the discretionary trust set up provide an alternative or management strategy in the case of bankruptcy of the appointor? Is the right to indemnity excluded by the trust deed?; and

- Loan security: Are loans from stakeholders appropriately secured? Have they been registered under the Personal Property Securities Act 2012 (Cth)?

Potential disadvantages of trading trusts

There are many potential benefits of trading trusts, including their usefulness for asset protection (though note the extensive limitations set out above). However, what are some of the disadvantages of using a trading trust?

- The tax advantages may be illusory for small-to-medium-sized enterprises because of trust administration costs. To ensure full compliance with trusts law, a range of requirements must be complied with (such as accounting and minutes requirements) which require engaging accountants and solicitors: These can substantially eat into tax savings.

- As discussed earlier, if there is a marriage or relationship breakdown, under the Family Law Act 1975, the courts have wide-ranging powers to ‘trust-bust’ and remove assets to add to the wider pool of marital assets.

- Disentangling a structure may be expensive and problematic.

- Beneficiaries can be liable for trustee debts. Consider the following cases:

- Hardoon v Belilios [1901] AC 118: Where a beneficiary gets all the benefit of the property, they should be liable to indemnify the trustee for loss;

- JW Broomhead (VIC) Pty Ltd v JW Broomhead Pty Ltd [1985] VR 891: Builder who traded through a fixed trust failed and beneficiaries were found to be liable for liabilities incurred;

- Mclean v Burns Philp Trustee Co Pty Ltd (1985) 2 NSWLR 623: A heavily geared trust was deliberately used to hide assets from creditors.

What risks do trading trusts present for creditors?

So far, we have been focused on the benefits, limitations, risks, and disadvantages for the debtors. What about the risks for creditors of a trading trust?

- There may be insufficient trust assets to pay all creditor debts, especially where the trust assets are held by a separate holding company;

- There may be a provision of the trust deed that excludes the scope of indemnity for all creditor claims. This may leave trust assets beyond the reach of creditors;

- The trustee may have breached the trust deed and lost its right of indemnity from trust assets. This means that as a creditor, there may be no assets to draw on to pay your debt from the trustees; and

- The directors of the trustee company may also be assetless and unable to pay out any claims that a liquidator makes against them. Where the owners of SMEs have made extensive use of trusts, including for protecting their own personal assets (such as their family home), this can blunt the effect of enforcing a personal guarantee against that director in the case of insolvency.

What happens if the trading trust becomes insolvent?

Recall that the trading trust is not itself a legal entity. This means that creditors enter into contracts with the trustee company, not the trust itself. If the trustee company is unable to pay its debts as they full due and payable, that company is insolvent and will generally enter into a formal insolvency process such as a liquidation or a voluntary administration. The liquidation process can either be voluntary, or a compulsory one imposed by the court. If the trustee company becomes insolvent and the liquidation process initiated, what does this mean for the debtor and the creditors?

As required by the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth), at the outset of the liquidation process, an insolvency practitioner known as a liquidator is appointed to oversee the process. The company stops trading and the liquidator takes over the reins from the directors (see section 474(1) of that Act). The first priority of the liquidator is to ascertain which assets are owned by the company in order to realise those assets and distribute any proceeds to creditors. Under section 477(1)(c) the liquidator has the power to sell or otherwise dispose of, in any manner, all or any part of the “property of the company”

Where the debtor company is a trustee company of a trading trust, this gets complicated. As the assets are held in trust, they are not, in the traditional sense, the property of the trustee company. While the trustee company is the legal owner of the assets, the equitable interest of the beneficiaries restricts the company’s dealings in that property. This means that the liquidator, acting for the trustee company, may be able to sell trust assets (if permitted by the trust deed), but it needs to be administered in the interests of beneficiaries, not general creditors.

Further compounding this difficulty, it is common for trust deeds to have ‘ejection seats’ for trustees in the case of insolvency of the trustee company: The trustee is automatically removed. In this case the liquidated corporate trustee becomes a ‘bare’ trustee. They still retain a right over trust assets; however, they do not necessarily have the right to sell those assets.

It is common for trust deeds to contain a right of indemnity for trustees for the costs of administering the trust. In addition, trustees usually have a ‘right of exoneration’ from the trust assets for any liabilities related to the insolvency. While this right of indemnity can be transferred to the liquidator, it does not automatically entail a right to sell trust assets.

Given the uncertainty in its powers to deal with trust assets, the liquidator would be wise to appoint a receiver, or apply to the court for the ability to sell those assets.

It is worth noting that there is always the possibility of the liquidator ‘piercing the corporate veil’ to go after directors of trustee companies personally for any wrongdoing.

Beware of Alter-Egos

Where the trustee is not at sufficient ‘arm’s length’ from the beneficiaries of the trust, there is a risk that the Court would treat the trust as an ‘alter ego’ of the trustee.

In In Re Richstar Enterprises Pty Ltd v Carey (No.6) (2006) FCA 814, Justice French stated:

“where a discretionary trust is controlled by a trustee who is in truth the alter ego of a beneficiary, then at the very least a contingent interest may be identified because… ‘it is as good as certain’ that the beneficiary will receive the benefits of distributions either of income or capital or both.”

In the case of insolvency, this means that depending on how the trust was set up, the liquidator may be able to successfully apply to the court for the appointment of a receiver to sell the trust assets.

How might creditors protect their business from an insolvent trading trust?

Given the difficulty creditors may have in recovering on debts owed to an insolvent trading trust, what should creditors do to protect themselves? We recommend the following:

- Carry out a credit check on the directors and the trustee company;

- Obtain a director’s personal guarantee from the beginning. This bypasses the difficulty of being able to access trust assets to pay the debt;

- Make sure your terms and conditions cover you. Read more about what to include in your credit agreements here;

- Establish a credit limit from the start;

- Watch out for Phoenix companies. These are companies that transfer their assets to another company for below market value before liquidating.

Are offshore trusts useful for asset protection?

So far, we have been focused on trusts in Australia, primarily trading trusts. However, many Australian businesspeople have found it attractive to consider offshore trust structures as a form of asset protection. In certain countries and jurisdictions commonly known as ‘offshore tax havens’, business structures are set up which may deploy trusts either alone or in combination with ‘shell’ companies. The perceived benefits of using an offshore trust include:

- Being taxed at much lower (to non-existent) tax rates in the offshore location;

- The limitation of potential legal actions against the trust in the offshore jurisdiction;

- Difficulties obtaining information about the trust by potential claimants; and

- The enhanced confidentiality that overseas jurisdictions can offer. For example, in some jurisdictions, company ownership can be held in ‘bearer shares’, where the owner is simply whoever holds the relevant document and does not need to be named.

There are significant risks in setting up such an offshore trust. The main risk is that the Australian resident will receive an Australian tax bill. A non-resident company controlled directly or indirectly by Australian residents will be deemed to be a “controlled foreign company” under Australian tax law. The secondary risk is that by entrusting assets to a foreign jurisdiction, the appointor will have more limited rights of recourse if they suffer civil or criminal misfeasance in the foreign jurisdiction.

Some popular types of asset protection trust available in offshore jurisdictions include:

- British Virgin Islands: VISTA protected trust (Virgin Island Special Trusts Act 2003)

- Cayman Islands: STAR trusts (Special Trusts (Alternative Regime) Law 1997)

- Labuan, Malaysian: Labuan special trust (Labuan Trust Act)

The ‘Panama Papers’ Scandal

The ‘Panama Papers’ was a 2016 data leak from a Panamanian corporate law firm involving 1.5 million leaked documents relating to 214,488 offshore entities. This data leak revealed extensive tax evasion and tax avoidance through the use of trusts, shell companies and other business structures.

In response to the Panama Papers, the ATO identified approximately 1,400 Australians in the released documents. Of those, 1,200 individuals were matched to their tax file numbers. In response, the ATO carried out a range of investigation and enforcement actions including sending 100 individuals notice that compliance action would be taken. The ATO also disclosed that they had recovered $50 million from 470 Australians in relation to the scandal.

In response to the Panama Papers scandal, international bodies such as the G20 and the OECD made a range of recommendations for improving transparency with respect to tax havens, especially with respect to trust devices. In the G20 High-Level Principles on Beneficial Ownership Transparency, countries committed to improving the transparency of beneficial interests in trusts. One of the recommendations was for a public listing of the identity of all beneficial owners. Australia reiterated its commitment to this at G20 meetings each year from 2015-2018. However, thus far, a register of beneficial interests has not been implemented by the government in Australia.

It is worth noting, however, that disclosure of beneficial interests is now a compliance requirement under money-laundering legislation when opening up bank accounts and carrying out certain other financial services activities.

What is interesting about Labuan special trusts for Australians (for both asset holders and creditors)?

While there are many different possible offshore locations where trusts could plausibly be used for asset protection and investment purposes, here we look at just one example, which is perhaps the closest to home for Australians.

This is a matter of interest for both asset holders and also claimants to interests in trusts settled in Labuan, Malaysia. This jurisdiction is a special zone for the purposes of tax and corporate law and is the subject of different law to the rest of Malaysia. The tax haven has crafted law to foster the investment of monies through trust structures. There are special tax rates so trust income is taxed at 3% of profit or at a relatively low flat rate.

Pertinent laws to protect Labuan trusts include:

- No foreign law or judgment in relation to marriage, succession or insolvency is enforceable against a Labuan trust;

- The onus of proof in any claim against a Labuan trust is generally “beyond reasonable doubt” (i.e. the criminal not the civil burden in Australia). This means it will be much harder to prove any claim against such a trust;

- A strict limitation period for commencement of court proceedings including one year from the date of any disposition;

- Successful claims against a trust may only be met from the property held by the trust (i.e. protecting the corporate veil); and

- Note that under Malaysian law an Australian judgment is not registrable under their express law of recognition.

The risks of offshore trusts

Perhaps the most significant risk with offshore trusts and related vehicles is that Australia has a system of worldwide taxation. This means that if you are a company or an individual that has a permanent place of residence, or a centre of control in Australia, you will be taxed in Australia. In addition, common reporting standards have made it easier for countries to share tax information with each other than ever before.

In Hong Kong, on the other hand, they have a territorial system of taxation which means that if you are in Hong Kong and you have income that arises or income that is derived from a non-Hong Kong source, you do not have to pay tax on it. In Ras al-Khaimah of the United Arab Emirates, you can live there completely tax-free. There is no corporate tax and no income tax but you do have to be a resident there to obtain this benefit.

Where someone wishes to stay in Australia and have a corporate headquarters somewhere else, you may be battling with the ATO. If you have no territorial link to Australia, then it would be a very attractive proposition for you to have your accounts set up in an offshore structure.

As a business, perhaps the only failsafe way to deal with any potential tax issues would be to sever ties with Australia. However, if you want to maintain ties with Australia, and have Australians who work for you, Australian clients, Australian operations, and so on, then that will be the challenge.

Historically, the ATO has not been as active as some other tax collectors around the world. For example, in the UK, the tax collection system has gotten to the point of going to cafes and counting the number of coffees that are made. In the past, the ATO has relied mostly on a passive approach but now relies more on a ‘data matching’ approach. The data matching approach means that they are trying to automate the way that they analyse and collect taxes.

Vanuatu used to operate as a tax haven, but it appears this has been shut down. Australian authorities have had difficulty retrieving information related to bank accounts and corporate affairs in places such as Vanuatu. However, there are a plethora of other jurisdictions in the Pacific such as the Cook Islands where you can do things such as set up your own insurance company, highlighting the fact that if one tax haven shuts down, then it is possible that two more havens will appear in its place.

The progress of Australia through the development of ABNs, GST and so on has made the use of the offshore world by SMEs more difficult. It’s notable that the Panama Papers did not reveal many Australians.

Conclusion

Trusts are an extremely versatile, and popular, legal device in Australia. They can be a useful mechanism for individuals in their own estate planning through:

- Distributing assets after death through a testamentary trust;

- Ensuring confidentiality for ownership interests (there is currently no register of beneficial ownership interests;

- Minimising tax liability.

But trusts are also an important business model in Australia through the device known as a trading trust. In a typical trading trust structure, business owners appoint a company as the trustee, and include themselves as beneficiaries of the trust to receive income at the discretion of the trustee company (a discretionary trust). A key perceived benefit of a trading trust for business is asset protection in the case of insolvency and eventual liquidation. The theory is that, as the assets are held in trust for beneficiaries, they cannot be accessed by the liquidator or creditors in the case of liquidation. However, this is not entirely true. It depends on:

- What the trust deed says. Is there indemnity for trustees out of trust assets? Is there an ipso facto ejection clause in the case of insolvency?

- The degree to which the beneficiaries are at genuinely at ‘arm’s length’ from the trustee company.

From a creditor’s perspective, it is essential to have arrangements in place, such as personal guarantees or personal property securities, to provide some degree of protection in the case of insolvency.

Finally, if considering an offshore trust, Australian businesses need to be extremely cautious due to the extensive tax jurisdiction of the Australian government.